By Elisabeth Eaves

America is building a new weapon of mass destruction, a nuclear missile the length of a bowling lane. It will be able to travel some 6,000 miles, carrying a warhead more than 20 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It will be able to kill hundreds of thousands of people in a single shot.

The US Air Force plans to order more than 600 of them.

On September 8, the Air Force gave the defense company Northrop Grumman an initial contract of $13.3 billion to begin engineering and manufacturing the missile, but that will be just a fraction of the total bill. Based on a Pentagon report cited by the Arms Control Association Association and Bloomberg News, the government will spend roughly $100 billion to build the weapon, which will be ready to use around 2029.

To put that price tag in perspective, $100 billion could pay 1.24 million elementary school teacher salaries for a year, provide 2.84 million four-year university scholarships, or cover 3.3 million hospital stays for covid-19 patients. It’s enough to build a massive mechanical wall to protect New York City from sea level rise. It’s enough to get to Mars.

One day soon, the Air Force will christen this new war machine with its “popular” name, likely some word that projects goodness and strength, in keeping with past nuclear missiles like the Atlas, Titan, and Peacekeeper. For now, though, the missile goes by the inglorious acronym GBSD, for “ground-based strategic deterrent.” The GBSD is designed to replace the existing fleet of Minuteman III missiles; both are intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs. Like its predecessors, the GBSD fleet will be lodged in underground silos, widely scattered in three groups known as “wings” across five states. The official purpose of American ICBMs goes beyond responding to nuclear assault. They are also intended to deter such attacks, and serve as targets in case there is one.

Defense industry concepts for the proposed GBSD missile (left to right: Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman). In September 2020, after Boeing had dropped its bid, the US Air Force awarded Northrop Grumman the initial $13.3 billion contract.

Under the theory of deterrence, America’s nuclear arsenal—currently made up of 3,800 warheads—sends a message to other nuclear-armed countries. It relays to the enemy that US retaliation would be so awful, it had better not attack in the first place. Many consider American deterrence a success, pointing to the fact that no country has ever attacked the United States with nuclear weapons. This argument relies on the same faulty logic Ernie used when he told Bert he had a banana in his ear to keep the alligators away: The absence of alligators doesn’t prove the banana worked. Likewise, the absence of a nuclear attack on the United States doesn’t prove that 3,800 warheads are essential to deterrence. And for practical purposes, after the first few, they quickly grow redundant. “Once you've dropped a couple of nuclear bombs on a city, if you drop a couple more, all you do is make the rubble shake,” said Air Force Maj. Gen. (Ret.) Robert Latiff, a Bulletin Science and Security Board member who, early in his career, commanded a unit of short-range nuclear weapons in West Germany.

Deterrence is the main argument for having a nuclear arsenal at all. But America’s land-based missiles have another strategic purpose all their own. Housed in permanent silos spread across America’s high plains, they are intended to draw fire to the region in the event of a nuclear war, forcing Russia to use up a lot of atomic ammunition on a sparsely populated area. If that happened, and all three wings were destroyed, the attack would still kill more than 10 million people and turn the area into a charred wasteland, unfarmable and uninhabitable for centuries to come.

The GBSD’s detractors include long-time peace activists, as you’d expect. But many of the missile’s critics are former military leaders, and their criticism has to do with those immovable silos. Relative to nuclear missiles on submarines, which can slink around undetected, and nuclear bombs on airplanes—the two other legs of the nuclear triad, in defense jargon—America’s land-based nuclear missiles are easy marks.

Because they are so exposed, they pose another risk: To avoid being destroyed and rendered useless—their silos provide no real protection against a direct Russian nuclear strike—they would be “launched on warning,” that is, as soon as the Pentagon got wind of an incoming nuclear attack. But the computer systems that warn of such incoming fire may be vulnerable to hacking and false alarms. During the Cold War, military computer glitches in both the United States and Russia caused numerous close calls, and since then, cyberthreats have become an increasing concern. An investigation ordered by the Obama administration in 2010 found that the Minutemen missiles were vulnerable to a potentially crippling cyberattack. Because an error could have disastrous consequences, James Mattis, the former Marine Corps general who would go on to become the 26th US secretary of defense, testified to the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2015 that getting rid of America’s land-based nuclear missiles “would reduce the false alarm danger.” Whereas a bomber can be turned around even on approach to its target, a nuclear missile launched by mistake can’t be recalled.

