Ben Richardson

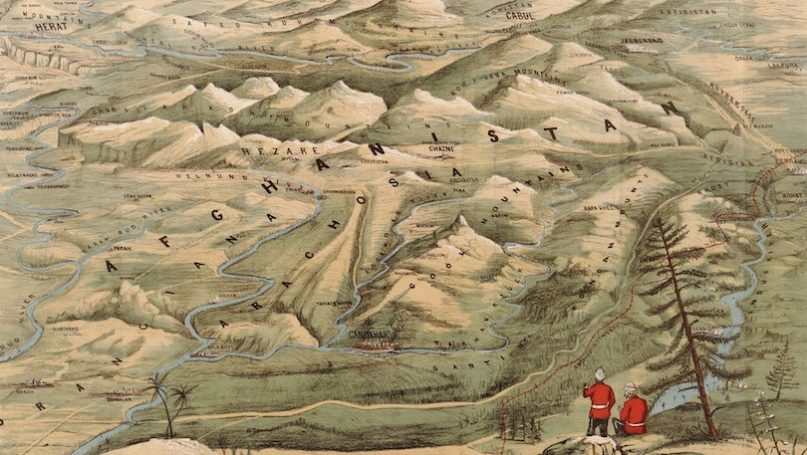

The disciplinary roots of International Relations are being subject to postcolonial inquiry. One intellectual figure who requires such scrutiny is Halford John Mackinder, a founding father of geopolitics. Mackinder’s ideas, now over a century old, still retain influence. Perhaps most notably, it was his 1904 paper ‘The Geographical Pivot of History’ about the strategic importance of Eurasia that was keenly cited by hawks defending the United States’ occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq. Like them, Mackinder also held imperial ambitions. His life’s work was dedicated to renewing the British Empire, which he feared would be overtaken by rival continental powers. True to his belief in the praxis of geographical knowledge and territorial statecraft, Mackinder also sought a career in politics. The first signs of this transition were in 1900 when he stood in the general election for a largely forgotten faction of the Liberal Party, the self-defined Liberal Imperialists. The story of his electoral misadventure helps illuminate the ideological context in which geopolitics emerged and the purposes to which it was put.

Mackinder began the new century as a man on the up. On 22 January 1900 he arrived triumphantly at the Royal Geographical Society to lecture on his ascent of Mount Kenya. Not only was he the first European to reach the summit, but the first to present his findings to the Society using colour photography. With its combination of national prestige and scientific advancement, the expedition fleshed out Mackinder’s reputation as a pioneering geographer. At this point he was known primarily for his scholarly contributions as principal of Reading College and reader at the Oxford School of Geography, both recently established thanks largely to his endeavours. During the spring he travelled around the country giving lectures on Mount Kenya and on 3 October – general election polling day – he was due to address incoming students at Reading Town Hall and receive scholarship applications for Oxford. But with just two weeks to go he tossed these plans aside and decided to stand for election himself in the midlands constituency of Warwick and Leamington.

The sudden decision was curious. Mackinder had no political sponsor at this time and no connection to the constituency save for some University Extension courses he had given at Leamington Town Hall a decade prior. It is possible that he was recommend to the local Liberal Association by J. Saxon Mills, a former master of Leamington College and their first choice to be candidate. Mills would have known of Mackinder from the University Extension movement and held similar views to him on questions of empire. But why enter the race so late? Maybe Mackinder sought distraction. Whilst receiving public adulation for his exploits in East Africa, in his private life he was going through a painful separation from his wife. All we know for certain is that the day he received the offer from the Liberal Association in Leamington, he immediately telegraphed back and set off to meet them that evening.

The general election of 1900 was a khaki election, so-called because it was dominated by military questions over the British annexation of the independent Boer states. Mackinder was unequivocal on this issue. He supported the Boer War and believed that any pacifist or anti-imperial sentiment had to be put aside so that Britain could remain a force for freedom. Keen to impress his position on the Liberal Association, Mackinder told them:

If we valued our British liberties we must be prepared to defend those liberties when the occasion arose, not only against small powers, but against great world powers, almost as great as ourselves. Therefore…it was impossible in such an age, whatever might be our wishes, to remain little Englanders. He was a Liberal Imperialist, but did not believe all wars were right, for war was a disaster at any time – (hear, hear) – but he would be no party to the omission of anything which should render it less easy for them to value their British liberties or to retain the power of extending those liberties.

This was a message he repeated throughout his campaign, urging the need for Britain to protect itself against the rapidly developing powers of Germany and the US through imperial federation with (white) Australia, Canada and South Africa: ‘a league of democracies, defended by a united Navy and an efficient army’. His bullish stance and renowned oratory evidently worried the opposition, so much so that the Unionist big gun Joseph Chamberlain made trips to Warwick and Leamington on the eve of the election to speak in favour of the incumbent. After introductory remarks in which Mackinder was branded a ‘mongrel’ due to his indefinable political breed, Chamberlain then ridiculed his misplaced allegiance, declaring that: ‘the only fault I find with Mr Mackinder is that he is not a member of our party… I hope that after this election he may see fit to join the Liberal Unionists’.

