BY AMY ERTAN AND TARAH WHEELER

In July, the U.S. and U.K. accused Russia of trying to steal vaccine research. Russia and North Korea have targeted vaccine production facilities, attempting to steal information. This was the first in a number of publicly disclosed cyber-enabled attacks—some carried out by nation states, some not—on vaccine research, production, and distribution facilities. In October, cyber criminals reportedly caused a shutdown of global manufacturing systems of a laboratory that had just received permission to manufacture Russia’s Sputnik vaccine. The Solarwinds attack targeted the U.S. National Institutes of Health, while Russian criminal groups continue to launch attacks on U.S. hospitals. The recent Hafnium Windows server exploit also targeted the U.K.’s National Health Services.

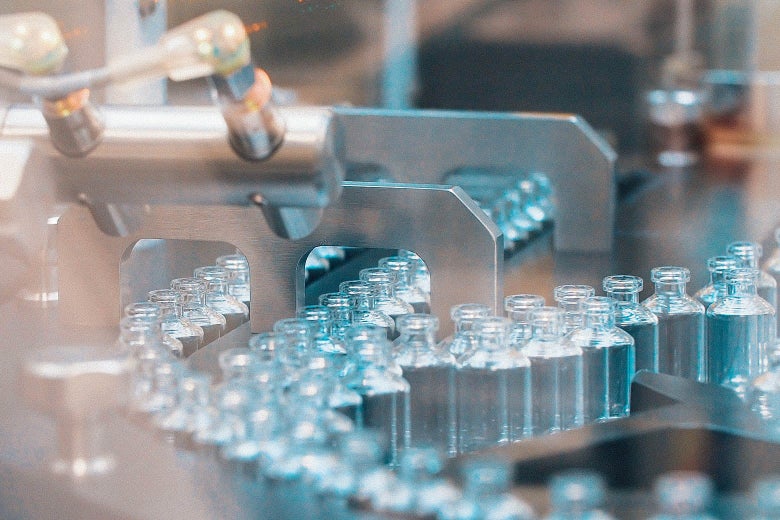

Vaccine information is a poorly guarded treasure for malicious interference and foreign espionage, and the attacks we see on the news are the ones we know about. The true number of malicious attacks will be significantly higher. It might seem that stealing vaccine research isn’t a big deal: After all, we want everyone to get vaccinated, so why not share the information? But once someone has access to steal the vaccine, they have the access to do anything they want. It is not as if cyber criminals are going to steal all vaccine production research and spin up functional vaccine facilities elsewhere—and if they did, we’re not sure we’d even care. More vaccine is better. These criminals are trying to disrupt production, not counterfeit it. That leads to less vaccine and more deaths. The vulnerable vaccine supply chain is in desperate need of better security.

The COVID-19 vaccine supply chain consists of the global research, production, storage, and distribution operations around the world. Most of the companies involved in the vaccine supply chain use a narrow range of software and information technology solutions from global providers like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. That means a cyber exploit that works on one company is extremely likely to be applicable in another. As the recent Microsoft Exchange Server attack illustrates, when everyone uses the same tools, we are all vulnerable to the same series of exploits.

In the normal course of medical developments, doctors and medical institutions solve challenges to public health by publishing their findings and collaborating on technical challenges, while still managing to keep their intellectual property safe.

But that isn’t happening in the pandemic. In the overheated and sped-up vaccine production timeline, vaccine companies are afraid they’ll lose intellectual property or experience negative publicity. We now know that vaccine supply companies are not solving the infosec information gap and sharing information as rapidly as they should. Two different Indian vaccine companies hit with the same attack are unwilling to share cybersecurity information with each other and appear to be fighting regulatory attempts to investigate. Police and regulators are finding it almost impossible to get information from Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, another hacked India-based company unwilling to share the details of its recent attack.

The only global organization with the power to drive a solution to this problem is the World Health Organization. WHO can start by publicly censuring vaccine supply chain companies that do not share information about cyberattacks with other companies, including competitors. There is no international mechanism yet to mandate this coordination, but WHO can use its international position to drive public accountability. It’s done so in the past when law or convention has broken down in issues of global public health. For example, WHO has made statements of censure condemning “virginity tests” and attacks on medical facilities in Libya. WHO statements are hosted publicly on its website and include calls on governments to appropriate manage access to medicines, and stern reminders on member party commitments on tobacco. When it comes to information security WHO has signed joint statements around data privacy and COVID-19, and issued guidance on privacy and contacts tracing.

It’s difficult to add up the weight of international disapproval to determine its actual effects, but, together, WHO statements of censure (which hold moral weight given their purpose in international health response) and powers to urge information sharing could drive cooperation across the vaccine supply chain. This is better than doing nothing and helps raise awareness of and stem the security gap while long-term solutions are developed.

If a company making vaccines gets attacked, that is not necessarily its fault. If another company, even a competitor in the supply chain, is subsequently attacked using the same exploit techniques, it could absolutely be the responsibility of that first company. If its knowledge could have prevented the attack, its inaction deserves the condemnation of the international community. When it comes to vaccines, no company should risk global health for the sake of pride, profit, or brand management. The World Health Organization can use its unique standing as the global coordinator of health information and its position as a moral authority to strongly encourage information security collaboration that can save lives.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

No comments:

Post a Comment