By Phillip Orchard

Despite its enormous potential, India is by no means an inevitable counterweight to Chinese ambitions in the Indian Ocean. The country’s immense domestic needs and its preoccupation with land-based threats have prevented it from turning its attention fully to the maritime realm. And the more China races ahead with its breakneck military expansion, the harder it will be for India to catch up.

But it’s a mistake to look at Indian and Chinese maritime capabilities as an apples-to-apples comparison. India doesn’t need to match China destroyer for destroyer or missile for missile because India has some extraordinary geographic advantages in its favor – ones that also happen to make it particularly attractive as a partner with other powers in the region. And the strategically invaluable Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India’s great trump card in its intensifying competition with China, is moving into the spotlight.

India’s Point of View

For a country with more than 4,500 miles (7,200 kilometers) of coastline, India has never been particularly ambitious in the maritime sphere. This is, in part, because for much of its history it didn’t have much reason to be. Geographically, India is protected by the near-impenetrable Himalayas to its north, harsh subtropical regions to its east and deserts to the west. Its long coastline makes it vulnerable to seaborne threats, sure, but few powers have ever been capable of exploiting this vulnerability. Buffered by the vast waters of the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the open ocean, India is blessed with abundant strategic depth when it comes to naval threats. And at any rate, any invading power would confront India’s demographic immensity, which makes direct subjugation by force nearly impossible.

That outside powers have dominated the subcontinent in centuries past is a result mainly of its internal divisions. Its primary occupiers – various Muslim dynasties from the 11th century to the 18th century and the Europeans shortly thereafter – succeeded because they managed to turn India against itself, exploiting the competition among different factions and power centers to cultivate coalitions of collaborators who would support their largely commercial objections.

As a result, India has generally focused inward since it became independent. Its viability as a modern nation-state has depended on its governments’ ability to manage internal divisions. External geopolitics, with the exceptions of the periodic blowups with Pakistan and occasional border clashes with China, took a back seat to more immediate concerns. But the demands of this endeavor are changing, as is India’s broader strategic environment, forcing New Delhi to look increasingly to the far seas.

Its most vital lifelines flow from the west. To fuel growth and development, India’s economic interests have expanded far beyond the subcontinent. The country has well over a billion mouths to feed, and sustaining the level of economic growth and modernization necessary to support this population has given India a voracious appetite for commodity imports such as energy. In 2019, around 47 percent of the total energy India consumed came from imports, including more than 80 percent of its oil supplies. As a result, the country has been quickly expanding its naval presence around critical chokepoints near the Arabian Peninsula and Horn of Africa – waters known to be teeming with pirates, rebels and explosive risks rooted in Middle Eastern rivalries.

Indian interests in eastbound sea lanes are growing too as the country seeks to boost its status as a manufacturing and export power. Already, around 40 percent of India’s trade passes through the turbulent waters of the Strait of Malacca, which has plenty of pirates of its own – and, more concerning for India, Chinese ambition. As China moves to address its own strategic concerns to the east, secondary issues to its southwest are becoming more important, making India more of a potential threat, however unwittingly, and vice versa. China needs to find ways to bypass chokepoints in the East and South China seas, so it needs to build deep-water ports, pipelines and rail lines in India’s backyard. And to prepare for a potential conflict that blocks its maritime chokepoints, it also needs to develop naval forces to keep its backup outlets open and counter enemy forces coming from the west – an effort that will require a network of bases and logistics facilities on India’s periphery to support them.

Thus, India now has good reason to fear both Chinese encirclement and Chinese domination of more distant waters on which India increasingly relies. And this means India now has very good reason to invest considerably more in developing the capabilities to secure trade routes and sustain the regional balance of power with China.

