Bruno Philip

China, with its propensity to cover up the truth, has reacted with surreal moderation to the coup d'état perpetrated on Feb. 1 by the Myanmar army. Global Times, the English-language daily paper of the Chinese Communist Party, simply described it as "a majorministerial reshuffle."

Earlier, immediately after the coup, the spokesman for the Foreign Ministry of the People's Republic of China, Wang Wenbin, issued a more terse but significant diplomatic statement: "All concerned parties in Myanmar should settle their differences" in order to "maintain social and political stability."

Here's the reality behind this hollow statement: Everything that happens in Myanmar, which has an extensive border with China, is of paramount importance in the eyes of Beijing. For China, political stability in Myanmar is essential to guarantee China's economic investments in the country will continue without hindrance. What do the rulers of the Forbidden City hate most of all? Unexpected, sudden changes — even if it is possible that Beijing had been informed in advance of this "reshuffle."

For both nations, geopolitical imperatives and economic necessities are combined in the framework of a complex, strategically important and longstanding Sino-Myanmar relationship.

But who benefits from the coup? How will China be able to best protect its interests at the dawn of this new age in Myanmar's turbulent history? Will China benefit from the military returning to the forefront, if only because this event symbolizes a setback in the United States' Asian policy? Since the Obama era, this policy has been dependent on a strategy of supporting democratic countries that can balance the rise of China in the Asia-Pacific region.