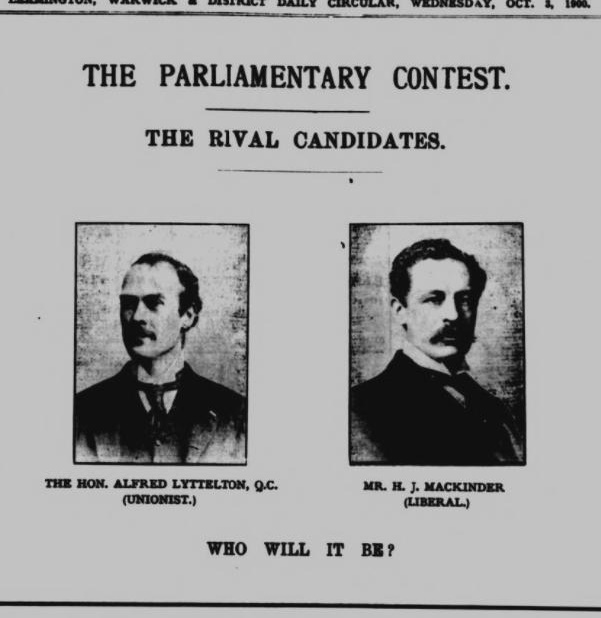

Newspaper image © The British Library Board. All rights reserved. Used with permission. With thanks to The British Newspaper Archive.

In the event, Mackinder’s case for Liberal Imperialism did not convince the electorate. Despite missing the entire election on government business in South Africa, his opponent Alfred Lyttelton increased his majority and won with 59 per cent of the vote. Somewhat conceitedly, Mackinder put this defeat down to poor organisation by the local Liberal Association, reminding them: ‘elections were not won by public meetings, however enthusiastic, or else they would have won’. Still, the Association recorded their thanks and saw him off with a chorus of ‘He’s a jolly good fellow’.

But Mackinder wasn’t finished yet. Three years later a by-election was called as Lyttelton had been promoted to Colonial Secretary and had to recontest his seat. The promotion came following the resignation of Joseph Chamberlain, who had controversially quit the cabinet to campaign for tariff reform. Mackinder was in full agreement with Chamberlain’s desire to make the British Empire a protected trade bloc. He joined the Tariff Reform League, and, fulfilling Chamberlain’s earlier hope, did indeed switch to the Unionists. He even offered to go to Leamington to speak in favour of his former opponent, which was, in his words, ‘the only manly course for me to adopt’. The reaction at the town’s Liberal Club was to take their photo of Mackinder down off the wall, shoot it to pieces, and burn what was left. Mackinder was advised not to travel to the town.

At least Lyttelton appreciated the offer. The following year, as Colonial Secretary, he presided over Mackinder’s illustrated lecture on the British Empire, which was intended for use in schools to cultivate patriotic imperial subjects. The project would come to fruition in the textbooks prepared for the Visual Instruction Committee of the Colonial Office, which Lyttelton encouraged colonial governors to adopt. The relationship between the two men was cemented at the 1906 general election when Mackinder again offered to speak for Lyttelton, as well as for Arthur Steel-Maitland, another tariff reformer, who was campaigning in the nearby Rugby constituency. This time the offer was taken up, but again it went down badly. As reported in the London Daily News, when Mackinder rose to speak at a public meeting in a Leamington school:

…it was the signal for a scene of deafening uproar, above which rose cries of “Mongrel”. He stood for five minutes smiling somewhat sardonically, and then, asking for a blackboard, wrote in chalk, “Be fair, as Englishman”. Again, taking his place on the platform, Mr Mackinder stood patiently awaiting an opportunity, which never came, to address the electors.

Undeterred, the two continued with their joint platform and the following day Mackinder made a lengthy speech in support of the Unionist position on tariff reform, which he described as ‘a life and death matter for the country’. Particular effort was made to discredit the Liberal Party claim that protectionist tariffs would lead to higher food prices, which Mackinder thought could be avoided by harnessing ‘the vast fields of Canada’ as a guaranteed supplier of cheap grain. The voters again disagreed and Lyttelton lost his seat in the Liberal landslide that swept aside the Conservative and Unionist alliance.

Mackinder finally made it into Parliament in 1910 as a Conservative and Unionist MP for the Glasgow constituency of Camlachie but by the early-1920s quit party politics entirely for a technocratic role chairing the Imperial Shipping Committee. He had become wary of the threat posed by representative democracy to expert rule and social order; a direct response to what he saw as the socialist indoctrination of workers by the Labour Party, but perhaps also a lingering bitterness to those first ego-bruising experiences in Warwick and Leamington. He also felt that in parliament he had done justice neither to his talent nor his cause, having never been brought into the inner-circle of government. At the end of his life he voiced regret that he ‘did not stick to Geography alone’. Maybe things would have turned out differently had he not rushed into politics, especially for a party he would later turn his back on. But then again, whoever heard of a cautious imperialist?

No comments:

Post a Comment