by Patrick Wintour

Some will call it a tilt, others a rebalancing and yet others a pivot but, either way, the new big idea due to emerge from the government’s foreign and defence policy review on Tuesday will be the importance of the Indo-Pacific region – a British return east of Suez more than 50 years after the then defence secretary Denis Healey announced the UK’s cash-strapped retreat in 1968.

Boris Johnson and his admirals are billing the focus on a zone stretching through some of the world’s most vital seaways east from India to Japan and south from China to Australia as Britain stepping out in the world after 47 years locked in the EU’s protectionist cupboard. Others warn Johnson is indulging a hubristic and militarily dangerous imperial fantasy.

Either way, the British public are startlingly ill-prepared for what is to come. When the British Foreign Policy Group asked Brits whether they supported the UK’s greater involvement in the region, more than 50% said they did not know, or opposed the shift. This big idea is coming out of the blue.

At one level, the ignorance is natural. The UK – not on the Pacific Rim – has limited assets in the region. Diego Garcia is British owned but rented out to the Americans, a jungle training centre in Brunei exists, and there are some touchpoints such as Sembawang wharf in Singapore. Duqm port in Oman is being fashioned with UK money to receive aircraft carriers. It hardly amounts to a magnetic force.

Buccaneer jet bombers operating from HMS Victorious in the mid-1960s. Photograph: PA

Buccaneer jet bombers operating from HMS Victorious in the mid-1960s. Photograph: PABut the economic and political forces pulling Whitehall back to the region are real, and not all built on an imperial nostalgia. Many foreign ministries from France to Germany have recently produced Indo-Pacific strategies. Self-excluded from the European single market, the post-Brexit UK needs new trading waters in which to fish, while at the same time the rise of China requires the UK to give a more coherent response than the one offered by ministers so far.

The unspoken but understood purpose of Indo-Pacific as a foreign policy concept is for the maritime democracies to counter China and uphold the law of the sea. “The Indo-Pacific is a rallying call, a code for diluting and absorbing the power of Chinese power,” said Rory Medcalf, head of the National Security College at Australian National University and author of Indo-Pacific Empire.

For some, this makes the turn towards the Indo-Pacific truly compelling. “The single most geopolitical issue in the world today is the rise of China,” says Alexander Downer, the former Australian high commissioner to the UK. “Everything else pales into insignificance compared to that and for the UK to be a global player it has to accept that Indo-Pacific is the new geopolitical centre.

“It gets to the heart of how seriously the UK will be taken in the world. What has kept the peace since 1945 is the international rules-based system, and the UK is one of the countries that write those rules […] In the South China Sea there is a real issue of China trying to gain sovereignty through the use of international force and against the tide of international law. The UK needs to resist that. Maybe the UK will sell fewer Bentleys in Shanghai, but that is a fringe issue. This is an issue of war and peace.”

Downer had a big hand in the report A Very British Tilt, commissioned by the right-of-centre thinktank Policy Exchange, which stressed the importance of the region: it described its waterways, the Indian and Pacific Oceans, along with the inner seas and vast bays, as “the integrated pathways vital to the global economy, linking Europe and the western hemisphere with the world’s workshops.”

It said the region now accounts for close to half of global economic output and more than half the world’s population: it contains the world’s two most populous nations, China and India; the world’s second and third largest economies, China and Japan; the world’s largest democracy, India; and two of the world’s largest Muslim populations, in India and Indonesia. Its sea lanes are the “world’s most critical”, it said, including the Malacca Strait linking the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea.

The UK foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, endorsed that view on a visit to India in December 2020. “If you look at India and the Indo-Pacific region and take a long-term view, that is where the growth opportunities will be,” he said.

But what will a UK tilt to the region involve, and how is it best pitched?

The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, receives the British foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, in New Delhi. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, receives the British foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, in New Delhi. Photograph: Anadolu Agency/Getty ImagesSome, such as Prof Anatol Lieven, fear the UK is signing up to a US and largely military-led containment of China that, depending on how the policy debate in Washington evolves on issues such as Taiwan and the South China Sea, threatens to drag the UK towards economic disengagement from China. He says this could be a strategic mistake on a par with the Iraq war in 2003.

