As the EU struggles with shortages and delays in vaccine supplies, Central and Eastern European countries have looked to Beijing for support. Serbia – EU candidate country and close friend of China – has already received 1,500,000 doses of the Chinese vaccine Sinopharm. Hungary received its first 550,000 doses in February. The Hungarian government plans to inoculate 250,000 people a month with the Chinese product between now and April. Meanwhile, Montenegro is waiting to receive a donation of 30,000 doses.

China’s vaccine diplomacy appears to be bearing fruit in these countries, and that threatens to deepen the rift between them and Brussels. Eurosceptic leaders have consistently played up Chinese support at the same time as discrediting the EU. "I come to the airport not only to receive the high-quality vaccines, but to demonstrate the friendship between China and Serbia," said Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic as he welcomed the first batch of the Sinopharm vaccine at Belgrade airport in January. He did not grant the Pfizer-Biontech and Sputnik V vaccines a similar high-profile reception. In Hungary, the first EU country to approve a purchase of Sinopharm, Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto called the EU’s vaccine procurement “scandalously slow”.

Beijing works hard to shape the narrative of its role in the pandemic

Such statements are usually swiftly picked up by Chinese party-state media. They play into the hands of China’s propaganda efforts to present a favorable story of its successful pandemic response. Beijing has used mask and vaccine diplomacy to counter an image widespread in Europe – that of China being responsible for the pandemic due to its lack of transparency and sluggish measures in the first months of the outbreak. As part of this public diplomacy push, Chinese vaccine makers are reportedly exporting more doses abroad than have been distributed in China.

High-profile Chinese public diplomacy campaigns in Europe have been a recurring theme throughout the pandemic. In the early phases, medical supplies including face masks that had been ordered and paid for by European recipients were incorrectly described as “generous donations” in party-state news coverage. Images of shipments arriving at European airports carrying the PRC’s flag and that of recipient country flooded social media platforms along with messages of gratitude for China’s support, all helped by a number of fake accounts.

Discrediting Western-made vaccines domestically is the order of the day

With the beginning of mass inoculation campaigns, Beijing has focused its propaganda efforts on discrediting Western-made vaccines. Chinese party-state broadcasters spread unverified stories about health risks posed by the Pfizer-Biontech vaccine, touting Chinese alternatives as better. The EU would be wise to counter these narratives with social media information campaigns presenting data on vaccines approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

While the availability of additional Chinese options should certainly be welcomed, it seems Chinese manufacturers are not particularly keen on having their products licensed for the European market. So far, no Chinese vaccine maker has sought authorization from the EMA for the use and distribution of their vaccine. To do that, they would need to hand over their trial data to allow for an assessment of their products’ safety and efficacy. Less promotion – legitimate or otherwise – and greater transparency about its vaccines would go a long way towards improving China’s reputation in the EU.

Portugal plans to use its EU Council Presidency to diversify the EU’s ties with Asia

Portugal is now one month into its six-month rotating Presidency of the EU Council, after picking up the baton from Germany in January. At first sight, China plays a minor role in Lisbon’s official Presidency program. It is mentioned only twice in the following context:

Finalizing Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) and implementing the 2020 EU-China Geographical Indications Agreement as a trade partner.

Forwarding the EU’s biodiversity agenda as the host of the 2021 UN Conference on Biodiversity.

However, Beijing will be the elephant in the room in many of Lisbon’s foreign policy objectives, among them:

Reviving transatlantic cooperation with the new US administration.

Diversifying partnerships in the Indo-Pacific.

Establishing a high-level EU-India dialogue.

Strengthening the EU’s partnership with Africa.

MERICS take: A signatory to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, Portugal has worried EU partners in the past over its openness to Chinese capital. State-owned China Three Gorges is the largest shareholder in Portugal’s leading energy company EDP, and Chinese investors have been among the top beneficiaries of the country’s controversial golden visa program - providing foreign investors with resident permits. The EU and the United States are also closely watching China’s participation in the tender for the geostrategically important port of Sines.

Against this background as well as Portugal’s reluctance to clash with China over human rights issues, the Chinese Ambassador to the EU, Zhang Ming has expressed high hopes that the Portugal presidency will provide a “very big boost” to the process of finalizing the CAI. But while the Presidency is committed to making CAI a success despite Washington’s dissatisfaction, Beijing may find Lisbon to be a problematic partner on other fronts.

Portugal’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Augusto Santos Silva has pointed to Beijing as the main target of the EU’s strategic autonomy and the position is evident in the Presidency’s geopolitical goals. The key priority is increasing the EU’s standing in the Indo-Pacific, which translates to limiting economic dependency on China, and countering Beijing’s influence in the region. This stems from plans to promote open trade and the rules-based international order, in line with the Indo-Pacific strategies of France, Germany and the Netherlands.

What to watch: The main event of the Portuguese Presidency is going to be the EU-India Summit gathering of heads of state and government scheduled for May. Lisbon hopes to make the summit a recurring high-level dialogue. Its outcome will have an impact on the EU’s ability to build influence in the region and diversify its relations away from China.

Transatlantic allies see Beijing’s challenges through different lenses

Transatlantic discussions on China between European leaders and US President Joe Biden’s administration have been launched among a spree of exchanges. NATO Defense Ministers and G7 leaders discussed security and economic challenges posed by Beijing. Biden also exchanged views on China with German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron during the Munich Security Conference. US State Secretary Antony Blinken joined the Foreign Affairs Council meeting of EU Foreign Ministers.

These meetings served as the first attempts to define a concrete transatlantic agenda for addressing the challenges posed by China. They also provided Biden with an opportunity to respond to the proposal made last year by the European Commission’s for a strategic agenda for cooperation with the United States, including issues pertaining to China policy.

