By Joel Wuthnow & Phillip C. Saunders

A linchpin of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s transformation into a “world-class military” is whether it can recruit, cultivate, and retain talent, especially among the officer corps tasked with planning and conducting future wars. Uneven progress over the past few decades has meant that deeper reforms to the officer system are necessary under the leadership of Central Military Commission (CMC) Chairman Xi Jinping (习近平). New regulations announced in January 2021 suggest a commitment to clarifying hierarchical relationships between officers, improving the officer management system, incentivizing high performers, and recruiting and retaining officers with the right skills. Nonetheless, several challenges and complications remain.

Background

The new regulations are the latest step in a long but uneven path towards professionalization. The process began in the 1950s under then-Defense Minister Peng Dehuai (彭德怀) but was suspended just prior to the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), during which the PLA focused more on political indoctrination than developing professional skills, and even abandoned formal ranks for a time. Officer ranks were not restored until the issuance of the Active Duty Officer Law in 1988 (Xinhua, May 12, 2014), itself part of a larger effort under then-paramount leader Deng Xiaoping (邓小平) to professionalize the personnel system through formal rules and policies. Under the leadership of former CMC chairmen Jiang Zemin (江泽民)(1989-2004) and Hu Jintao (胡锦涛) (2004-2012), the PLA made further changes to recruitment and retention policies, military training and education, pay and welfare, and related areas, to promote the army’s evolving focus on fighting and winning “high-tech local wars.”(高技术局部战争, gaojishu jubu zhanzheng)[1]

Those earlier steps were apparently unsatisfactory. PLA commentary over the last decade has frequently criticized officers as mentally and professionally ill-equipped to handle the demands of modern war.[2] Moreover, corruption flourished in the PLA during the Hu period, with widespread bribery for promotions and assignments to senior positions.[3] As early as October 2013, the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Committee referenced the need to “build a system of officer professionalization” (Xinhua, November 12, 2013). The CMC endorsed this focus on revising the officer system in the general PLA-wide reform plan issued in November 2015 (Xinhua, November 26, 2015). Those changes are now part of the final phase of regulation and policy reforms, following earlier changes to the command structure, force composition (including culling thousands of non-combat-focused officers from the ranks), and training and education systems.[4] Officer system reforms also followed changes to other parts of the PLA workforce, including conscripts, NCOs, and civilians.[5]

An early clue on how the officer system might evolve came in late 2016, when former CMC Political Work Department director Zhang Yang (张阳) stated that “building a new officer management system based on military rank” is an “inevitable choice…for modern military construction” (Xinhua, December 20, 2016). Since the 2015 reforms prioritized larger structural changes to the PLA, in-depth consideration of officer system reforms did not begin until 2019 (PLA Daily, January 9). On January 1, 2021, the CMC promulgated a series of “one basic and eight supporting” regulations (法规 fagui). The former “lays the foundation for the officer system,” while the latter detail changes to specific areas such as promotion, appointments, education, assessments, pay, and retirement (PLA Daily, January 9). Beijing has not released the full text of the new regulations but remarks by a PLA spokesman and commentary have yielded some potential insights.

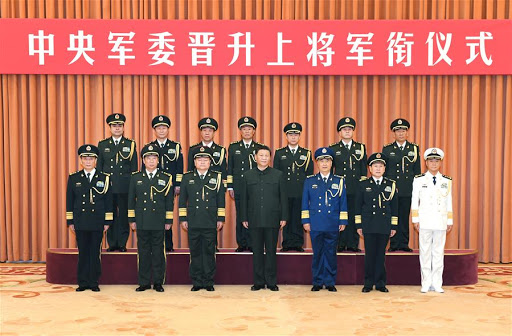

Image: The promotion of seven military officers to the rank of general in December 2019. (Image source: Xinhua)

Moving Towards a “Rank-Centric” System

The major change involves moving to an officer hierarchy centered primarily on rank rather than grade. Understanding this change requires a short primer on the hierarchy of PLA officers. In the Chinese system, PLA officers possess both one of 10 ranks (军衔 junxian) and one of 15 grades based on position (职务等级 zhiwu dengji) (see table for details).[6] An officer’s grade was more important than rank as a determinant of his or her authority, as well as status, pay, and benefits. The grade-centric system was based on PLA ground force structure, with every PLA organization having a grade corresponding to its position in the organizational hierarchy, and officers in turn having a grade based on their positions in their organization.

