Brendan McCord and Zoe A. Y. Weinberg

Technology is fundamentally altering the security landscape. Rapid and profound advances in hardware and software, paired with the global shift to digitally networked communications and transactions, have transformed the economic and security landscape, along with the fabric and rhythm of daily life. They have introduced new risks to personal safety and national security, fueled a strategic competition between the United States and China, and increased collective vulnerability to malicious actors armed with cheaper, more effective, and difficult-to-attribute tools.

These changes require the U.S. government to better incorporate emerging technology issues in its national-security decision making—particularly by overhauling the institutional structure and priorities of the National Security Council, which sets the stage for government’s approach to national security. Drawing from more than 25 interviews with current and former NSC staffers, interagency personnel, national security professionals, policymakers, and academics, this analysis offers several policy options for restructuring the NSC to better respond to developments in conflict. Interviewees represented a diverse array of perspectives, with strong and differing opinions on every issue. Our research sought to surface the best ideas and to probe key concerns, while recognizing that not all trade-offs will be satisfyingly balanced, nor disagreements resolved. This analysis serves as both a snapshot of the current challenges faced by our national security enterprise and a blueprint for thinking through how to solve them.

The outset of the Biden administration offers a remarkable opportunity to reform the NSC. The new policymakers in the White House have two broad-strokes options for better incorporating emerging technology into security coordination: 1) an NSC-based strategy that adapts the council’s structure to take on emerging technology issues; or 2) an agency-centered approach that requires across-the-board changes throughout the executive branch.

The first option would mean filling the NSC with world-class staff, including many individuals well-known in Washington and drawn from talent pools where expertise and webs of network effects offer immediate fluency, trust, and credibility. It would mean bolstering the technical expertise on the NSC and creating dedicated structures and posts focused on the threats posed by technology. The Biden administration has already initiated some of these changes. This strategy is likely to work. But could the administration go further?

The second model is an agency-based structure. If adopted maximally, this approach would de-layer the NSC and deploy the majority of its technology talent into the agencies. NSC experts would deploy in supporting roles to leadership offices in government agencies. Such an approach would allow for ground-up coordination and improve connectivity between the NSC and the agencies, enabling the administration to set priorities and infuse all of government with technological insight and risk-awareness. While it is swifter to enact reform at the White House level, the long-term payoff of the more challenging whole-of-government reorientation may be worth the greater difficulty and effort. If successful, these reforms should result in a smaller, nimbler, and more effective NSC. Agency-centered reforms will outlast a single administration and will position the United States for long-term competitiveness.

The changing face of security

Technology has long played a part in defining the security landscape, and as technology has evolved, so too has the job of national security policymakers. They have always had to take stock of their approach, reexamine existing theories and practices of warfare, and determine how organizations and strategies ought to adapt in light of new tools. Recent technological breakthroughs in fields as varied as artificial intelligence, machine learning, hypersonics, synthetic biology, and fifth generation cellular networks have only accelerated the pace of change. These breakthroughs have consequences for U.S. economic competitiveness, but also threaten to dissolve the mortar in the bricks of the current U.S. national security apparatus.

While technological developments have always shaped the nature of global threats and the evolution of the security landscape, the scale, velocity, and potential impact of emerging technology is unprecedented. Many of the challenges we face today are not only facilitated by advances in technology—such as developments in weapons capabilities or shifts in the underlying geopolitical balance of power—but present new risks in and of themselves, as in the case of information operations, cyberattacks, or genetically engineered biological threats.

Furthermore, the pace of evolution today is faster than ever before. In the past, a technological breakthrough was often followed by a period of relative stability, giving policymakers and regulators a chance to play catch-up in developing new rules of the road. Today, techniques and methods associated with certain technologies—for example, natural language processing—are rapidly and constantly evolving, making it particularly difficult for policymakers to master an area of expertise.

In addition, many present-day innovations are “born open” rather than “born secret.” In the past, major advances in military technology were generated in government labs or under government direction and were classified in nature—hence the “born secret” designation. By contrast, recent innovations in areas such as machine learning are available on open-source platforms from day one. Their access has become largely democratized, with potent technologies available to almost anyone with a computer and internet connection.