William J. Perry, secretary of defense during the Clinton administration (and the chair of the Bulletin’s Board of Sponsors), argued in 2016 that “[w]e simply do not need to rebuild all of the weapons we had during the Cold War” and singled out the GBSD as unnecessary. Replacing America’s land-based nuclear missiles, he wrote, “will crowd out the funding needed to sustain the competitive edge of our conventional forces, and to build the capabilities needed to deal with terrorism and cyber attacks.” Russia has about 4,300 nuclear warheads, the only arsenal on par with America’s, and is also trading up for new weapons. Yet as Perry pointed out, “If Russia decides to build more than it needs, it is their economy that will be destroyed, just as it was during the Cold War.” China—a bigger long-term threat to the United States than Russia, in the eyes of many national security analyses—seems to understand that excessive spending on nuclear weapons would be self-sabotage. Even if, as the Pentagon expects, Beijing doubles the number of nuclear warheads in its arsenal—now estimated at less than 300—it will still have far fewer than either the United States or Russia.

For many and perhaps most Americans, nuclear weapons are out of sight and mind. That $100 billion to replace machines that would, if ever used, kill civilians on a mass scale and possibly end human civilization is just another forgotten subscription on auto-renew. But those who do think about the GBSD mostly don’t want it. In a survey of registered voters conducted in October 2020 by the Federation of American Scientists, 60 percent said they would prefer other alternatives to the new missile, ranging from refurbishing the Minutemen to scrapping nuclear weapons altogether. Those results echo a 2019 voter survey, conducted by the Program for Public Consultation at the University of Maryland, that asked if the government should phase out its fleet of land-based nuclear missiles. Sixty-one percent of respondents—53 percent of Republicans and 69 percent of Democrats—said yes.

Which all leads to one question: Given the expense, doubtful strategic purpose, and lack of popularity, why is Washington spending so much to replace the Minuteman III?

The answers stretch from the Utah desert to Montana wheat fields to the halls of Congress. They span presidential administrations and political parties. They come from airmen and farmers and senators and CEOs.

The reasons for the GBSD are historical, political, and to a significant extent economic. In a country where safety net programs are limited and health insurance is a patchwork, and where unemployment remains at nearly double the pre-pandemic rate, many people in the states where the new missile will be built and based see it as a lifeline. Their elected officials take campaign donations from defense companies, to be sure, but are also trying to deliver jobs in a political environment that has been hostile to government spending on anything but defense. Defense is the safety net where other options are few.

A lot of people, even some of those whose livelihoods depend on them, would like to see the number of nuclear weapons gradually reduced until they’re gone. The United States stands no chance of making them disappear, though, until more people understand why they happen—and how little some nuclear weapons programs have to do with national defense.

