By Frank N. von Hippel

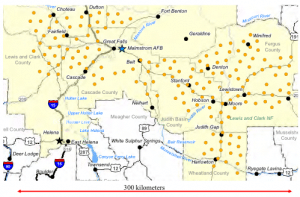

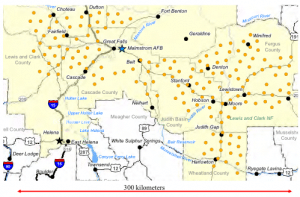

The United States has 400 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) suspended in reinforced concrete underground missile silos, plus an additional 50 empty silos, spaced about 10 kilometers apart near Air Force bases in Montana, North Dakota, and Wyoming (Figure 1). The missiles were originally deployed during the 1970s.

During the Obama administration, the Defense Department launched the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program to replace these ICBMs with an equal number of new missiles, plus spare and test missiles, for a total of 642. In September 2020, the Air Force awarded a $13.3 billion sole-source contract to Northrup Grumman for the weapon system design. The Air Force estimates the project’s capital cost will run to over $100 billion, while the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the total cost, including 30 years of operations, will be $150 billion. Northrup Grumman has spread the work over many states and congressional districts. Its press release states that the work will be carried out in Utah, Alabama, Colorado, Nebraska, California, Arizona, Maryand, and “at our nationwide team locations across the country.” The “team” of subcontractors includes:

“Aerojet Rocketdyne, Bechtel, Clark Construction, Collins Aerospace, General Dynamics, HDT Global, Honeywell, Kratos Defense and Security Solutions, L3Harris, Lockheed Martin, Textron Systems, as well as hundreds of small and medium-sized companies from across the defense, engineering, and construction industries.” Figure 1. Yellow circles show the locations of the 150 Minuteman III silos and 15 launch-control centers associated with Malstrom Air Force Base, Montana.

Figure 1. Yellow circles show the locations of the 150 Minuteman III silos and 15 launch-control centers associated with Malstrom Air Force Base, Montana.

Figure 1. Yellow circles show the locations of the 150 Minuteman III silos and 15 launch-control centers associated with Malstrom Air Force Base, Montana.

Figure 1. Yellow circles show the locations of the 150 Minuteman III silos and 15 launch-control centers associated with Malstrom Air Force Base, Montana.The resulting potent lobbying coalition was able to block a proposed amendent (No. 32) to the House version of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 that called for a new study to examine the possibility of the alternative of extending the life of the Minuteman III again, as has already been done once in the 2000s.

There are strong arguments to be made against the new ICBMs, however, on the basis of their cost, their vulnerability, and the contribution of their launch-on-warning posture to the danger of accidental nuclear war. This piece lays out those arguments in detail and points out that, if Congress is unable to make a decision on eliminating US ICBMs in the next few years, the life of the Minuteman IIIs could be extended to 2060 at a much lower cost than the new ICBM, which is designed to last until 2080.

Budgetary constraints. The huge US federal budget deficit, the need to mitigate the economic distress of many US workers, businesses, and state and local governments in the wake of the cononavirus epidemic, and other budgetary priorities—including climate change mitigation and infrastructure modernization—will inevitably stimulate a search for offsetting savings in forthcoming federal budgets.

The defense budget is an obvious place to look. It accounts for more than half of federal “discretionary” spending—spending that is the subject of the annual budget process. It also is considered by many to be bloated, more than double the combined military budgets of China and Russia—and more than triple, if major US allies are added to the balance. The new administration and a significant fraction of Congress may therefore be open to reconsidering the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program.

Furthermore, the ICBM replacement is only one of five programs underway to “modernize” the US strategic deterrent. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the four others will cost an average of about $250 billion each, including operations over 30 years. These include new ballistic-missile submarines, new strategic bombers and their air-launched cruise missiles, a new nuclear command and control system, and new and life-extended nuclear warheads.