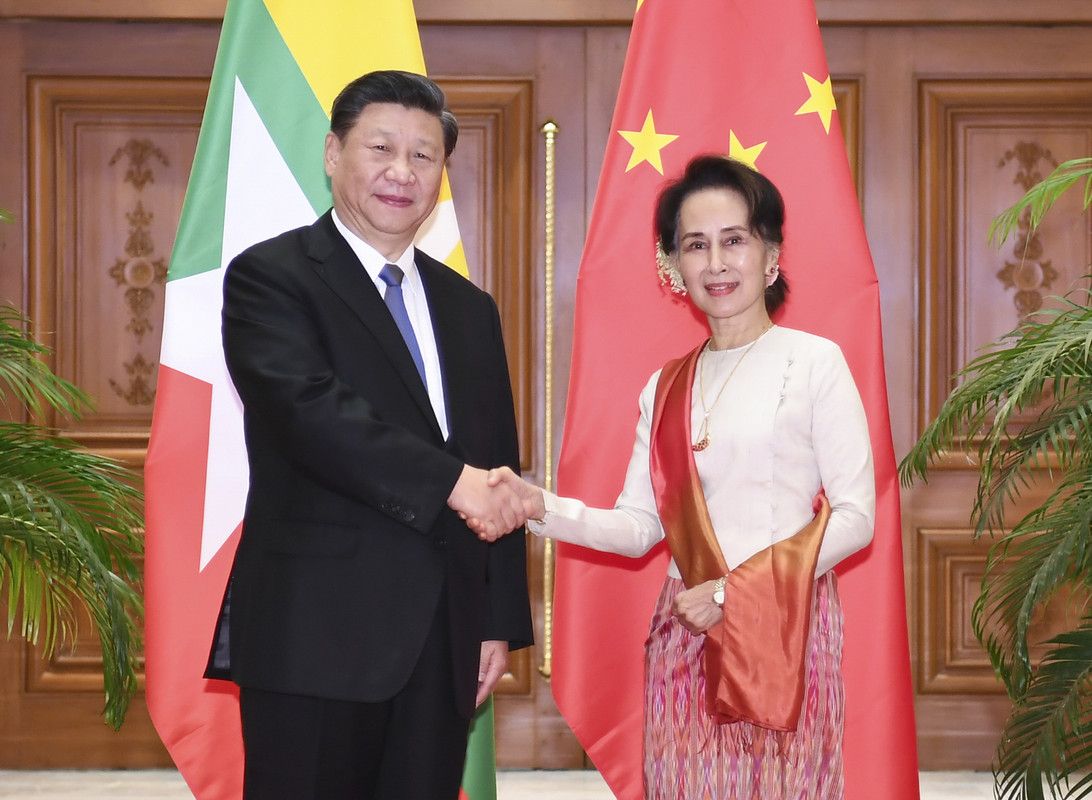

Up to this point, Beijing had been courting Aung San Suu Kyi, the former dissident who became the leader of Myanmar. This courtship caused General Min Aung Hlaing, the leader of the Feb. 1 coup, to worry about Beijing's persistent double dealing: China needs to guarantee a solid relationship with any Myanmar leader, but there is always an "at the same time" clause in its strategy because the Middle Kingdom always keeps two irons in the fire.

A more democratic Myanmar would provoke an ideological conflict with China.

Presenting itself as a friend and ally of Myanmar, China, out of its own self-interest, arms several ethnic guerrillas who fight against Myanmar's army and whose rear bases are located on the Chinese border. This allows Beijing to present itself as a "peacemaker" and a key interlocutor in the peace process — so far unproductive — between these guerrillas and Myanmar's government.

In 2017, Aung San Suu Kyi went to Beijing where she formally announced Myanmar's participation in China's famous "New Silk Roads" program. The two countries then signed an agreement to develop the "China-Myanmar Economic Corridor," which is intended to strengthen Sino-Myanmar cooperation.

On the ground, these initiatives took the form of major infrastructure projects, such as the construction of a new main road from the border town of Muse to Mandalay, Myanmar's second largest city. There was also the building of a deep-water port in Kyaukpyu, on the Bay of Bengal, an area that already serves as an oil and gas terminal for the pipelines supplying China's Yunnan province. This enables the Chinese to receive Myanmar's offshore gas and oil directly from the Indian Ocean without making the long detour through the Strait of Malacca to reach Shanghai, Tianjin or other ports on the Pacific coast. Significantly, this strait could be obstructed in the event of a conflict between Beijing and Taiwan.

Xi Jinping with Aung San Suu Kyi in January 2020 — Photo: Xie Huanchi/Xinhua via ZUMA Wire

Since 2015, however, Myanmar has been actively expanding its ties with Western countries in addition to those it already had with Japan, Thailand and Singapore. It has also managed to reduce its debt to China by 26%, even though the People's Republic of China remains its main trading partner.

A former professor of political science at Tsinghua University in Beijing, Wu Qiang, argued in an interview with Radio Free Asia that the coup could ultimately prove to be a good deal for Beijing. "If Myanmar had continued on the path to democracy under the leadership of [Aung San Suu Kyi], its foreign policy might have moved in the direction of strengthening ties with Washington. And for now, there is no conflict between Myanmar and China in terms of economic interests. On the other hand, a more democratic Myanmar would provoke an ideological conflict with China."

Aung San Suu Kyi had tried to maintain a cordial relationship with the leader of China, President Xi Jinping. In the West, she has been totally discredited for her inaction following the torture and massacre of tens of thousands of members of the Rohingya minority. More than seven hundred thousand Rohingya refugees have since fled to Bangladesh.

The 'men in green' have a de facto ally.

The impassable constraint of the realities of the diplomatic doctrine of any great power should lead China to support the leadership in place, because that is in its interest. This makes it unlikely that Beijing will provoke tensions with the new military administration in the name of a haphazard defense of Aung San Suu Kyi.

During the last years of dictatorship at the beginning of this century, the leaders of the Tatmadaw, Myanmar's armed forces, felt it was time to open the country up in an attempt to free itself from China's stifling embrace — and to lower the level of dependence on their neighbor. Such unfaltering nationalism, however, risks complicating the relationship between Beijing and Naypyidaw (Myanmar's capital). And the "men in green" of Myanmar's military have already found a de facto ally in China. The gesticulations of Washington and European countries may not end up changing this relationship much.

No comments:

Post a Comment