Geopolitical competition is evolving in response. The character of military and economic rivalry is shifting so profoundly that our old tools for understanding and fighting appear increasingly misaligned with the new reality of global competition. As an example of the novelty in contemporary geopolitical competition, consider the fact that the United States and China are currently jockeying over which country will control a global social media platform. Such changes are here to stay, and future hostilities are likely to take the shape of information operations, intellectual property theft, cyberattacks, and the undermining of democratic institutions. The new security landscape is particularly expedient to adversaries who benefit from certain asymmetric advantages—such as quantities of data, demographic trends, and autocratic control over information flow—creating an environment ever more hospitable to authoritarian ideology and regimes.

An opportunity for upgrade

Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. national security policy and the NSC’s role in it has rested on a series of assumptions about how conflicts unfold, the relevance of geographic clustering, an emphasis on great power politics and defense spending as an indicator of military might, and a limited role for commercial or open-source innovation. Since the NSC’s structure reflects those assumptions, it is not well-suited for the cross-sectoral, transnational nature of new threats enabled by emerging technology. The complexity and unique character of these challenges warrant a rigorous re-evaluation of the existing structures that comprise the U.S. security apparatus and, in particular, the National Security Council (NSC).

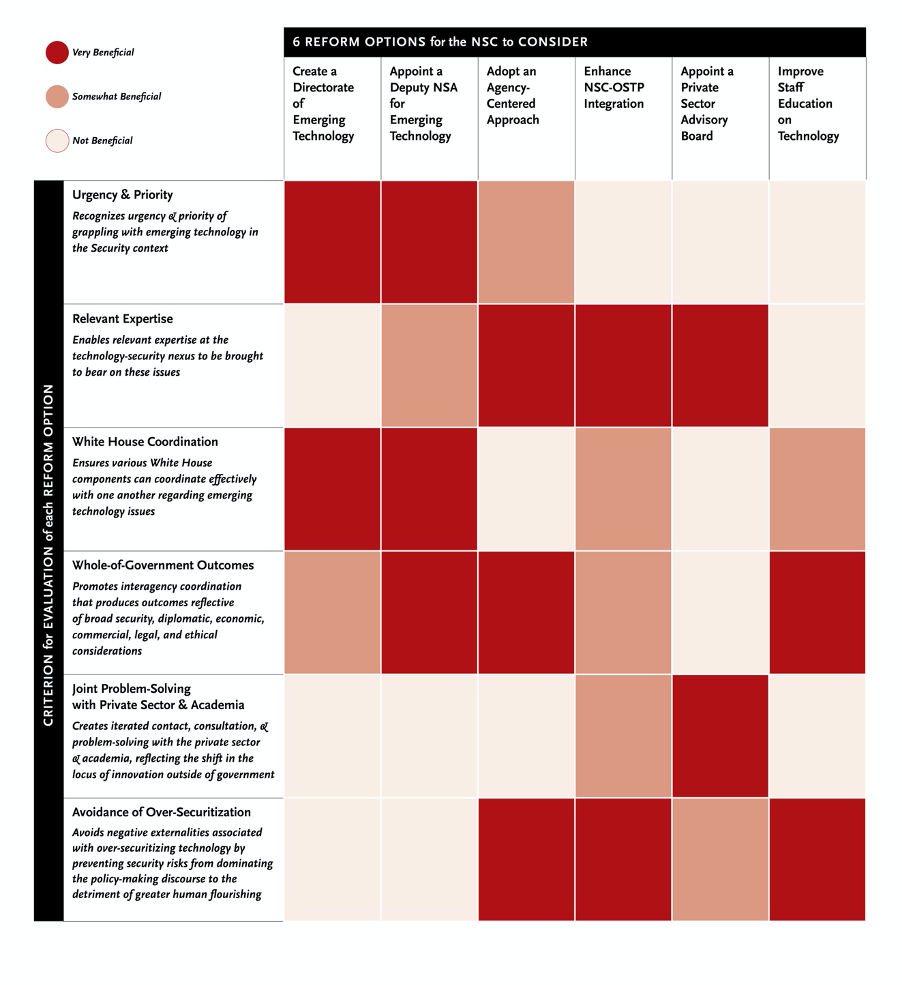

An ideal reform option would satisfy the following criteria:

Recognizes the urgency and priority of grappling with emerging technology in the security context;

Enables relevant expertise at the technology-security nexus be brought to bear on these issues;

Ensures various White House components can coordinate effectively with one another regarding emerging technology issues;

Promotes interagency coordination that produces outcomes reflective of broad security, diplomatic, economic, commercial, legal, and ethical considerations;

Creates iterated contact, consultation, and problem solving with the private sector and academia, reflecting the shift in the locus of innovation outside of government;

Avoids negative externalities associated with over-securitizing technology by preventing security risks from dominating the policy-making discourse to the detriment of greater human flourishing.