The other modernization programs are less controversial than the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program, however. The ballistic-missile submarines, which carry about half of US deployed strategic warheads, are the most survivable leg of the US nuclear forces; the strategic bombers and air-launched cruise missiles are used for conventional wars as well as nuclear deterrence; the vulnerabilities of the nuclear command and control system to both physical and hacker attacks have been of widespread concern for decades; and nuclear warheads do need to be refurbished periodically.

This has led supporters of the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent program to grasp for reasons why replacing the land-based ICBMs is equally important and urgent.

The core supporters in Congress are the Senate’s “ICBM Coalition”—six Senators from three low-population states: Montana, North Dakota and Wyoming, which host the three missile-base launch-control crews and maintenance workers, plus two Senators from Utah where the missiles are serviced. They believe (as they put it in a 2016 report) in “[t]he Enduring Value of America’s ICBMs” to both the security of the nation and to the economies of their states. Strategic Command has taken responsibility for paving the roads off which its missile silos and launch-control centers are located and directly supports an average of about 1,000 families each on the three ICBM-associated bases with a median family income of about $30,000. For the three states combined, the income from the missile bases is on the order of $100 million per year—about one-thousandth the cost of the ICBM replacement program. It should be possible to conjure up a win-win solution in which a small fraction of the savings from not proceeding with ICBM replacement could be repurposed to programs that would offset the losses to the three states.

Silo-based ICBMs are targetable. The silo-based ICBMs have had their critics for half a century because they are vulnerable to destruction in a preemptive attack. Concerns about a “window of vulnerability” for US silo-based ICBMs date back to the 1970s when it became foreseeable that Soviet ICBMs would become accurate enough to destroy the silos. The proposed solution was mobile ICBMs. Russia and China have, in fact, deployed mobile as well as silo-based missiles. In the United States, however, the proposed mobile system ran into opposition in Utah and Nevada, and the Defense Department abandoned the idea.

US Strategic Command, the part of the US military in charge of US long-range nuclear weapons, argues that the “legs” of the triad—land-based missiles, sea-based missiles, and bombers—have complementary strengths and weaknesses, but the complementary strengths of the ICBMs have almost vanished.

Originally, the unique strength of the ICBMs was their high accuracy and their ability to destroy the Soviet Union’s missile silos and command bunkers. Today, however, the accuracy of the submarine-launched ballistic missiles is comparable to that of the ICBMs.

Another historical strength of the land-based ICBMs was their multiple communication links with US national command posts. But today, communications to US ballistic missile submarines at sea are quite robust. They are able to receive encoded messages via very low frequency signals through long antennas floating near the surface of the ocean and via super high frequency and extremely high frequency relay satellites.

The principal argument for the silo-based ICBMs today is the number of warheads that would be required to destroy them—referred to by critics as the “nuclear-sponge” argument. It goes as follows: If Russia wanted to launch a preemptive attack on US nuclear forces, the existence of the 450 ICBM silos and their associated buried launch-control centers would require Russia to use a large fraction of its own warheads to destroy them, whereas, if the ICBMs in their missile silos did not exist, Russia or China could eliminate the entire US deterrent by locating and destroying only a handful of bomber and submarine bases and about ten US ballistic-missile submarines at sea.

The key question, therefore, is whether the ballistic-missile submarines, though fewer in number, will continue to be survivable in the vastnesses of the deep Atlantic and Pacific oceans for the foreseeable future. As discussed below, the answer appears to be “yes,” but the Biden administration will want to satisfy itself on that point.

Launch on warning. In 1978, the US Defense Department decided, as “an interim measure,” to deal with the vulnerability of the silo-based Minuteman IIIs by posturing the missiles so that, in case of warning of an incoming attack, the missiles could be launched quickly before the attacking warheads arrived. Twenty years later, General Lee Butler, the first commander of Strategic Command (1992–94) stated that the launch on warning posture had become permanent (Strategic Command calls it “launch under attack”) and would be urged on the president. He asserted that Strategic Command had “built a construct that powerfully biased the president’s decision process toward launch before the arrival of the first enemy warhead. And at that point, all the elements, all the nuances of limited response just went out the window. The consequences of deterrence built on massive arsenals made up of a triad of forces now simply ensured that neither nation would survive the ensuing holocaust.”