There won’t be a global Britain if we are not engaging with ChinaJo Johnson

Jo Johnson, the former universities minister and brother of the prime minister, is also appalled by the talk of confrontation with China or economic decoupling. “The reality is that if we follow a hard Brexit with Chexit, then global Britain is going to be an aeroplane that has dropped both engines,” he said.

“So I am very pleased the prime minister is describing himself as a Sinophile because he is facing a Conservative party for which Sinophobia is the new Euroscepticism. It’s the new political machismo, but it would be economic madness to decouple from China and incredibly destructive of this idea of global Britain, because there are many countries […] across the global south who are increasingly interdependent with China. There won’t be a global Britain if we are not engaging with China, and all the other countries enmeshed with it.”

But where does his brother stand in this debate? In his February speech at the Munich security conference, the first foreign policy speech afterthe UK exited its transition arrangements with the EU on 31 December, Johnson emphasised “the success of global Britain depends on the security of our homeland and the stability of the Euro-Atlantic area”, retaining Nato as the UK’s anchor. But he also suggested the UK was now looking east and the need to send a stern message to China.

He highlighted how the new UK aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth and accompanying fleet will deploy in May on a maiden voyage to the Indian Ocean coordinated with the US. “On her flight deck will be a squadron of F35 jets from the US Marine Corps,” he told the conference, “showing how the British and American armed forces can operate hand-in-glove – or plane-on-flightdeck – anywhere in the world.”

An RAF F-35B lightning jet preparing to take off from the flight deck of the HMS Queen Elizabeth at Portsmouth naval base. Photograph: LPhot Belinda Alker/MoD Crown Copyright/PA

An RAF F-35B lightning jet preparing to take off from the flight deck of the HMS Queen Elizabeth at Portsmouth naval base. Photograph: LPhot Belinda Alker/MoD Crown Copyright/PAEven though the carrier was ordered back in 2007 – when David Cameron, the Tory prime minister who succumbed to backbench pressure to call the Brexit referendum, was still opposition leader – the carrier is now being marketed by Johnson as the “embodiment of modern global Britain”. It is presented as a floating embassy, a source of force projection and protector of open trading routes. The first sea lord, Adm Tony Radakin, proudly told the Atlantic Council last month: “Britain is a carrier strike force again.”

Asked why its first mission is to the Indo-Pacific, Radakin stressed the importance of the region to the UK’s future. “If you take our departure from the EU as part of our stepping out into the world, it feels very normal that when we are looking for increased trade [and] increased prosperity, where might the UK show some global leadership and where might it enhance some of the links we have already got?” he said. “The Indo-Pacific is this incredible hub and so is somewhere the UK is looking to have a larger say in […] Where navies go, trade goes, and where trade goes, navies go.”

Radakin made no direct reference to China and even maintained the polite fiction that ministers had not yet decided if this strike force, including two Type 45 destroyers, an Astute Submarine and two Type 43s, would dare enter the international waters of South China Sea. This is not surprising. When a previous defence secretary, Gavin Williamson, in February 2019 announced HMS Elizabeth would travel to the South China Sea and be prepared to use lethal force to defend free and open waterways, China responded by withdrawing its invitation to the chancellor, Phillip Hammond, to visit for trade talks.

Radakin bridled at the suggestion that the UK was being unusually confrontational. “What is unusual is when the world starts to have a debate whether larger tracts of ocean are no longer accessible for other nations going about their lawful activity,” he said.

Construction at the disputed Spratley Islands in the south China Sea by China. Photograph: Armed Forces of the Philippines/EPA

Construction at the disputed Spratley Islands in the south China Sea by China. Photograph: Armed Forces of the Philippines/EPATom Sharpe, former naval commander and ex-Ministry of Defence spokesman, speculated on how China would respond when the fleet turned up. “I guarantee they will overfly the group with aircraft – that is a given. They will close and descend and they will test our responses. They will close the group with surface ships and there will be an exchange on various radios which is part of this business of cat and mouse.

“They will send their submarines out, perhaps there will be one waiting for us east of Suez as a nice surprise.” He warned of the risk of unclear messaging and miscalculation. With China, that can have dire real world implications, as Australia, now in the 10th month of a trade war with Beijing, has discovered.

“We have heard that the UK wants to uphold the international rules-based order. However, it’s not always clear what that entails,” said Veerle Nouwens, Indo-Pacific specialist at the defence thinktank Rusi. “To countries in the Indo-Pacific this can mean anything from working through regional multilateral organisations and capacity building, to naval exercises and freedom of navigation operations, or even some form of forward deployment in the region.