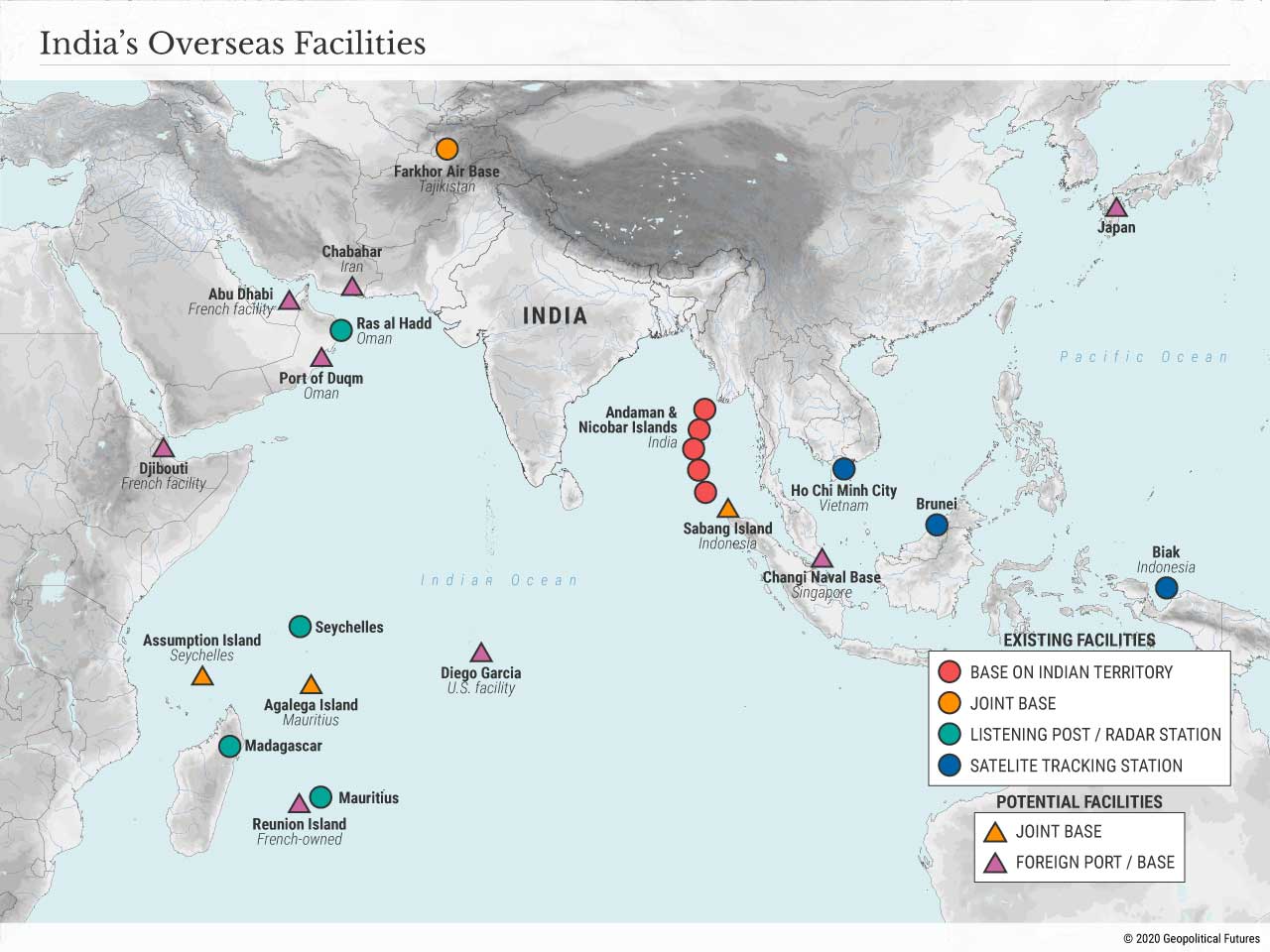

But India has had a hard time shifting resources from its army and air force to the navy. While it’s been touting grand plans for a 200-ship navy by 2027 (up from 130 today) and quietly laying the groundwork for its own “string of pearls” in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, the navy still received just 15 percent of last year’s budget, compared with 23 percent for the air force and 56 percent for the army (the bulk of which goes to pensions). The navy’s share of the pie is actually down from 18 percent in 2012. India’s struggle to shift focus to the maritime realm might be one motivator behind China’s moves in the Himalayas and with Pakistan. The more India stays bogged down in conflicts on land, in other words, the less it can shift focus to the sea.