MERICS take: Allies have different priorities. There seems to be a consensus on cooperating on China’s economic practices and getting Beijing to play by international rules. But President Biden’s message of preparing together for “long-term strategic competition with China”, framed as a clash between democratic and authoritarian political models, finds less support among European leaders. The EU seems to prefer a selective, technocratic approach to cooperation that will not hinder its ability to develop economic ties with China – at least for now.

There is also the underlying issue of trust. While Biden’s pro-transatlantic agenda is welcomed across Europe, as the result of the four years of the Trump presidency, the EU is now committed to building up its own capabilities as part of quest to enhance its strategic autonomy. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel stated quite plainly, “our interests will not always converge.”

What to watch: The Transatlantic cooperation on China will likely be launched through the creation of practical, focused mechanisms like the EU-US Trade and Tech Council. The EU’s review of implementation of its EU-China Strategic Outlook, scheduled for March, will also be a chance for the EU to show its current political sentiment on China. It will signal whether the bloc wants to take up some of the more confrontational aspects of the United States’ approach to China or if the EU will continue with its current policy of compartmentalizing geopolitical and economic considerations.

17+1 summit: divisions emerge between Central and Eastern European countries on China policy

The recent 17+1 summit was the first ever to be presided over by President Xi Jinping. However, this could not disguise growing dissatisfaction among some participating countries with their big Asian partner. At the meeting held online on February 9, six out of 12 EU states participating in the format – the Baltic states, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovenia – were represented by ministers only and not the usual heads of state or government.

The summit participants failed to agree on a usual joint statement or a date for the next meeting. China’s promise to import USD 170 billion worth of goods from CEE over the ext five years – including doubling the imports of agri-food products – may not be enough to win over the sceptics given that past economic promises made by Beijing to the region have rarely materialized.

The future of the format, which is contested in Brussels and in Western European countries, is unclear. It is possible that the participation of CEE countries will become voluntary in future or that the summit will be moved to biannual format.

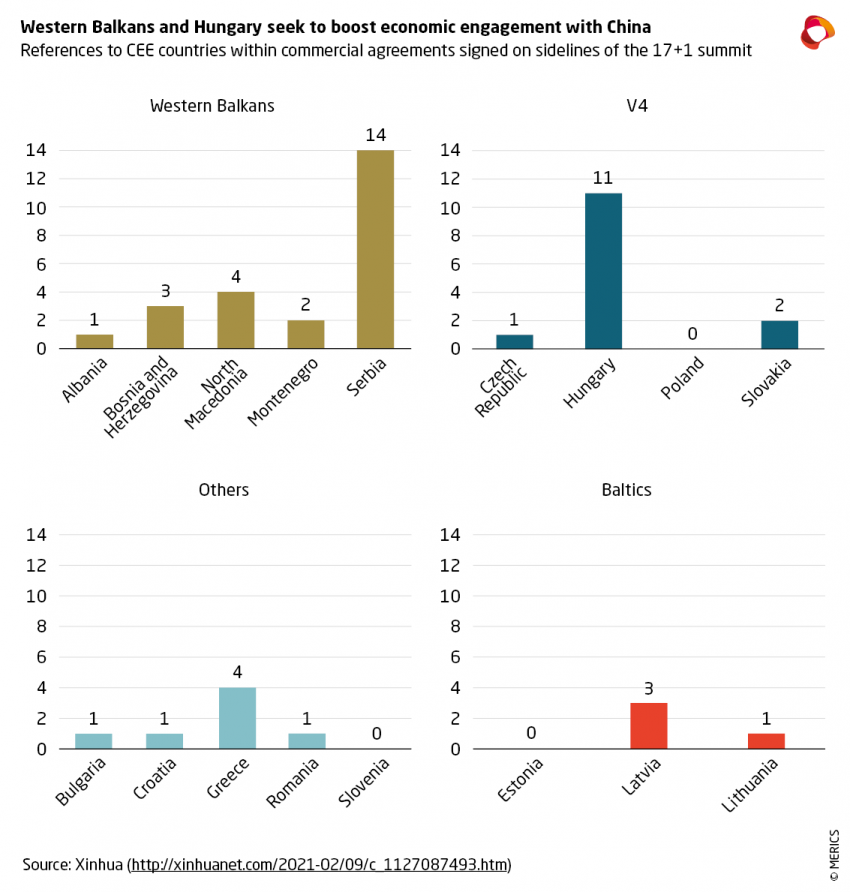

What to watch: The growing skepticism over China is particularly visible in the Baltic countries. Following the summit, Lithuania will reassess the security risks arising from Chinese companies’ involvement in infrastructure projects, and Estonia cautioned against Beijing’s efforts to divide Europe and the United States. It appears that Chinese efforts will now be focused on Western Balkan countries. These received almost half of the mentions in the action plan released after the summit, while the Baltic states received not a single reference.

MERICS take: The outcome of the summit reflects several Central and Eastern European countries’ disillusionment. Disappointed with the platform’s economic results, they are increasingly willing to take a more assertive stance towards Beijing. This also allows them to score points with Washington – the main security provider in a region that is mindful of the challenges posed by Russia. However, the reaction is not uniform. A North-South divide seems to be emerging, which may lead to some readjustment in the format.

Meanwhile, Brussels and Western European capitals remain suspicious and consider the format a tool for China to exercise influence in Central and Eastern Europe with the aim of undermining European unity on China. An accurate and nuanced assessment of the condition of the platform and CEE countries’ relations with China will be crucial for Brussels in its efforts to develop and maintain a more united China policy and to respond to Beijing’s influence push in the Balkans.

No comments:

Post a Comment