Because of the lack of a commensurate number of ranks and grades and misaligned promotion cycles—officers typically receive a rank promotion every four years and a grade promotion every three years—officers at a given grade might have different ranks and vice versa. This led to confusing situations in which lower-ranked officers with high grades sometimes effectively outranked higher-ranked officers with low grades.

Table: PLA’s 15-grade and 10-rank Structure, 1988-2020

Structural reforms pursued under Xi created additional problems for a primarily grade-based officer system. Many organizations changed who they reported to and were reduced in grade to reflect their new responsibilities and position. At the same time, many senior PLA leaders changed assignments but kept their existing grades and ranks (even if their new positions were lower) so that they could serve until their mandatory retirement age based on grade. Compounding the problem, the reforms accelerated and formalized a shift from a four-tiered (corps-division-regiment-battalion) structure to a three-tiered (corps-brigade-battalion) structure that did not mesh with the grade system; for instance, there were now Division Leader grade officers without divisions to command.[7] The PLA could have revised the grade system to match the new structure (potentially unifying grades and ranks for each position in the new hierarchy), but this solution was not implemented because some divisions and regiments still exist.

In this context, the 2021 regulations aimed to create a clearer officer hierarchy centered around military ranks, as foreshadowed by Zhang Yang’s 2016 remarks. Now the “basic order in managing authority” will be governed by rank, which will also play a key role in career development, while grade will be confined to an “auxiliary” status (MND, February 1). Chinese commentary argues that this new emphasis will establish clearer relationships between officers—a function necessary during wartime when units may be reassigned and relations between commanders and subordinates realigned (Sina, January 13). This change will also facilitate assignments to new organizations or to joint positions where officers from different services must work together. Non-authoritative sources also suggest better synchronization in promotion cycles. Operating on a parallel promotion schedule would reduce disparities in grade among officers at the same rank (Sina, January 13).[8]

Additional Reforms

Aside from reforming the rank and grade system, the latest regulations aim to improve professionalization in two other ways. First is promoting the standardization and specialization of officer positions. The 2000 update to the Active Duty Officer Law divided officers into five types: military affairs, political, logistics, equipment, and technical (Xinhua, May 12, 2014). However, a CMC Political Work Department commentary describes this system as “expansive,” with loose boundaries between career fields, and complicated by “inconsistent training, random changes in careers, and disorderly competition” (Pengpai, December 5, 2016).

The 2021 reforms created a new classification system to correct these problems. At the broadest level, the system distinguishes between command and administrative officer positions (指挥管理岗位 zhihui guanli gangwei) and technical specialist positions (专业技术岗位 zhuanye jishu gangwei). The new system appears to retain a political (政治 zhengzhi) specialization and to distinguish between operational command (指挥 zhihui) and staff (参谋 canmou) positions, with the latter focused on force development. Some command and administrative posts are reserved for officers from specific services and branches, while others are not (i.e., “joint positions” in U.S. terminology). Technical specialists have different recruitment pathways, five distinct areas of specialization, and a distinct four-tiered grade structure (MND, January 28).[9]

The new categorization brings the officer system into better alignment with the PLA’s new organizational structure. An aim of the personnel system reform appears to be cultivating officers with specialization in either the operational or administrative chain of command and promoting more consistent training, education, and assessments between officers in similar positions (though it hasn’t been clarified whether an officer can move between tracks).[10] The PLA also claimed that a more systematic classification of technical officers would “facilitate the attraction, cultivation, and utilization of talent on a broader base” (MND, January 28).[11]

The second reform strengthens the recruitment and retention of high performers and personnel with sought-after skills and experiences. The PLA has identified a need for further increases in pay and welfare benefits to produce “motivation and vitality” among officers and compete with the private sector for talent (PLA Daily, January 9).[12] Consequently, the new system introduces a 19-tier officer salary and benefits scale loosely linked to rank (MND, January 28). This allows officers to be rewarded for good performance without having to wait until the next promotion cycle. Officers with valuable skills who have reached their promotion ceilings can also still receive pay raises to keep them in the military.