The flight time of a Russian ICBM would be about 30 minutes. Of this time, the United States would devote about 10 minutes to confirming and assessing the attack with data from US early-warning satellites and radars and about 10 minutes to transmitting and implementing the launch order for the 400 US ICBMs early enough for them to escape before any incoming Russian warheads could arrive.

This would leave the president with about 10 minutes to make a decision that could result in the deaths of millions to billions of human beings. If the attack included a strike on Washington, DC from an offshore Russian ballistic or cruise missile submarine, the amount of time available for decision making would verge on zero.

Before he was elected president in 2008, Barack Obama argued that

[k]eeping nuclear weapons ready to launch on a moment’s notice is a dangerous relic of the Cold War. Such policies increase the risk of catastrophic accidents or miscalculation. I believe that we must address this dangerous situation—something that President Bush promised to do when he campaigned for president back in 2000, but did not do once in office. I will work with Russia to end such outdated Cold War policies in a mutual and verifiable way.

Obama did pursue this goal as president but was rebuffed by the Pentagon. The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review states that the Pentagon “considered the possibility of reducing alert rates for ICBMs and at-sea rates of SSBNs, and concluded that such steps could reduce crisis stability by giving an adversary the incentive to attack before ‘re-alerting’ was complete.”

The linkage of the reduction of the alert level of the ICBMs to a reduction of the at-sea rate and hence the survivability of the ballistic missile submarines was a disingenuous conflation.

The report from the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review simply endorsed the logic of preserving a launch-under-attack option for the ICBMs: “The capability to launch ICBMs promptly means that no adversary can be confident in its ability to destroy them prior to launch. This option contributes to deterrence of a nuclear first strike attack.”

Transition the US strategic triad to a dyad? In 2016, former Secretary of Defense William Perry published an op-ed in the New York Times titled, “Why It’s Safe to Scrap America’s ICBMs.” In 2020, he coauthored a second op-ed, this one for the Washington Post, reiterating the argument:

These dangerous missiles are not needed for deterrence, as we would use survivable weapons based on submarines at sea for any retaliation. Yet ICBMs increase the risk that we will blunder into nuclear war by mistake. Because ICBMs are vulnerable to attack (they sit in fixed silos in the ground, and Russia knows exactly where they are), they are kept on high alert at all times to enable their launch within minutes. In the case of a false alarm, a president would be under great pressure to “use them or lose them” and launch our own missiles before a possible attack arrives.

False alarms have happened multiple times, and in an era of cyberattacks on US command-and-control systems, the danger has only grown. Starting a nuclear war by mistake is the greatest existential risk to the United States today. The ICBMs are, at best, extra insurance that we do not need; at worst, they are a nuclear catastrophe waiting to happen.

Scrapping the ICBMs would reduce the US triad of silo-based ICBMs, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and nuclear bombers to a dyad.

The warheads on the ICBMs represent about one-quarter of US deployed strategic warheads. More than half of deployed US strategic warheads are mounted on submarine-launched missiles, and the remainder are nuclear bombs and warheads on air-launched cruise missiles in storage bunkers at the three US strategic bomber bases.

The total number of deployed warheads could be maintained by deploying an additional 400 warheads to US ballistic-missile submarines. That might not be necessary, however, since the DOD’s 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States concluded that the US could “maintain a strong and credible strategic deterrent while safely pursuing up to a one-third reduction in deployed nuclear weapons from the level established in the New START Treaty.”

The New START level is 1,550 deployed warheads, counting the approximately 60 deployed US nuclear-capable bombers as carrying one warhead each.

Since a large fraction of US and Russian nuclear weapons are targeted on each other, it is possible that, by eliminating about 500 silos and launch-control centers as targets for Russia’s ballistic missiles, the US could make it easier for Russia to agree to further cuts.

