By Commander Michael Dahm, U.S. Navy (Retired)

THE 1991 GULF WAR was a harbinger of change for the Chinese military. In just 42 days, a United States–led coalition eviscerated the Iraqi military and expelled it from Kuwait. Before Operation Desert Storm, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was aware of its shortcomings relative to the West, but the war underscored the magnitude of the problem. The similarities between the PLA and the vanquished Iraqi military—an army-centric force organized for a defensive campaign—created a sense of urgency, as Beijing realized its military was ill-prepared to face a modern foe like the United States. The transformations in Chinese military strategy, technology, and force structure born out of the Gulf War have been seismic, shifting the balance of power in East Asia and portending global challenges for the U.S. military.

THE 1991 GULF WAR was a harbinger of change for the Chinese military. In just 42 days, a United States–led coalition eviscerated the Iraqi military and expelled it from Kuwait. Before Operation Desert Storm, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was aware of its shortcomings relative to the West, but the war underscored the magnitude of the problem. The similarities between the PLA and the vanquished Iraqi military—an army-centric force organized for a defensive campaign—created a sense of urgency, as Beijing realized its military was ill-prepared to face a modern foe like the United States. The transformations in Chinese military strategy, technology, and force structure born out of the Gulf War have been seismic, shifting the balance of power in East Asia and portending global challenges for the U.S. military.The 30th anniversary of the Gulf War is an appropriate time to examine where the PLA was three decades ago and what it may become. Chinese President Xi Jinping recently set a goal for the PLA to become a “world class military” by 2049, the centennial of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. What the U.S. military accomplished in Operation Desert Storm certainly represents a world-class standard in terms of joint force, expeditionary operations. Well before Xi’s edict to achieve this status, however, China understood its military needed a complete overhaul to achieve three outcomes: a joint force featuring a substantially improved air force and navy; precision-strike capabilities; and a modern command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) system. As impossible as those lofty goals may have seemed in 1991, in just a few decades, the PLA has made stunning progress toward them.

Chinese researchers have referred to the Gulf War as the “epitome” of information warfare.1 Alongside stealth, precision-strike, and joint operational capabilities, the war showcased psychological operations, electronic warfare, and computer network operations. PLA lessons learned from the Gulf War led almost inevitably to China’s 2004 shift in military strategy toward “informationized warfare”—warfare transformed by information—which is still the prevailing form of war that drives PLA force structure and strategy. Informationization and information-control are not a Chinese sideshow, they are central to PLA operational concepts and campaign design.2

The Gulf with Wars Past

Until the Gulf War, Chinese military strategies had been based on a “People’s War” concept—a total war, counterinvasion approach that emphasized large ground formations and national mobilization. Potential strategic adversaries included the United States (following the Korean War) and Soviet forces arrayed along China’s northern border since the 1960s. China’s 1979–91 conflict with Vietnam also primed the PLA for a shift in military strategy. The four-week-long 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War is often mistakenly cited as the PLA’s most recent combat experience. Despite Beijing declaring victory in its punitive campaign against Vietnam in March 1979, border clashes continued for more than a decade. PLA forces from across China rotated through its southern frontier well into the 1980s; millions of artillery rounds were exchanged; thousands died on both sides. The conflict culminated in 1988, with China’s seizure of Vietnamese-claimed reefs in the South China Sea that later would be built into massive artificial islands.3

Other developments also served as catalysts for changes to PLA strategy in the 1990s. China’s strategic nuclear deterrent reduced the chances of a large-scale foreign invasion. Following the Soviet Union’s decline in the late 1980s, China’s threat axis pivoted away from its northern border. Attention shifted to the possibility of conflict over Taiwan independence and the threat of U.S. intervention.