The Metal Chain

China has little reason to fear India as a major threat to its interests in, say, the South China Sea or around Taiwan. But India doesn’t need to achieve military parity with China to become a problem. It simply needs to leverage its geographic advantages and the growing interest in cooperation from external powers like the U.S. This puts the spotlight squarely on the strategic godsend that are India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The archipelago, featuring some 572 islands (just 38 of them inhabited) stretches from just 100 miles north of the northern tip of Indonesia’s Sumatra island through the heart of the Andaman Sea toward Myanmar. The islands are, in effect, the gateway to the Strait of Malacca. In the view of Chinese defense planners, the more apt metaphor for the islands is a “metal chain.”

For India, developing the capabilities needed to threaten Chinese access to Malacca from the Indian mainland would be difficult and expensive, requiring rapid leaps forward in its submarine, aircraft carrier, air force and missile programs, as well as in India’s military logistics and surveillance capabilities. Threatening Chinese access to Malacca from the Andaman and Nicobars is more straightforward. The archipelago is the proverbial “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Indian bases there are ideally placed for conducting surveillance operations, deploying anti-ship missiles and radar stations, stationing supply depots, refueling fighter planes, and so forth.

The islands, moreover, make India immediately attractive as a partner for powers like the U.S. that already have the capabilities to maximize their strategic value – something that could allow India to keep China at bay without breaking the bank by trying to match China’s spending on the People’s Liberation Army. India’s growing ties with Australia are particularly notable in this regard, given how Australia’s Cocos Islands could play a similar role in blocking Chinese egress through the Sunda and Lombok straits. The Andaman and Nicobars also could facilitate deeper military cooperation with Southeast Asian countries that historically are leery of provoking China without the ability to defend themselves. In 2018, India and Indonesia reached a tentative reciprocal access agreement giving India access to a port on the Indonesian island of Sabang, located just southeast of the southernmost Andaman and Nicobar island.

India, though, is still in the early stages of modernizing the military infrastructure enough to maximize their strategic value. At present, the islands are home to seven air and naval bases. But India began a series of much-needed improvements – for example, lengthening runways to be able to handle fighter jets or long-range reconnaissance aircraft and expanding port infrastructure to handle large warships – only over the past few years. India has also been somewhat reluctant to open up the islands to foreign partners. Reciprocal access agreements it signed with the U.S., France, Japan and Singapore in recent years, for example, reportedly did not include the Andaman and Nicobars.

But there’s been a renewed sense of urgency in New Delhi to tap into the islands’ strategic potential more effectively. At the height of the crisis in the Himalayas last summer, there were several calls in Indian media to put the Andaman and Nicobars to work, and India subsequently held naval exercises around the islands to signal to China that aggression in the Himalayas could backfire in ways that could truly hurt China. In August, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi deemed the islands’ development a strategic priority and announced a new development plan. The same month, India announced the completion of a submarine optical fiber connectivity project in the area. In October, a U.S. long-range sub hunter became the first U.S. military aircraft to make a refueling pitstop. In December, India test-launched supersonic anti-ship Brahmos missiles from the islands. In March, Japan announced a $36 million grant for the development of energy storage systems on South Andaman.

Nothing will happen quickly. India’s budgetary problems remain, and the pandemic isn’t going to help. It’s leery of giving China any more reason to try to militarize one of its Belt and Road ports on India’s doorstep. There’s some evidence that Indonesia and, in particular, Malaysia aren’t exactly thrilled about the trajectory toward militarization of the Strait of Malacca, and India has an interest in handling Southeast Asian suspicions carefully. And India, in general, is still embracing the concept of strategic alignment with outside powers – something it historically has typically eschewed – only slowly.

Even so, on the question of whether and just how much India will emerge as a major player in the burgeoning competition over the Indo-Pacific, the Andaman and Nicobars are the center of gravity. Watch them closely.

No comments:

Post a Comment