Reform option 1: NSC-based approach

By making targeted structural changes to the NSC’s organization, including the creation of an Emerging Technology Directorate and the appointment of a deputy national security advisor, the council can be reoriented to better address emerging technology. The creation of a new position—deputy assistant to the president and deputy national security advisor for technology—would help to elevate emerging technology threats within the White House and in the national security establishment. The right candidate would be a polymath with the technical expertise to secure credibility among technologists and the ability to cover a wide range of security issues and balance competing priorities. These reforms would signal to the rest of government and industry partners that emerging technology security issues are a key priority with commensurate resources and talent dedicated to addressing them. This new position would oversee at least two directorates: the existing Cyber Directorate and the new Emerging Technology Directorate. Oversight of these two directorates ought to provide the new deputy muscle and influence in the White House.

The creation of the Emerging Technology Directorate would address the NSC’s historically inconsistent coverage of emerging technology issues, which have been divvied up among the Cyber Directorate and other directorates (often Defense Policy or Strategic Planning) and resulted in a lack of a coherent strategy. This new directorate would house several directors covering a range of threats arising from innovation and prevent tech-related threats from falling between the cracks. The directorate would be structured to ensure consistency in mission and scope, undertake regular reviews to adjust coverage and expertise to respond to a constantly evolving landscape, and engage in constant horizon-scanning for new risks, in addition to taking on ad hoc topics as necessary. The directorate would lead Interagency Policy Committees (IPCs)/Policy Coordinating Committees (PCCs) below the deputies level, and coordinate its activities with the Technology Policy Task Force at the Office of Science and Technology Policy and other relevant White House offices.

The creation of this new technology-focused directorate would require coordinating with other White House bodies working on the issue. Several staff members within the Emerging Technology Directorate ought to be “dual-hatted” between the NSC and the National Economic Council and others dual-hatted between the NSC and OSTP, with reporting lines to principals in both entities. Dual-hatting staff would ensure that security policy would be informed by both science policy and economic concerns. (A similar structure has worked successfully for the Directorate of International Economic Affairs, known as “Intecon.”) The DAP-level position could also have a formal appointment within OSTP, to help facilitate coordination between the two. Dual-hatting with the NEC is especially useful for technology issues that have significant economic considerations, such as export controls and supply chains. It would also prevent emerging technology issues from being “over-securitized,” with an outsize emphasis on national security at the expense of economic concerns. While dual-hatting can create bureaucratic convolution and at times impede the ability of teams to move quickly, it also helps to eliminate the possibility of redundancies between councils, which may be meaningful in limiting the growth of staff.

Of course, creating an Emerging Technology Directorate introduces complications, including the challenge of cleanly defining the scope and proper coverage of the group. Grouping threats under the broad title “emerging technology” is in many ways a clumsy designation and belies the reality that these issues are deeply intertwined with other domain-specific or regional threats. For example, the threat of information operations cannot be tackled in a vacuum. Specific disinformation campaigns stem from regional dynamics that may already be well-covered by existing NSC directorates. In addition, some security issues that may rightly fall into this directorate’s scope are perhaps more properly understood as “emerging threats” arising from the use of technology that itself may not be particularly novel.

The disadvantages of creating a new deputy includes the possibility that yet-another deputy national security advisor would increase bureaucratic processes, strain the national security advisor’s attention, and result in additional and unnecessary meetings. Some argue that the position is simply unwarranted, or that another position—the deputy national security advisor for transnational issues—should be resurrected instead, as many emerging technology threats are indeed transnational in nature. It is worth noting that there may be good reason to do both—create a new deputy position and resurrect transnational threats—as there are a number of transnational topics that fall into the bucket of the latter but not the former, including pandemics, climate change, and the refugee crisis. Other issues remain unsettled, such as whether proposals to create a Space Directorate and a Telecommunications and Supply Chain Directorate ought to fall under the authority of the new deputy.

Reform option 2: an agency-centered approach

Another strategy for incorporating emerging technology into security decision-making involves a comprehensive restructuring that locates expertise across the executive branch, with the NSC occupying a supporting role rather than taking the lead.