“Such activities weigh up differently in the perspectives of countries in the region. So signalling and communicating what the UK intends to do matters.”

Beijing is already bridling at the visit of the UK carrier group visit, especially since France and Germany are also deploying large warships to the region this year, with state media accusing the European powers of “contributing to the US anti-China stratagems”.

The Communist party-owned China Daily newspaper said that in posing as a defender of free waterways the UK may be hoping to provoke neutral countries in the region to side with the west against China, when in reality these countries do not want to be forced to pick sides in a great power struggle.

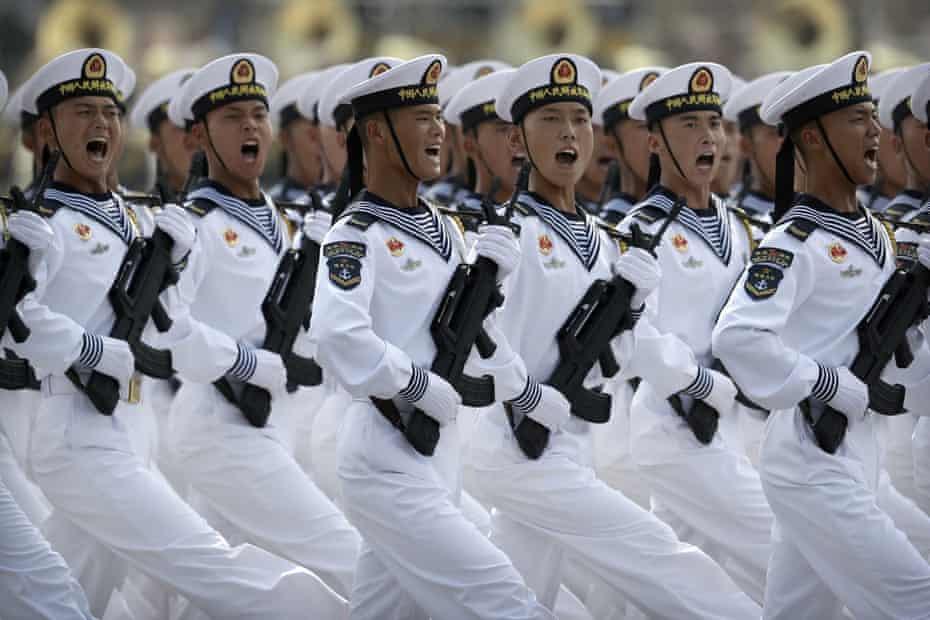

Soldiers from China’s People’s Liberation Army march during a parade in 2020 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the founding of Communist China in Beijing. Photograph: Mark Schiefelbein/AP

Soldiers from China’s People’s Liberation Army march during a parade in 2020 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the founding of Communist China in Beijing. Photograph: Mark Schiefelbein/APBeijing is also not happy that Johnson wants to turn the G7 into an alliance of 10 democracies by inviting South Korea, India and Australia. China also views as a threat any hint that the UK might join the quad, the growing security alliance between Japan, Australia the US and India, something Downer says may in reality be some years off.

That may require the prime minister, who in 2016 called the withdrawal from east of Suez a victory for the “retreatists and defeatists”, to contain himself.

“The British presence will be welcome, but it would be very easy for China to point to the British and French presence in the region as somehow harking back to colonial gunboat diplomacy,” Medcalf warns. “So the absolute imperative for Britain must be to do everything it does in partnership with regional countries. For Britain, the Indo-Pacific must be as canvas for cooperation with many partners rather than a place for imperial over-reach.” The UK, he suggests, should emphasise economic as much as military engagement.

Indeed the great prize in the UK’s Indo-Pacific strategy is access to expanding markets and membership of the 11-country Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) formed in 2018. This group, conceived as a regional counterweight to China, was salvaged out of the husk of the Trans-Pacific Partnership from which Donald Trump withdrew in 2017.