The 1991 “highway of death” in Kuwait—on which U.S. combined arms destroyed between 1,000 and 3,000 Iraqi Russian- and Chinese-made tanks, armored personnel carriers, trucks, and other vehicles—vividly illustrated for China that its aging military equipment was no match for Western technology. U.S. Marine Corps

But based largely on lessons from the Gulf War, China’s Central Military Commission issued new Military Strategic Guidelines in 1993 that represented a wholesale reevaluation of PLA strategy. While the PLA had been intently studying conflicts such as the Arab-Israeli wars and the Falklands War, in the minds of PLA scholars, the Gulf War heralded a profound shift in the character of modern warfare. Regional wars fought with modern weaponry were identified in the new Chinese strategy as “local wars under high-technology conditions.” However, in the 1990s, the Chinese military had little in the way of high technology to deal with what it had just witnessed in Iraq.

The Post–Gulf War State of the PLA

Given the PLA’s status as a “near-peer competitor” of the U.S. military today, the backwardness of China’s military in 1991 is striking. Even Chinese assessments put the PLA 30 to 40 years behind Western militaries. Most Chinese equipment at the time was based on 1960s-era Soviet technology. In the 1980s, Chinese defense industries were known for producing large volumes of low-tech Soviet knock-offs that were sold across the developing world. The Iran-Iraq War (1980–88) had been particularly lucrative. China supplied more than $7 billion in arms to Iraq and Iran, some of which Iraqi forces employed during the Gulf War, but with little effect.4

The PLA had a decidedly “brown-water” navy in 1991. The PLA Navy (PLAN) consisted of hundreds of patrol boats and a handful of destroyers and frigates based on 1950s Soviet designs. Chinese shipyards built dozens of antiquated diesel-electric submarines and a small number of noisy, indigenously produced nuclear-powered submarines. Virtually all PLA Air Force (PLAAF) aircraft were copies of Soviet MiG-19s and MiG-21s. A Chinese version of the Soviet SA-2 surface-to-air missile provided what passed for strategic air defense. PLA ground forces were built around antiquated Soviet-designed armor and were only beginning to experiment with combined-arms operations. PLAN marines offered few expeditionary capabilities.

Any advanced military technology found in China in 1991 had likely come from the West. Near the end of the Cold War, the United States and Western Europe sold military technology to the PLA as an “enemy-of-my-enemy” hedge against the Soviets. In 1985, the United States supplied China with 24 Sikorsky S-70/H-60 Blackhawk helicopters. Other helicopters were French designs. China’s YJ-8 antiship cruise missile bore a strong resemblance to France’s Exocet.5 A late-1980s U.S. initiative proposed outfitting 50 Chinese J-8 air-superiority fighters with advanced avionics, including the F-16 AN/APG-66 radar.

Most Western arms sales were suspended in June 1989, however, when the PLA violently put down protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square. The Chinese kept what they had acquired pre-sanctions, of course, including Western technology to outfit a Type 052 Luhu-class destroyer commissioned in 1994—U.S. gas turbines, German diesel engines, French sonar and electronics, and an Italian torpedo system. Interestingly, the United States issued a waiver from the Tiananmen sanctions to continue the J-8 upgrades. However, $200 million in U.S. defense contractor cost overruns achieved what international condemnation of the PLA could not. Beijing unilaterally canceled the so-called Peace Pearl contract in 1990.6 The PLA would need to look elsewhere for 21st-century military technology.

PLA Leapfrog Development

In applying lessons from the Gulf War, the PLA focused on developing joint capabilities, which necessarily meant drawing down its two-million-man army while building up a technologically advanced navy and air force. The PLA also realized that it required significant long-range precision-strike capabilities to enable greater defense in depth and to support offensive operations. To locate enemy targets and coordinate the joint force, the Gulf War demonstrated that the PLA required robust, survivable C4ISR networks.

Acquiring high-technology platforms, weapons, and C4ISR became an urgent priority, and China’s defense industrial base in the early 1990s was not up to the task of originating such equipment. Indigenous Chinese design is not how the PLA first evolved following the Gulf War. China instead pursued a strategy to reverse engineer technology acquired from foreign sources, principally from a defanged and cash-strapped Russia. Overt arms purchases from Russian, European, and Israeli sources were supplemented by aggressive covert actions to acquire military technology from the United States and elsewhere.7

Well into the 2000s, Chinese research and development was directed not at inventing, but instead on integrating and improving acquired technologies, in a strategy referred to as “leapfrog development.” China continues to capitalize on its lagging position in many areas, acquiring foreign technology to advance its standing in cutting-edge fields such as artificial intelligence.8 Still, there is no doubt that China’s defense industries have made significant and demonstrable progress in some high-technology fields in recent years—space and missile technologies stand out as examples.