Deeply embedded

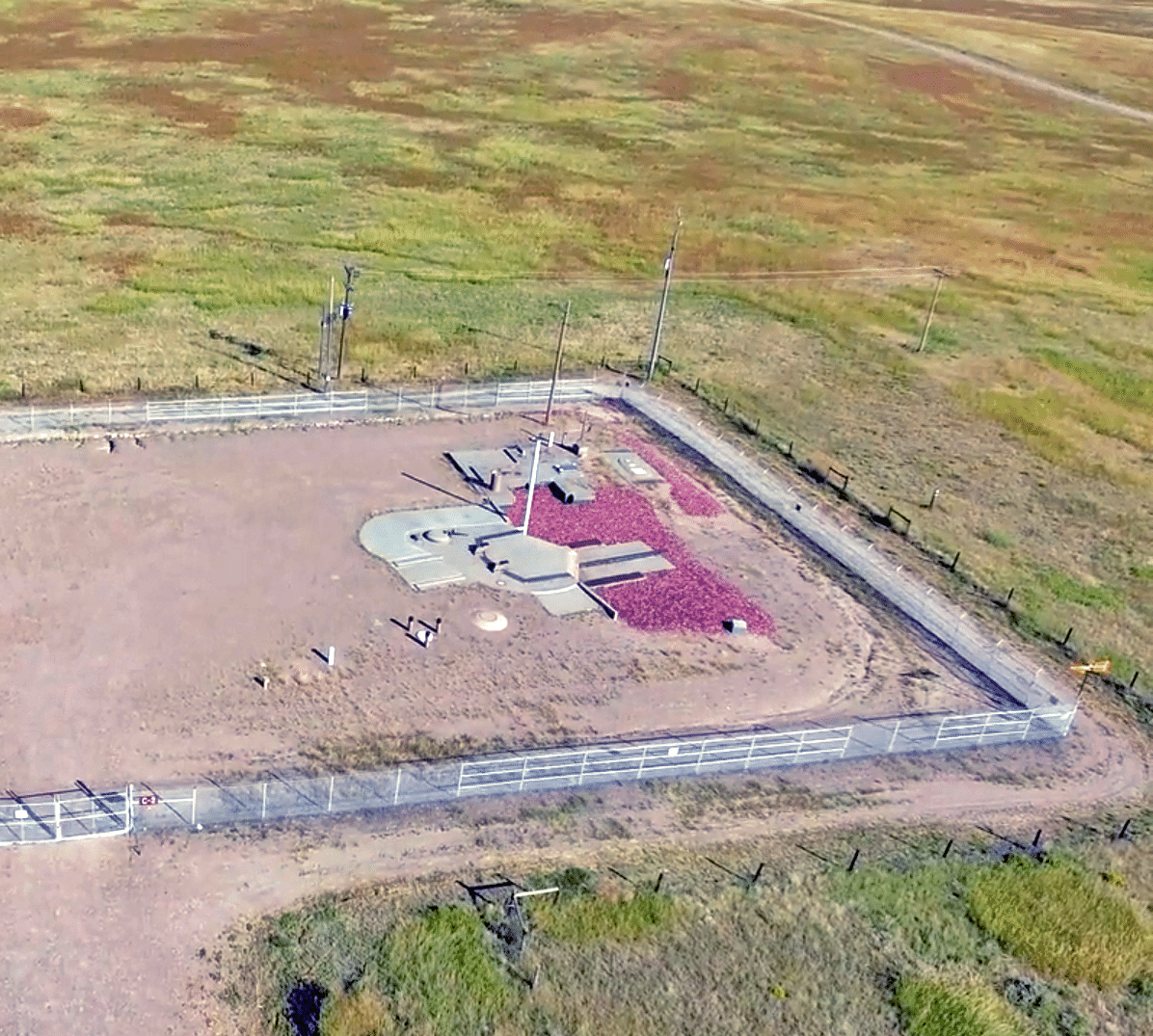

Go looking for a nuclear missile in America’s heartland, and the first thing you’ll see is the porta-potty for maintenance workers. Made of blue or gray plastic, it stands out like a beacon against the natural colors of the surrounding landscape, while the chain link fence and slender antennae are harder to spot at a distance, and the missile itself is underground.

Closer up, you’ll see that the fence, which surrounds an area smaller than a city block, is topped with three strands of barbed wire. Outside the fence, there is a pole mounted with lights, and sometimes an additional pole with cameras. Inside the fence, where the ground may be dirt or gravel, a few poles hold disc-shaped security sensors. A sign on the locked gate says “Use of deadly force authorized,” but there is no sign to indicate the site’s ownership or purpose, no Air Force seal or US flag. When the missile is not being repaired, maintained, or moved, which is most of the time, there is no one present, and rustling grass is often the only sound.

Go looking for a nuclear missile in America's heartland, and the first thing you'll see is the porta-potty for maintenance workers.

Missile silo C-2 in central Montana. (Elisabeth Eaves)

The central structure within the enclosure is a hexagonal lid made of reinforced concrete and steel that sits almost flush with the ground, covering the missile below. The best vantage point for viewing the lid, which sits on tracks, is from the south side of the fence. In the event of a launch, gas charges will shoot the lid southward along the tracks in a matter of seconds, blasting it into the field beyond, to the detriment of any livestock in the way.

There are 450 of these subterranean silos. Four hundred of them hold on-alert nuclear missiles, ready to take off within minutes of a presidential order and hit a target—Moscow or Beijing, Vladivostok or Pyongyang—in 30 minutes or less. The remaining 50 sit empty, following weapon reductions under the New Strategic Arms Control Treaty (New START), signed in 2010 between the United States and Russia.