Survivability of US ballistic missile submarines. The strength of the argument to eliminate the land-based ICBMs hangs principally on the survivability of US ballistic missile submarines at sea. If those could be destroyed, then the only way to preserve the survivability of the US deterrent would be to put both the ICBMs and the nuclear bombers in a launch-on-warning posture. According to the DOD’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, however, “When on patrol, SSBNs are, at present, virtually undetectable, and there are no known, near-term credible threats to the survivability of the SSBN force.”

The range of US submarine-launched ballistic missiles is so great that, even with a full load of eight W76 warheads, they can reach their targets from just off their bases in Kings Bay, Georgia and Bangor, Washington. They therefore can hide almost anywhere within the vastnesses of the North Atlantic and North Pacific Oceans.

Unlike radar, which can detect tiny reflected signals from incoming warheads thousands of kilometers out in space, radar’s underwater counterpart, active sonar, has an effective range of only tens of kilometers. Sound beams bend in the ocean because of its temperature and density gradients and reverbate off its bottom, merchant ships, schools of fish, and decoys.

The only proven way to detect submarines at a distance is through passive sonar, listening for and tuning in on the distinctive frequencies emitted by a submarine’s internal machinery and by its propellors. During the Cold War, however, the US Navy made huge investments in quieting its submarines by putting sound absorbers between the machinery and their hulls. More recently, it has been switching from propellors to pumps for propulsion. US submarines became so undetectable by Russian submarines, even close up, that in 1993, a Russian ballistic missile submarine, not knowing that it was being tracked by a quiet US attack submarine, turned in front of the US submarine, causing a collision.

An alternative approach to locating a US ballistic missile submarine would be to try to pick it up as it exits its base and trail it. The US Navy is interested in this possibility and has openly discussed using unmanned surface vehicles to track other nations’ submarines. US ballistic missile submarines are subject to “de-lousing” procedures to deal with possible trailing submarines when they head out on their missions. The Biden administration should check, however, that de-lousing covers all the possibilities—perhaps with an outside review of the Navy’s anti-submarine-warfare and countermeasures work by an expert group of technical consultants such as the JASONs.

At any one time, eight to 10 of the 14 US Ohio–class ballistic missile submarines are at sea in the Pacific and Atlantic, two are in overhaul, and the remaining two to four are in port for supplies and a change of crews. The 20 Trident II missiles on each Ohio-class submarine can carry up to eight warheads each, for a total of up to 160 warheads per submarine. The missiles carry about half that many on average today, however, because of the New START limits on total deployed warheads. The United States therefore has 600 to 800 submarine-launched ballistic missile warheads untargetable at sea at all times. About half are in deployment areas, with the submarines cruising slowly near the surface with their missiles launch ready and their radio antennas and satellite signal receivers deployed. The other half are in transit at higher speeds to or from their deployment areas with their missiles not launch ready. The nuclear weapons in transit are considered a survivable reserve.

Starting in 2028, the Navy plans to replace its 14 ballistic missile submarines with 12 new Columbia–class submarines initially carrying 16 Trident II missiles each. The Navy argues that, because the new submarines will have lifetime reactor cores and therefore will not require lengthy mid-life refueling outages, it will be possible to keep about the same minimum number of submarines at sea as today.

The duration of a standard US ballistic missile submarine patrol is 70 days, but patrols have been extended to up to twice that length—140 days—when maintenance problems delayed deployment of a follow-on submarine.

Because they do not need to be refueled and they produce their own fresh air and water, the nuclear submarines could stay at sea for years if stocked with sufficient food. The guidance for backpackers, who do more physical work than a submarine crew on average, is to carry about 1 kilogram of food per day. For a crew of 155, that would be about 60 metric tons per year—not much for a ship with a displacement of about 20,000 tons. For emergency supplies, the US Navy has recently demonstrated replenishment by multiple air-delivery means (parachute, helicopter, and drone).