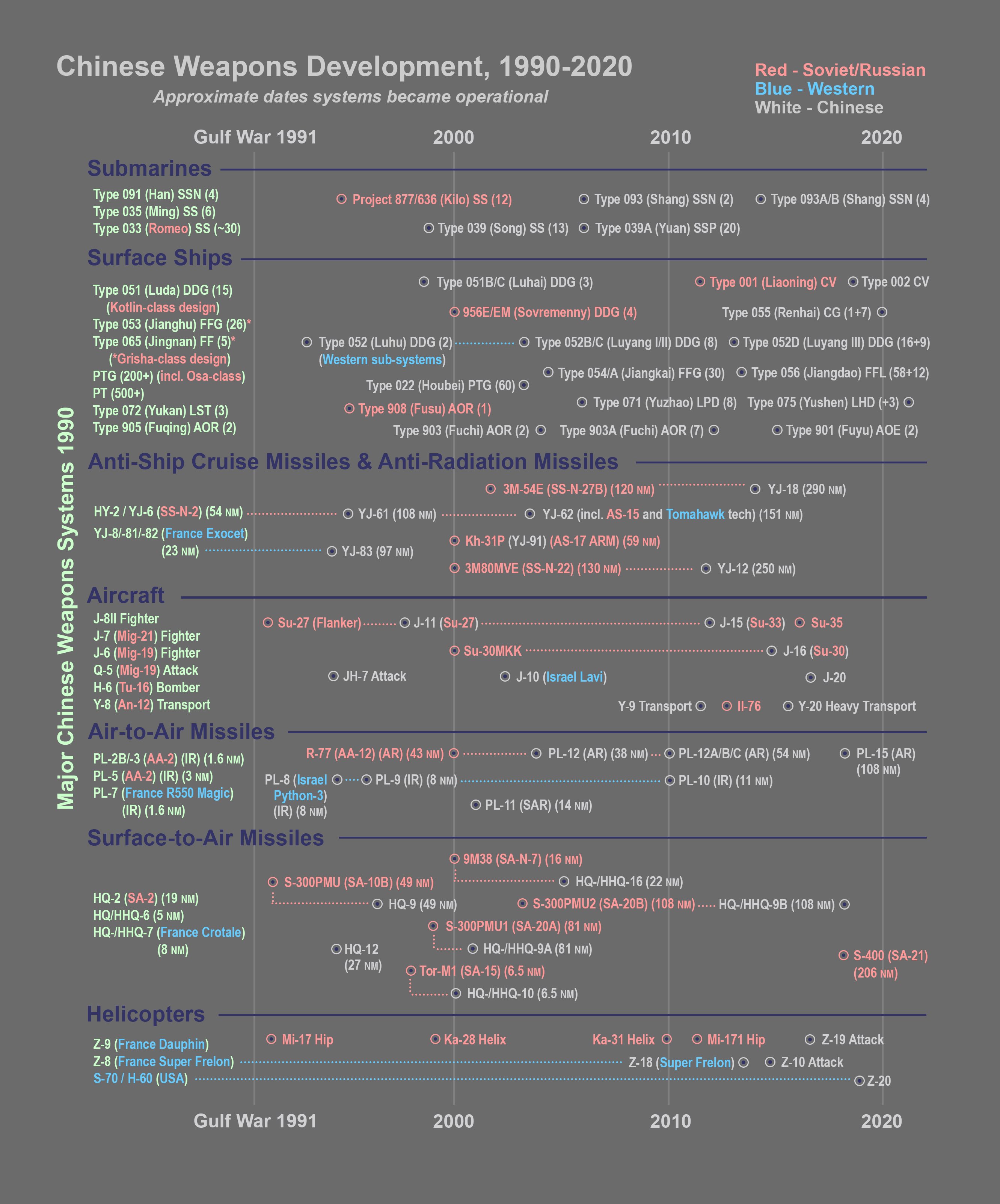

The tables below—Chinese Weapons Development, 1990–2020—depict when different military systems were acquired by the PLA and the technological leaps in Chinese manufacturing that followed, showing how many major Chinese systems trace their lineages to foreign acquisitions.9 Foreign military systems acquired in the 1990s significantly improved PLA capabilities. In the 30 years since the Gulf War, PLA innovation has been all about adaptation and improvement, with little in the way of originality.

