Zaynab El Bernoussi

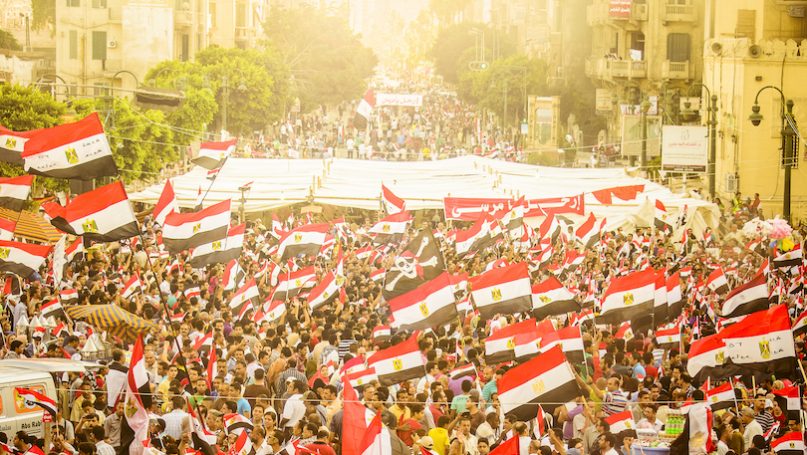

About ten years ago, I was a younger Arab graduate student in Queens Astoria experiencing the unfolding of the Arab Uprisings. I was catching rumors that it would start in Morocco. I was primarily worried for my parents there and, maybe in an Arab fashion, I imagined the worse happening and I was struck by the guilt of being far away and not able to protect my progenitors. I felt an obligation to go back and I did. I felt that my world was crumbling before me. Ten years on, the earth is still spinning, and life has continued. In this attempt to commemorate ten years since the Arab Uprisings and the marking 2011 revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt that sent lasting shockwaves in my region, I want to spend a bit of time on a dignity lesson from the Arab world to the rest of it. This dignity lesson is about a need to develop political institutions, empower the youth and expand their share of the economy, and, finally, accept diversities at last.

Before the lesson, I would like to quickly reassert the importance of talking about the ‘Arab Uprisings’ as opposed to the widely used counterpart ‘Arab Spring’. The Arab Spring makes a connection to the 1848 Spring of Nations in Europe, which were popular uprisings against old monarchical rulings. The problem with this connection is that it continues an orientalist tradition of likening the East to a so-called more advanced West. This creates an arbitrary symbolic power structure, at the very least. On the other hand, talking about the Arab Uprisings makes more sense for the immediate timeline of 2011 in the region because it makes a connection with the 1987 Intifada in which Palestinians rose to Israeli state violence in a series of protests which were mostly suppressed. Very similar to the 2011 events. The Palestinian uprisings were not alone, there was also before them the Berber Spring in Algeria and one can keep going earlier.

Another starting point for this motion of the Arab Uprisings is what has been coined the tragedy of the Arabs, with Arab not being an ethnic denominator but a describing feature of the dominant mode of communication that unites and integrates the region. This Arab tragedy have reemerged in different times since the postcolonial era when intellectuals inside and outside the region wondered about what went wrong with an Arab leadership of the world almost seven centuries ago. Actually, the region, since millennia ago, has known long histories of vibrant communities that have managed to live together, but it seems that since the postcolonial era they have been struggling to relearn to live together.

First, regarding the Arab uprisings dignity’s lesson for political institutions. Since their inception, today’s Arab states have ruled in a fashion of “us or chaos” that has become, one can argue, a trademark of the modern state development and even the ideal of democracy. Indeed, statism is established on hierarchical structures of power that are inevitably violent and create a conundrum for the development of human rights around the world. Indeed, it is difficult to both accept authority and uphold principles of equality because it becomes unclear if all human lives have the same worth. This question is particularly resonant today in a time when our world is fighting a pandemic. The Arab Uprisings are a lesson of dignity because it triggered the need for political institutions to recognize human worth. It is fundamental that we fight for every life, not only one’s family, one’s country, or one’s religion. And when lost lives were not fought for, we must at least recognize the wrong, which helps right it and build trust, and trust is a necessary ingredient to relearn to live together.

Second, regarding the Arab uprisings dignity’s lesson for empowering the youth. The youth are important for our economies around the world. I teach young people and what I see in them is a tremendous energy that we often, as educators attempt to discipline and punish. There is a commodification of the youth into students, recruits, workers and by the time they roll out of their young age, they become the new steerers of the wheel. The youth are told to shut up, to speak, to act, and to stop, and that is a lot of mixed messages that we need to clarify in their ambivalence with better communicating. Most importantly, young people’s value is often diminished by the smaller contribution they are left with in the economy and that shouldn’t be how we value them because of the intrinsic dimension of human worth. The youth in the Arab region continue to be victims of higher rates of unemployment and that is an ongoing grievance that needs heeding. The youth are an easy target of marginalization and there are many other groups that can take up such position. Revolutions mount to prophetic moments for the marginalized. We need to learn from revolutions, not to try to abort them, but to try and emancipate those at the margins for a better living together.

Lastly, regarding the Arab uprisings dignity’s lesson for accepting diversities. Postcolonial theory in different disciplines of social sciences and the humanities has paved the way for studies that challenge what has been coined epistemological imperialism or a hegemony of knowledge production mostly from Western-based and Western-influenced scholarship. Despite the waves of decolonization in the world over a century ago, the colonial discourse based on that very epistemological imperialism seem to continue because we keep seeing dichotomies of the better/developed/whiter/male versus the worse/underdeveloped/darker/female. The issue with this epistemological approach is creating an imbalance in power structures by which violence against the weaker becomes normalized and, again, that is another limit to accepting intrinsic human worth. In a globalizing world, we cannot afford stigmatizing the other and rejecting diversity because it is not sustainable for a more dignified world in which the worth of everyone and everything is recognized to better live together.

To conclude, ten years since the Arab uprisings is still too little time to appreciate the changes of those marking events in which lives were lost fighting for us today. Let’s dignify their memory.

No comments:

Post a Comment