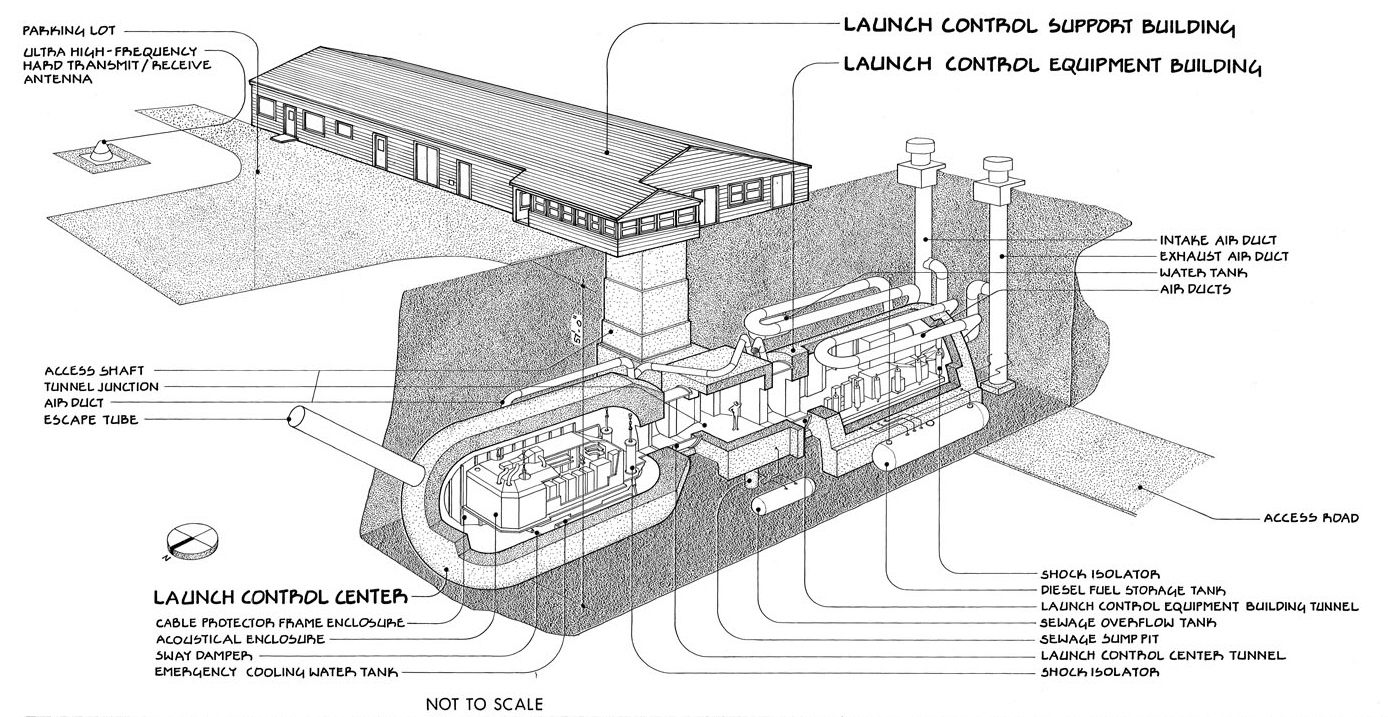

Silos are located several miles from one another. For every 10, there is one staffed launch control facility, to which the silos are connected by steel-encased cables as thick as baguettes. The cables are supposed to be about three feet underground, though some have risen to the surface over the years. “If you’re farming out there, you know where they are,” said Joe Briggs, a commissioner of Cascade County, Montana.

The launch control facilities are easier to spot than the missile silos. Each one includes an above-ground building that looks like an elongated vinyl-sided ranch house, painted an aggressively bland shade of beige and surrounded by a chain link fence. Inside the house are bedrooms, a kitchen, a dining area, and a living room, and outside there may be a basketball hoop. The around-the-clock team on site includes a facility manager, security guards, and a chef.

The officers trained to launch nuclear weapons, known as missileers, toil underground in teams of two. From a secure room inside the house, they ride an elevator down several stories and pass through an eight-ton blast door to reach their post, a submarine-like capsule suspended within an outer shell. Their shifts last 24 hours, although in times of crisis, including during the covid-19 pandemic, shifts can be extended to 36 hours or longer. The capsule is crammed with control consoles and paneled in mid-century metal, like the future imagined in 1963. There is one bunk for lying down, and a missileer may study or rest while his or her counterpart is on watch, but neither of them leaves the capsule during the shift. Inside it stinks of 60 years of sweat and gear. “It's gross. The air is stale, smells of brine and all kinds of old, ancient industrial chemicals that otherwise have been phased out,” said Damon Bosetti, who served as a missileer in Montana from 2006 to 2010. “And it's loud because of all the machinery turning.” The noise comes from a motor-generator that calibrates the power coming into the capsule and the constant whoosh of air conditioning required to keep the electronics cool.

Aerial view of a Minuteman silo in Wyoming. The hexagonal door at center weighs 110 tons, designed to protect against nuclear attacks and debris. There is little else to indicate a multiple megaton nuclear warhead is ready to launch beneath the dirt. (National Park Service)

ICBM launch control facilities feature an above-ground support building with living quarters. Below ground, the Launch Control Center (LCC) contains the communications and launch systems. (Clayton B. Fraser / National Park Service)

Below, left: Alpha-1 in Montana was the first Minuteman LCC, activated in the early 1960s. Each LCC has a two-person crew of missileers, shown here also at Alpha-1. Center right: The two-key launch system is well-known from Hollywood. Right: More than 2,400 miles of pressurized cable connect the facilities in Montana's missile field alone.

US Air Force

Josh Aycock / US Air Force

No comments:

Post a Comment