Naval acquisitions in the 1990s and early 2000s included four Russian Sovremenny-class destroyers and 12 Kilo-class diesel-electric attack submarines. The purchases offered a trove of weapons, electronics, and propulsion technology to improve indigenous Chinese development. PLAN leaders had been impressed by the U.S. Navy’s “high-speed mobility and multidimensional combat capability” supporting air and ground operations in the Gulf War.10 In 1992, eager to emulate aircraft carrier battle groups, the PLAN initiated discussions to purchase an unfinished Soviet aircraft carrier (the Varyag, an Admiral Kuznetsov–class carrier built in Ukraine).11 Following a painful and expensive refit in China, the ship eventually was commissioned as the Type 001 aircraft carrier Liaoning in 2012. China’s burgeoning commercial shipyards have produced a number of PLAN ship classes, especially smaller patrol boats and corvettes.12 China commissioned more than 300 ships and submarines between 2000 and 2020, making the PLAN the world’s largest navy.

While in recent years China has revealed ostensibly unique designs, such as the stealthy J-20 fighter, most PLAAF aircraft have decidedly Russian origins. There also is evidence of Israeli involvement in the development of China’s first “indigenous” fourth-generation fighter, the J-10, which bears a striking resemblance to Israel’s Lavi fighter.13 China continues to incorporate high-tech Russian and European components into its aircraft and missiles.14It still purchases, integrates, and exploits cutting-edge equipment, such as Russia’s Su-35 fighter and S-400/SA-21 surface-to-air missile system—to say nothing of technology stolen from Western defense contractors in cyber hacks that continue to be a staple of PLA development.15

Precision-Strike with Gulf War Characteristics

The Gulf War highlighted another Chinese requirement: long-range precision-strike capabilities. These enable what the PLA calls “noncontact warfare.” Noncontact warfare does not mean “nonkinetic.” Instead, it refers to warfare in which enemy forces are not in direct contact. Chinese cruise missile programs may have received benefits from the first use of U.S. Navy Tomahawk land-attack cruise missiles during the Gulf War. Tomahawks that failed to reach their targets were rumored to have been harvested from crash sites in Iraq and reverse-engineered into Chinese cruise-missile designs. In subsequent years, China almost certainly obtained updated Tomahawk technology from missiles fired into Afghanistan that fell short and crashed in Pakistan during Operation Enduring Freedom.16