Bombers. If the ICBMs were retired, the other remaining leg of the triad would be bombers. Long-range bombers were the first US strategic nuclear weapon delivery vehicles. With the advent of Soviet ICBMs in the 1960s, Strategic Air Command, which subsequently merged into Strategic Command, became concerned about the vulnerability of its bomber bases to missile attack. It therefore kept some of its bombers, loaded with multimegaton bombs, aloft at all times. In 1968, after a few crashes, this practice was abandoned as too dangerous. By then, the Minuteman missile silos had been built. The silos were relatively invulnerable because of the poor accuracy of the ballistic missiles of the time. For the remainder of the Cold War, a fraction of the bombers were kept loaded and on “strip alert,” ready to take off within 10 minutes of warning. With the end of Cold War, the bombers were taken off alert but could be returned to that posture in a crisis. They and their aerial refueling “tankers” also could be dispersed to many airports.

In the 1980s, to deal with improving Soviet air defenses, US B-52 bombers were equipped with long-range (2,400-km) air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs), which could be fired from beyond the range of air defenses. Each B-52 can carry up to 20. In the 2030s, the ALCMs are to be succeeded by stealthy long-range standoff cruise missiles.

In addition, the Defense Department proposes to buy at least 100 new B-21 bombers, starting in the mid-to-late 2020s. The B-21 will have improved stealth capabilities for penetrating upgraded Russian and Chinese air defenses, but will also be able to carry the long-range standoff cruise missiles as well as bombs. Like the current B-2 and B52H nuclear bombers, the B-21 would be available for non-nuclear missions. In fact, the plan is for the B-21s to replace the remaining 63 B-1 bombers, built in the 1980s and now equipped only for non-nuclear missions. They also would replace the 20 B-2 stealth bombers, mostly produced in the 1990s. Some or all of the 46 older B-52Hs that are equipped to carry long-range nuclear cruise missiles might be retained, however. They were built during the 1950s and are two decades older than the Minuteman III, but, like the Minuteman IIIs, they have had most of their parts replaced in cycles of refurbishment.

Life-extend the Minuteman III? It could take years for Congress to decide whether or not continued deployment of ICBMs is in the national interest. It is important not to preempt the debate by making a premature commitment to the production of the new ICBMs. (A commitment to the necessary design work has already been made.)

Fortunately, the time necessary for debate can be made available by preparing to life-extend the Minuteman III missiles instead of replacing them. The expiration of the Minuteman III ICBM is determined primarily by the life of its solid fuel and its guidance system, both of which can be replaced, as has already been done once. The missiles were first deployed around 1970 and were refurbished 30 years later. They could be refurbished again starting around 2030 for a small fraction of the cost of the new missiles. In 2014, RAND estimated the cost of refurbishing 420 Minuteman IIIs at $20 to $40 billion

Recently, nuclear weapons experts Steve Fetter and Kingston Reif suggested that the longevity of the current Minuteman IIIs might be extended without refueling if non-destructive tests could be devised to measure the actual condition of the fuel. They believe the Air Force may have been overly conservative in its assumed longevity of the fuel. The boosters of retired Minuteman IIs, whose first and second stages were almost identical to those of the Minuteman III, have proven highly reliable for satellite launches.

The remaining issue is whether there are enough Minuteman IIIs left. The missiles are being expended in flight tests at an average rate of 4.5 launches per year—up from a previous rate of three per year. There were 500 missiles in inventory in 2017. If the current testing rate were maintained, the number of missiles would not fall below the currently deployed 400 until 2039, and below 300 until after 2060. If the testing rate were returned to three per year, the number of missiles would not drop below 400 until 2050.

There is therefore no reason to rush to build a new ICBM.

A practical recommendation. The US Minuteman III ICBMs should not be replaced. Eight Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines at sea, each carrying up to 128 warheads—backed up in a crisis if necessary by a re-alerted strategic bomber force—would constitute a more than adequate US nuclear deterrent under any plausible circumstances. Congress could give itself more time to debate this option by authorizing planning for life extension of the current Minuteman III ICBMs starting around 2030.

No comments:

Post a Comment