Looking at a map, it might seem odd that the UK wants to join this club. The international trade secretary, Liz Truss, is positively evangelical about a Pacific-based export-led recovery, however. She says it will give the UK access to a £9tn GDP and without any need to join a EU-style political club. Most of its existing members – accounting for a market of 500 million people and about 14% of the world economy – are enthusiastic, especially Japan, the UK’s lead ally in this enterprise and often described as the quiet leader of the Indo-Pacific. A preliminary decision is expected in May, with membership achieved early next year.

Liz Truss attends a signing ceremony with the Japanese foreign minister, Toshimitsu Motegi, on an economic partnership between Japan and Britain. Photograph: Kimimasa Mayama/AP

Liz Truss attends a signing ceremony with the Japanese foreign minister, Toshimitsu Motegi, on an economic partnership between Japan and Britain. Photograph: Kimimasa Mayama/APBut many UK trade experts, such as Ivan Rogers, the former UK ambassador to the EU, do not share Truss’s belief that the CPTPP is a gamechanger, let alone a substitute for the markets the UK removed itself from when it left the EU single market.

Elly Darkin, trade adviser at Global Council, points out the group’s share of UK trade in 2019 was around 8%, with four countries – Canada, Australia, Singapore and Japan – accounting for 86% of that. The UK already has free trade agreements with three of these countries, and hopes to wrap one up with Australia shortly. Darkin says the true benefit may lie in side agreements on issues like the digital economy and harmonising e-commerce, making it easier for companies to launch.

The other piece of the Truss jigsaw is a free trade deal with India, a holy grail that many trade negotiators have sought, and never found. Influential voices warn the UK off. “Good luck negotiating a free trade deal with India. It has not had a free trade deal with any third country since its foundation in 1947,” Rogers cautions. Narendra Modi’s policy Atmanirbhar Bharat (self-reliant India) is itself a form of protectionism.

The UK is doing all sorts of small things to ingratiate itself with India, however. It recently co-sponsored a UN motion that called out Pakistan’s failure to prevent the financing of terrorism. Johnson, as well as inviting Modi to the G7, hopes to go ahead with a cancelled India trip in the months ahead, where he will expand a recently agreed Anglo-Indian trade partnership, a precursor to a trade deal. British Eurosceptics such as Daniel Hannan see a trade deal as the way to make sure India self-defines as an English-speaking democracy rather than an Asian superpower.

But would the UK be prepared to give India and the other Asian tiger economies access to UK markets, as well as tens of thousands of visas?

Here the Indo-Pacific policy – with all its pretensions, fluidity and contradictions – reflects the deeper dilemma at the heart of the integrated review, and well captured by Jo Johnson.

“The government has got two really big ideas – the levelling-up agenda and the global Britain agenda – and the challenge to my mind is how the government can ensure they do not undermine each other but actually work together to support each other. There is clearly a potential for the levelling-up agenda, if it is seen to be couched in terms of helping communities that have been left behind or struggled in an era of globalisation, to undermine the other idea that the government is championing: free trade and the buccaneering deregulation.

“The tensions in the Conservative party about which dominates, whether it is the red wall MPs wanting heavy protectionism for communities that have been at the hard end of globalisation or our southern MPs who are all ready to support our free trading ambitions, is still is very real and yet to be resolved.”

... as you join us today from India, we have a small favour to ask. You’ve read

9 articles in the last year. And you’re not alone; through these turbulent and challenging times, millions rely on the Guardian for independent journalism that stands for truth and integrity. Readers chose to support us financially more than 1.5 million times in 2020, joining existing supporters in 180 countries.

For 2021, we commit to another year of high-impact reporting that can counter misinformation and offer an authoritative, trustworthy source of news for everyone. With no shareholders or billionaire owner, we set our own agenda and provide truth-seeking journalism that’s free from commercial and political influence. When it’s never mattered more, we can investigate and challenge without fear or favour.

Unlike many others, we have maintained our choice: to keep Guardian journalism open for all readers, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. We do this because we believe in information equality, where everyone deserves to read accurate news and thoughtful analysis. Greater numbers of people are staying well-informed on world events, and being inspired to take meaningful action.

In the last year alone, we offered readers a comprehensive, international perspective on critical events – from the Black Lives Matter protests, to the US presidential election, Brexit, and the ongoing pandemic. We enhanced our reputation for urgent, powerful reporting on the climate emergency, and made the decision to reject advertising from fossil fuel companies, divest from the oil and gas industries, and set a course to achieve net zero emissions by 2030.

No comments:

Post a Comment