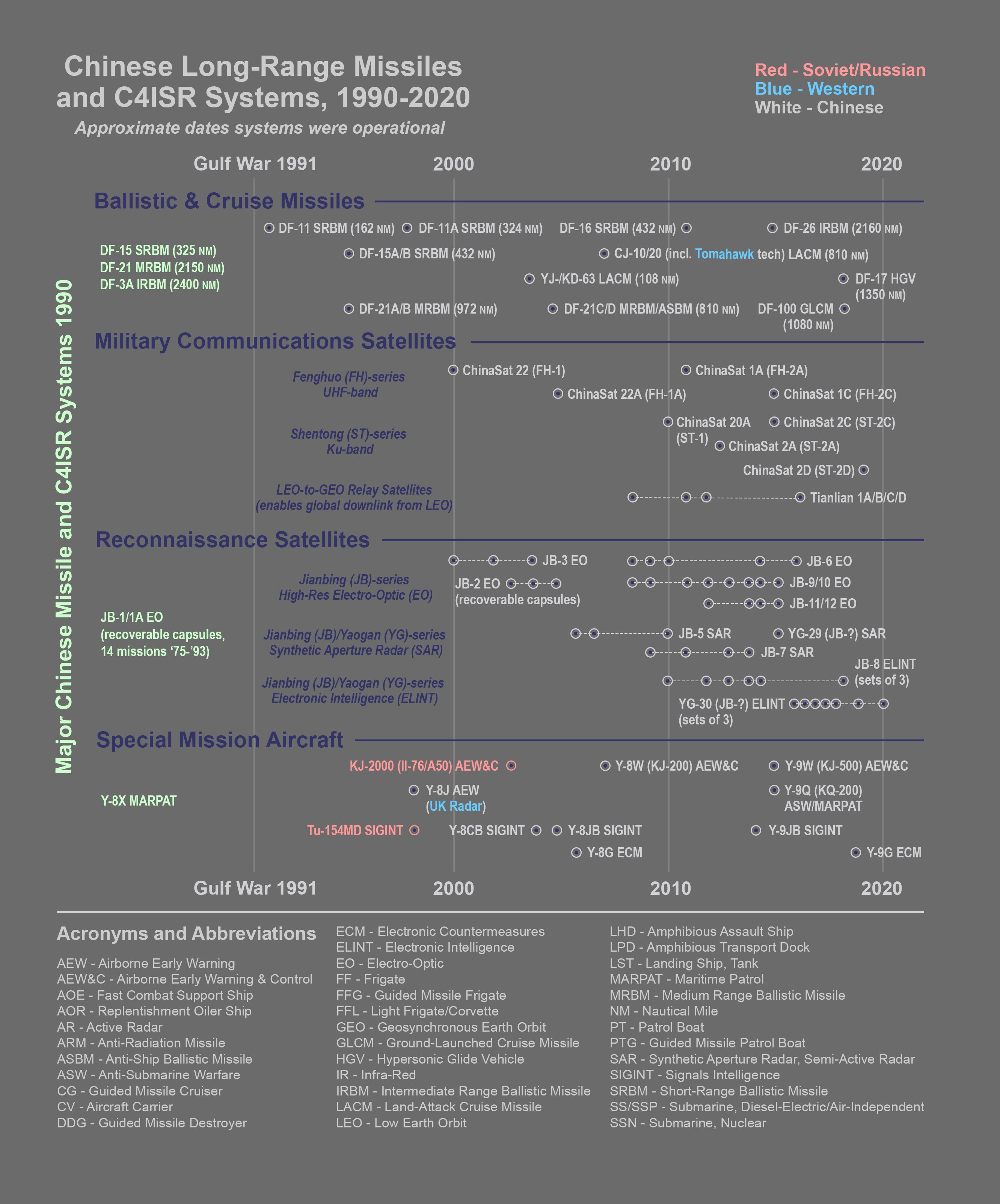

China has pursued independent development of ballistic-missile technology and has excelled in that field. However, in 1991, the PLA had just three types of conventional ballistic missiles. Subsequent generations of a variety of Chinese ballistic missiles have featured significantly increased accuracy using satellite navigation, active and passive seekers to enable maneuvering reentry vehicles, and hypersonic glide vehicles.17The table on p. 24 depicts the evolution of Chinese ballistic and cruise missiles.

For Chinese observers, the Gulf War reinforced the PLA’s conviction that command and control must be highly centralized. According to Chinese analyses, combining a strong C4ISR network and a “highly centralized defense leadership organ” was the only way to integrate ground, air, and maritime forces in fast-moving, large-scale operations like Desert Storm.18 The disarray and destruction that followed U.S. strikes on Iraqi C4ISR provided a complementary lesson—Chinese adversaries would mercilessly target PLA C4ISR; therefore, it must be redundant and resilient.