In a further effort to attract a high-quality officer corps, the PLA announced that an officer’s initial rank would be influenced by his or her education and experience level. For example, a master’s degree holder would enter as a first lieutenant, while a newly minted Ph.D. would enter as a captain. Those with “high-demand” skills, presumably in areas such as cyber and engineering, would be assigned a rank that takes their education and work experience into account (MND, January 28). These changes complement the shift to a “rank-centric” system in which salary and benefits are influenced primarily by rank.

Conclusion: Implications and Challenges

Reforms to the officer system may broadly help to clarify hierarchical relations between officers and attract and manage an officer corps better suited to the demands of future warfare. Some of the reforms may also set the stage for more ambitious changes. For example, standardization of officer categories in a way that reflects the PLA’s new organizational structure and more uniform assessment and promotion standards would be a prerequisite for transitioning from the use of local promotion boards, in which patronage networks play a key role, to central promotion boards focused more on merit (albeit with potential for political interference from central leaders);[13] and from an assignment system in which officers spend most their careers in a single location to a rotational system in which they gain experience across a broader range of commands (although some challenges, such as housing issues, could still stand in the way of a quick shift to this system).[14]

The effectiveness of these changes will depend on the PLA’s ability to overcome several challenges. First, despite efforts to streamline the officer system, the PLA elected to keep both ranks and grades. Earlier PLA sources described a transition to a system of “one grade to one rank” (PLA Daily, February 16, 2016), yet the more complex system of one grade to multiple ranks (and vice versa) remains in place. If the PLA intends to focus on rank, it will have to implement supporting changes such as formally aligning rank and grade promotion cycles; eliminating the few remaining divisions and regiments (which would be a prerequisite for a reduction in the number of possible grades); speeding up promotions in rank for “fast burners” who have been elevated in grade but not in rank; allowing officers to skip a grade and pegging retirement ages and benefits to rank rather than grade.

A related question for the PLA is defining what purpose grade will serve in a rank-centric system. PLA sources have described grade playing an “auxiliary” role in determining promotions and assignments, without much further elaboration (MND, January 28). One possibility is that an officer’s grade will become a “tie-breaker” in determining seniority between officers at the same rank, much as job billet or service time sometimes influences authority between U.S. officers at the same rank.

Second is how effectively the PLA can manage officer career progression. One problem the PLA continues to face is maintaining an appropriate balance of officers at different career stages: excessively fast promotion of junior officers has thinned expertise at the company level while creating a surplus of senior officers, even after the recent 300,000-person downsizing and earlier reforms that permitted officers to leave active service before reaching the mandatory retirement age. This situation has led the PLA to both slow down promotions at the junior level while reducing mandatory retirement ages for officers above the rank of colonel (PLA Daily, January 9). Yet instituting those changes could come at the expense of enhancing “motivation and vitality” in the officer corps if not well-managed through new incentives and a more effective officer management system: junior officers stuck at lower levels could be tempted to leave while senior officers with useful skills and experience may resent having to retire early.

Third is overcoming external competition for officer candidates with desired skills. Despite advantages such as relative job stability, social status, and various fringe benefits, the PLA still lags far behind the private sector for total compensation in some technical skill sets. For instance, while a new PLA cyber expert may earn total annual compensation of roughly 84,000 RMB (as of 2018),[15] with a bonus for technical skills, the reported monthly starting salary for a cyber expert at Alibaba is more than 50,000 RMB.[16] These disparities have resulted in concerns about how to both attract and retain talent. In short, the PLA has taken a step forward in professionalizing the officer system but will continue to face hard choices to build an officer corps which can, in Xi Jinping’s words, “fight and win battles.”

Thanks to Ken Allen, Dennis Blasko, and Rick Gunnell for comments on an earlier draft of this article. This article represents only the views of the authors and not those of National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Dr. Joel Wuthnow is a Senior Research Fellow in the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at the U.S. National Defense University. He also serves as an adjunct professor in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. Among other volumes, he is the lead editor of The PLA Beyond Borders: Chinese Military Operations in Regional and Global Context (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2021).

Dr. Phillip. C. Saunders is the Director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at the U.S. National Defense University. He is the author or editor of many books on the PLA, including Chairman Xi Remakes the PLA: Assessing Chinese Military Reform (Washington, DC: NDU Press, 2019).

No comments:

Post a Comment