Loren Thompson

President Biden made good on one of his campaign promises this week by extending the last Cold War arms control agreement still in force for another five years, to 2026.

Called New START, for “strategic arms reduction treaty,” the agreement limits Russia and America to 1,550 nuclear warheads carried on no more than 700 long-range delivery systems—land-based ballistic missiles, sea-based ballistic missiles and heavy bombers.

The main goal of the treaty is to foster a stable and verifiable nuclear balance in which there is minimal likelihood of misunderstandings between Washington and Moscow.

Misunderstandings can lead to mistakes in a crisis—fatal mistakes if either side resorts to the use of their weapons.

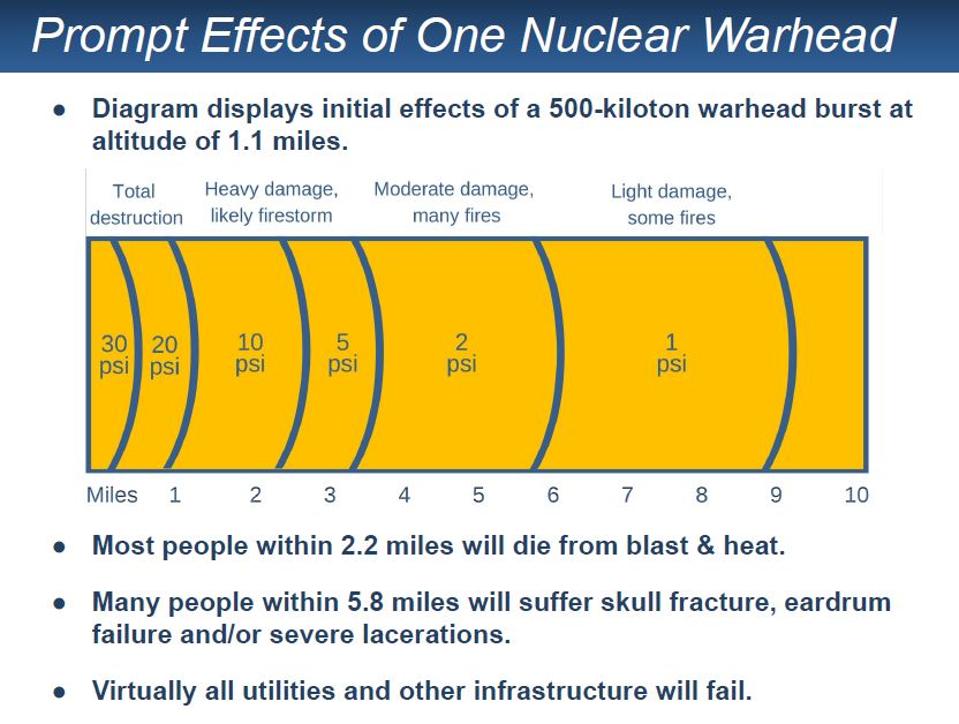

As the following chart indicates, a single warhead of typical yield for the Russian arsenal, detonated above a major U.S. city, would likely kill more Americans in an hour than Covid-19 has in a year. The Russians have 700 such warheads aimed at the U.S., plus hundreds of additional, lower-yield warheads.

Pressure in pounds per square inch (psi) above ambient generated by a nuclear shock wave. Effects of ... [+] LOREN THOMPSON

It is impossible to defend either nation against a large-scale attack using weapons of such fearsome power. If only 5% of incoming weapons penetrated defenses, that would probably be sufficient to collapse the economy and social structure of either nation.

So New START doesn’t try to blunt the impact of a nuclear exchange. What it does is create a nuclear balance in which there is no rational incentive to launch first.

Each side knows it cannot disarm the other in a surprise attack, and that any act of nuclear aggression would provoke overwhelming retaliation. In other words, launching a nuclear attack would likely prove suicidal for either side.

Virtually everything that Washington and Moscow have done with their nuclear forces since the first strategic arms treaty went into effect in 1972 has been aimed a reinforcing this perception. Attack me and you die.

That may not be a comforting strategy, but it apparently is the best we can do in the nuclear age—at least when dealing with rivals who possess over a thousand long-range warheads.

However, there is a looming problem with the U.S. retaliatory force that Deputy Secretary of Defense-designate Kathleen Hicks highlighted in her confirmation hearing before Congress this week.

Because Washington has delayed and delayed modernizing its Cold War nuclear arsenal, many of the weapons will soon cease to be reliable. In fact, Hicks intimated that decay may have already begun, observing “I am worried about the state of readiness of the Triad.”

The Triad is the force of land-based missiles, sea-based missiles, and long-range bombers that collectively comprises America’s retaliatory force.

Due to a combination of wishful thinking and bad management in previous administrations, all three legs of the Triad are facing forced retirement beginning at the end of this decade:

The 400 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles deployed in hardened underground silos across the upper Midwest are 50 years old, and despite repeated life-extension initiatives will not be reliable beyond 2030.

The 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines hosting 70% of U.S. strategic warheads, which have also seen their original design lives extended, must begin retiring in 2030.

The 66 nuclear capable bombers operated by the Air Force’s Global Strike Command will be unable to reach most strategic targets after 2030 unless their aged cruise missiles are replaced.

The Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff recently observed that it is “a miracle” the latter weapons can still fly at all. Originally intended to operate for ten years, they are approaching their fifth decade of service.

So to put it succinctly, the entire U.S. nuclear deterrent is aging out, rapidly approaching retirement.

President Obama and President Trump understood this, and therefore put in place programs to modernize all three legs of the Triad, plus the command-and-control network and missile-warning satellites.

It now falls to President Biden to keep this effort moving forward, because Washington is out of time for deliberations if it wants to preserve a credible retaliatory capability—the bedrock requirement of security in the nuclear age.

Some Democrats have advanced fanciful notions of how money might be saved in modernizing the nuclear arsenal, perhaps by foregoing the purchase of Minuteman III replacements or better cruise missiles for the bombers. However, as the Obama-Biden 2010 nuclear posture review stated, “Each leg of the Triad has advantages that warrant retaining all three legs at this stage of reductions.”

The Trump administration’s nuclear posture review came to a similar conclusion: “Eliminating any leg of the Triad would greatly ease adversary attack planning and allow an adversary to concentrate resources and attention on defeating the remaining two legs.”

Said differently, eliminating any part of the current modernization plan makes nuclear war more likely, by increasing the likelihood that Russia (or China) one day decides it can disarm America in a surprise attack.

That possibility might seem far-fetched, but there is a long history of false warnings and regional crises that nearly led to fatal misjudgments in the past.

So let’s not fool ourselves about what arms control can accomplish. The stable nuclear balance enshrined in New START is grounded in Moscow’s awareness that any act of nuclear aggression could prove suicidal.

The Biden administration needs to assure that Russian leaders, no matter how deluded or besieged, won’t come to a different conclusion in the future.

No comments:

Post a Comment