By SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG JR.

WASHINGTON: The Army’s drive for “decision dominance” through AI networks is not a repeat of the failed Future Combat System’s high-tech quest to “see first, shoot first,” the head of Army Futures Command says.

On FCS, Gen. Mike Murray said, the Army wrote a detailed wish list of performance requirements before it knew what was actually possible. Today, it’s diligently experimenting to see what’s possible with technology – technology that’s had more than a decade to advance since FCS was cancelled in 2009. Those advances should make it possible, military leaders say, to coordinate sensors, command posts, and weapons systems across land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace through an overarching Joint All-Domain Command & Control (JADC2) meta-network.

“We’re in the experimentation mode to understand what technology can and can’t do,” Murray told me and BD’s Theresa Hitchens in an exclusive interview. [Click here to read part I]. “I really do think that there are a lot of differences between the FCS experience and the path we’re on. [Today], I don’t think there is hubris. I think there’s actually humility.”

Or, as the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. James McConville, put it last week on a Brookings webcast: ““We don’t want to aim low – but we don’t want to aim too high either…. Where we are now, which is different than Future Combat Systems, is I think the technology is in a different place — and the things that we’re talking about are here already, the speed is there.”

When FCS was cancelled 11 years ago, Netflix still mailed you DVDs, self-driving cars were in their DARPA-funded infancy, and the iPhone was only two years old. Apple had just released the 3GS, whose high-end model boasted a whopping 32 gigabytes of memory: Today’s top-flight 12 Max Pro has 512 GB – sixteen times as much.

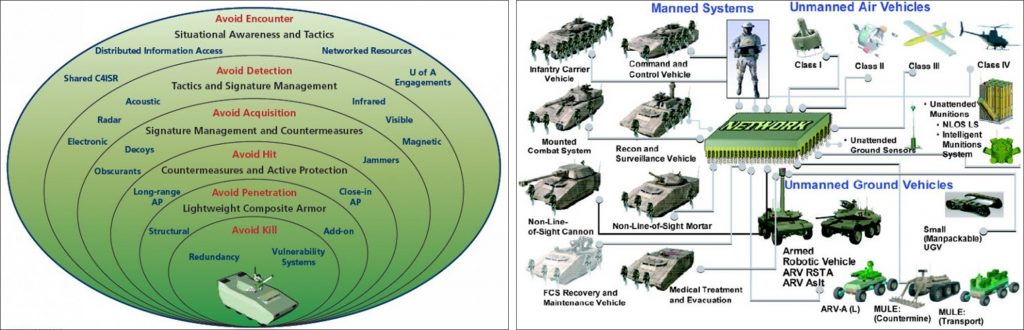

So it’s only reasonable to say technology’s evolved, particularly in the realm of sensors, networks, and artificial intelligence. But – as Army leaders have reminded us for years – the fundamental character of war itself remains the same: chaotic, brutal and ultimately intractable, defying all human efforts to bring clarity to what Clausewitz called fog and friction. The problem with FCS wasn’t just the specific technologies, a networked set of 18 interdependent sensors, robots, drones, and manned ground vehicles. It was the essential hubris of claiming that anything could allow you to consistently “see first, shoot first” – or as a later and more bureaucratic FCS formulation put it, “see first, understand first, act first, and finish decisively.” And “understand first” is the most hubristic part of that arrogant assertion.

The Army’s Future Combat Systems (FCS) program, cancelled in 2009, relied on sensors, networks, and superior information instead of heavy armor.

Yet the “see first, shoot first” catchphrase has resurfaced in some parts of the Army, to the alarm of at least one general. And now Gen. McConville and Gen. Murray have started talking about “decision dominance,” which depends on using technology — especially artificial intelligence – to process information faster and more accurately than the enemy, making faster and better decisions.

But that doesn’t imply some FCS-like high-tech infallibility, Murray told us in our interview. “I don’t think it will ever be perfect,” he said. “It just has to be better than our opponents are doing.”

And what if the enemy hacks and jams your network, taking away all your digital information? “That’s why we plan for the worst,” McConville told the Brooking webcast. “That’s why you have highly trained, disciplined, fit…and lethal forces that can operate when these systems do go down.”

“That’s all part of the Primary, Alternate, Contingency, Emergency-type plans that you build into your organizations,” McConville continued – a philosophy of quadruple-redundant backups known by the Army acronym PACE. “So if you have a system where everything is just working perfectly, [then] you’ve got tremendous overmatch, [but if] someone takes that down…that’s where you start to go to your backup plans.”

If the system works, however, it should allow the Army to take out targets faster and more accurately – and that’s at minimum. What Murray really hopes, he said, is that having better information from networked sensors, all helpfully organized for you by AI, could fundamentally improve military decision-making at every level, tactical to strategic.

“The decision dominance piece, Sydney, is much bigger than the targeting piece,” he said. “What we tried to do in Project Convergence 2020 and to a larger degree, what we’ll do in ’21 in terms of sensor to shooter work — I would argue that is only a very small part of decision dominance.”

The Army’s experimental “Origin” robot during Project Convergence

Most important is “the ability for a commander to make a good decision, not a perfect decision, faster than their opponent on a future battlefield,” Murray said. “I believe it is going to be an asymmetric advantage, because you’ve been around long enough to know the Military Decision Making Process and how long and laborious that can be.” (There’s an 118-page field manual on how to do the formal MDMP).

“That could be in a sensor-to-shooter scenario like we demonstrated” in the Project Convergence wargames last fall, Murray said. “Or] that could be, ‘what are my opponent’s tendencies in terms of their targeting priorities and their operational priorities?’ That could be, ‘what’s going on from a public sentiment standpoint?’”

“I hesitate to say that I know exactly where we’re going to end up,” Murray said. “So this is a journey to see what’s possible.”

“[Once] we understand the technology, we understand the integration challenges, we understand how to make these things work together, [then] let’s write the requirements document for what it is we’re going to build,” he said. FCS did it the other way around – and that, Murray argues, is ultimately why it failed. It’s a mistake he says the Army won’t make again.

No comments:

Post a Comment