In the 1990s, the PLA began building substantial C4ISR networks to support joint military operations and deliver battlespace information dominance. Given China’s limited aerospace industry at the time, developing terrestrial networks became the priority. Beginning in 1994, the PLA embarked on a decade-long renovation of its National Defense Communications Network to high-speed fiber-optic cable.19 Between 1996 and 2003, a war-zone C4ISR network was installed in southeast China, a “theater electronic information system” known by the Chinese abbreviation “Qu Dian.”20 Qu Dian control had expanded nationwide by 2008.21 In the early 2000s, Chinese research institutes developed an “integrated command platform (ICP),” an enterprise architecture to ingest and process large amounts of information, aid in command decision-making, and enable an interoperable joint force.22 By the late 2000s, China had also fielded its own version of the U.S. Link-16 datalink, the “Joint Information Distribution System.”23

The PLA’s foray into space began in 2000, with the launch of its first military communications satellite, its first imaging satellite, and the first Beidou navigation satellite. Since then, China’s military space capabilities have only expanded, especially as the PLA has begun leveraging nominally civil satellites for military use (though even these are nearly all the property of state-owned enterprises). Chinese satellite launches since 2015 have included high-throughput satellites supporting on-the-move communications and dozens of low-earth orbit communication and intelligence-collection satellites.24 The Beidou-3 navigation constellation achieved global coverage in 2020.

China was still building diesel-electric Type 033 attack submarines (left)—known to NATO as the Romeo class—as late as 1984. Despite significant improvements in sound emissions, the Romeos (which first entered service in the late 1950s) were noisy and easy to detect. In 1998, China’s first locally designed class of submarines—the Type 039, NATO reporting name: Song—began to enter service. By most accounts, the Songs are as quiet and capable as any Western diesel-electric sub. Alamy/Reuters (Guang Niu)

By the mid-2000s, special mission aircraft with substantial C4ISR and electronic warfare capabilities emerged as significant force multipliers for PLAAF and PLAN operations. In the past several years, Chinese unmanned aerial systems have integrated with PLA forces to significantly enhance C4ISR capabilities.25 This is to say nothing of the dizzying array of Chinese land- and ship-based radars and electronic warfare systems that together cover a huge swath of the electromagnetic spectrum.26

Forecasting the Next PLA

China took many lessons, large and small, from the Gulf War, ranging from insights about combat logistics to the use of night-vision technology. Beyond any individual lesson, though, the Gulf War showed the PLA how modern wars were fought and provided a road map to become a world-class military. China’s 2015 Military Strategy explicitly states how the PLA expects to fight and win modern wars: “Integrated combat forces will be employed to prevail in system-of-systems operations featuring information dominance, precision strikes on critical nodes and joint operations [emphasis added].”27

The PLA reorganized in 2016 to align with priorities identified in the 2015 strategy and the many lessons of the Gulf War. The military region construct that had provided the defensive foundations of the people’s war was finally abandoned. A PLA joint staff was created, and China was organized into five theaters staffed by all services to facilitate offensive joint operations. A new military service–level element, the Strategic Support Force, was created to integrate information capabilities, including cyber, electronic warfare, and space capabilities. The Second Artillery Corps, responsible for nuclear and conventional ballistic missiles and a large proportion of long-range strike capabilities, was elevated to a military service and renamed the PLA Rocket Force. A PLA Army staff also was created, finally distinguishing ground forces from the other services, creating equivalency and jointness with the PLAN and PLAAF.

Where will the PLA be in 30 years? Will China ever be able to execute an overseas operation approaching the size and scale of Operation Desert Storm? Much has been made of a handful of Chinese ships on counterpiracy patrols and a small garrison of PLA troops in East Africa as hallmarks of Beijing’s military aspirations. Better indicators of PLA priorities may be found in the country’s investments in nuclear attack submarines, aircraft carriers, cruisers, big-deck amphibious ships, heavy-lift aircraft, and global C4ISR coverage. These long-range expeditionary capabilities may have some utility in a local conflict like a Taiwan or South China Sea scenario, extending China’s defensive lines farther into the western Pacific and Indian Ocean. However, defending China’s overseas interests is an increasingly important mission for the PLA.

Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative significantly extends Chinese economic interests into South and Southwest Asia, Africa, and South America. Looking back at the lessons China learned from the Gulf War and closely monitoring Chinese investments over the next 30 years will provide the best indication of how and where the PLA may try to realize its “world-class” ambition.

No comments:

Post a Comment