Under this decentralized approach, the center of gravity on a given issue would reside in specific departments and agencies with relevant expertise. The national security advisor may choose to appoint an advisor or coordinator to convene government voices on emerging technology, but this person would not have extensive dedicated staff nor seek to drive policy from the NSC. For example, the National Science Foundation might serve as the lead for new research and development efforts on security-related technology. If implemented maximally, this approach would cause the NSC to embed within the top offices of every element of the executive branch to help coordinate from that position. It may also require strengthening and empowering existing tech policy offices to cover security-related subjects more effectively. For example, OSTP staff might need to be cleared in order to run point on certain sensitive policy areas.

An agency-centered approach would rely on bottom-up evolution at the department and agency level. The Department of Defense is the furthest ahead in accounting for the role of emerging technology, with the establishment of the Defense Innovation Unit, the Defense Digital Service, and the Joint AI Center. But efforts to integrate DoD’s contribution to the interagency process on policy remains underdeveloped, and the Office of Net Assessment and the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy could be better utilized in this regard.

In the intelligence community, evolution may mean strengthening existing capacity by increasing the number of technologists in its analyst ranks. At the Departments of Commerce and Treasury, development of advanced market forecasting on the technology sector may be a worthwhile investment. The State Department will need to upgrade its diplomatic strategy to structure the types of global alliances and multilateral architectures needed to successfully engineer technological statecraft for the next century (such as the proposed D-10 or T-12).

There are several key benefits to the agency-centered approach. First, it takes advantage of the fact that most subject-matter expertise naturally resides within departments and agencies and enhances their ability to assume leadership roles on those policy areas. Limiting the NSC to a minimalist role may also help to prevent NSC-overreach and proliferation of staff. The agency-centered approach, while posing a more complex bureaucratic undertaking up front, may also bring about much-needed changes across departments and agencies that will ultimately be necessary in the long-term.

There are also disadvantages to removing the center of power from the NSC. In a memo evaluating tech policy issues at the NSC, former Senior Director for Strategic Planning Christopher Kirchhoff noted that “the U.S. cannot rely on any one department to lead the U.S. response to them, given their security, diplomatic, economic, commercial, legal, and ethical implications.” Only the NSC has the vantage point that enables it to holistically consider the myriad trade-offs and competing interests across the executive branch. And without a dedicated NSC entity focused on emerging technology, resources and attention may be diverted from adjacent NSC directorates, such as Cyber, Defense, or Strategic Planning. In order for the NSC to play an effective role as a convener and address all of these facets, “the NSC will need dedicated capacity to drive an integrated [U.S. government] approach,” Kirchhoff argued.

A holistic reassessment

Throughout history, policymakers have suffered from a form of continuity bias, failing to appreciate paradigm shifts, underweighting looming threats, and over-indexing on past experiences. Today we find ourselves in one of those moments. Technological innovation has been an exceptional source of American progress and vitality, but it may also be its Achilles heel. The security landscape is evolving so rapidly and unexpectedly, the institutions we trust to protect us are struggling to keep up.

The time has come for a holistic and comprehensive reassessment of the NSC’s handling of emerging technology. The start of a new administration provides a unique opportunity to reconceive the NSC, and in turn, to establish a strong framework for securing America’s future.

Brendan McCord is a technology entrepreneur and a former HQE/SGE at the Department of Defense, where he was an author of the Department of Defense Artificial Intelligence Strategy, founder of the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, and head of Machine Learning at Defense Innovation Unit. He is an adjunct senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security and a member of the advisory board of SAP National Security Services and Applied Intuition.

Zoe A. Y. Weinberg is a fellow at Schmidt Futures focused on geopolitics and previously worked on ethics and policy issues at the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence and Google AI.

The authors would like to thank the following individuals for offering their insight and perspectives to this report: David Agronovitch, Salman Ahmed, Tess Bridgeman, Tarun Chhabra, David Cohen, Ivo Daalder, R. David Edelman, John Gans, Andrew Grotto, Avril Haines, William Happer, Colin Kahl, Thomas Kalil, Christopher Kirchhoff, Amb. Michael McFaul, Gen. H. R. McMaster, Chris Meserole, Jeffrey Prescott, Nadia Schadlow, Paul Scharre, Michael Sekora, Matthew Spence, Isaac Taylor, Anthony Vinci, Sec. Robert Work, and Amy Zegart.

Google provides financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

No comments:

Post a Comment