BY ROBERT D. KAPLAN

Realism in foreign policy reflects a messy, dangerous world where too little can be distilled into clear-cut moral absolutes, and thus national interest takes precedence over universal values. Nevertheless, a world ravaged by war, migration, refugee flows, and a demand for dignity across ethnic, religious, and racial lines requires a morally sustainable foreign policy rooted in idealism. Yet realism and idealism can work together. The American diplomatic tradition at its best has employed humanitarianism as a complement to power politics; not as an opponent of it. This all has profound consequences for our great power competition with China and Russia today, and for how the Biden Administration will deal with it.

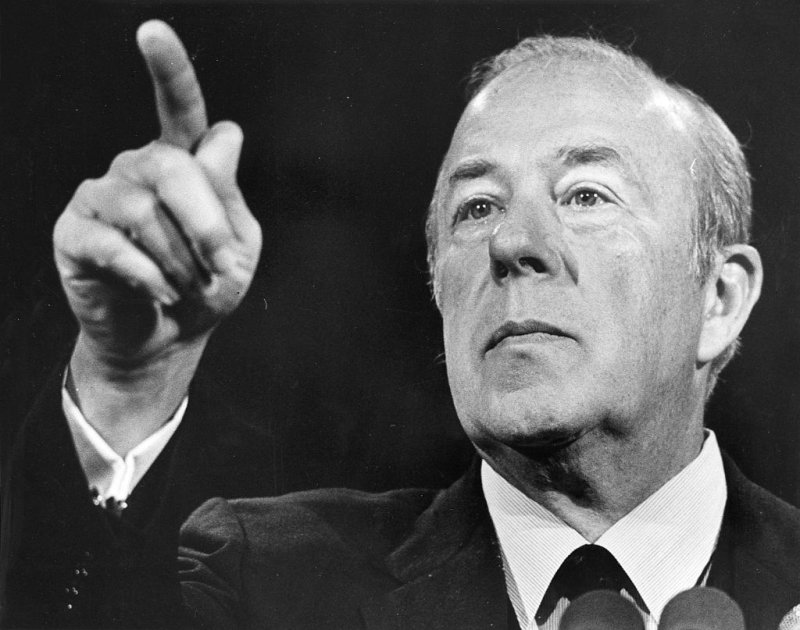

Realism in foreign policy reflects a messy, dangerous world where too little can be distilled into clear-cut moral absolutes, and thus national interest takes precedence over universal values. Nevertheless, a world ravaged by war, migration, refugee flows, and a demand for dignity across ethnic, religious, and racial lines requires a morally sustainable foreign policy rooted in idealism. Yet realism and idealism can work together. The American diplomatic tradition at its best has employed humanitarianism as a complement to power politics; not as an opponent of it. This all has profound consequences for our great power competition with China and Russia today, and for how the Biden Administration will deal with it.Some of the darkest days of the Cold War—governed by realpolitik calculations of power—were also suffused with human rights concerns at the highest official levels. It was what defined the American brand and distinguished it from that of the Soviets. The State Department’s Refugee Bureau had its beginnings under President Jimmy Carter, when Communist takeovers in Vietnam and Cambodia led to a humanitarian cataclysm, as millions streamed out of those countries into Thailand. President Ronald Reagan picked up Carter’s torch, with Reagan’s secretary of state, the late George Shultz, who died on Feb. 7, seamlessly combining hard-headed realism with humanitarianism, especially throughout Africa. I know I was there as a reporter for The Atlantic.

The Shultz State Department exposed the Ugandan regime in 1984 for its mass murder and starvation of over 100,000 civilians in the “Luwero Triangle” region, which helped lead to a better regime coming to power there and amplifying America’s influence in East Africa. Shultz’s diplomatic team took the lead in emergency aid to ethnic Eritrean and Tigrean civilians pouring out of famine-wracked Marxist Ethiopia in 1985. In 1988, Shultz denied anti-communist RENAMO guerrillas in Mozambique aid under the Reagan Doctrine, because of RENAMO’s gross human rights crimes: it was a key turning point in ending the Mozambican civil war that would save hundreds of thousands of lives and play a pivotal role in a transition to a post-apartheid southern Africa.

Shultz’s actions were part of a larger story. The fact that we were in a world-wide geopolitical competition with the Soviet Union gave us a naked self-interest in engagement with virtually every country in the developing world. The highwater mark of the U. S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the State Department’s humanitarian arm, was during the Cold War, when it had intensive foreign aid programs in many dozens of countries. But it was George Shultz in particular, such an uncharismatic and easily forgotten secretary of state—yet an extraordinary leader of organizations—who most effortlessly joined idealism together with realism in the last and most pivotal decade of the Cold War. The toppling of Communist regimes in 1989 was the culmination of a global strategy, headlined by the Helsinki process in Europe, that was rooted in both hard power and human rights.

Shultz, like other successful secretaries of state, understood that the foreign policy of a world power constitutes a hierarchy of needs, and moral action must take its place in that hierarchy to win sustained public support. That is where the link between realism and idealism specifically originates. After all, the fact that the possibility even exists for humanitarian intervention is principally due to the blunt fact of American military power. That power—the hundreds of billions of dollars spent for aircraft carriers, submarines, and fighter jets—has been financed by taxpayers for reasons that go beyond lofty principles: such as protecting sea lines of communication and balancing against adversaries. Such power must first be accumulated for amoral reasons before it can be used for moral reasons. For example, it was U.S. surface warships and submarines in the Mediterranean Sea that launched cruise missiles in the 1999 Kosovo War, even though those platforms were not built and funded with a humanitarian purpose in mind. Indeed, the humanitarian interventions in the 1990s in the Balkans, identified with Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and the diplomat Richard Holbrooke, were inextricable from America’s great power responsibilities that would soon extend NATO to the Black Sea in the wake of victory in the Cold War.

Tension between realism and idealism is natural to a high level of engagement abroad, where crises are nonstop, complex, and contentious. Yet the very fact that such tensions exist is proof of a moral tradition that separates America from authoritarian powers such as China and Russia and their one-dimensional realpolitik.

Foreign policy is the foreign extension of a nation’s domestic condition, and a demoralized domestic condition wrought us President Donald Trump in November, 2016. But Trump’s brand of America First neo-isolationism could never delegitimize the other, far more mainstream internationalism of Shultz, Albright, Holbrooke, and others. This is particularly true in an age of high technology, when we can less and less hide from a shrinking, claustrophobic world marked by great power competition and pandemics. It is in that rendezvous with a wider world that realism and idealism are destined to coexist. Great power rivalry is real. But so is a global media environment that is forever judging our actions.

Remember that the Cold War ended in triumph because the United States won the battle for hearts and minds in Communist Eastern Europe. The declaration of martial law in Poland in 1981 was a defeat for the Soviet Union rather than a victory, because it revealed that after decades of Communist Party rule, the largest of the East Bloc satellites still required the military and security services to keep its population in check. The fall of communism across Central and Eastern Europe followed.

Similarly with Hong Kong, where China’s security crackdown has further alienated Taiwan, even as mainland Chinese experience Orwellian repression. Massive human rights violations are now central to Beijing’s method of rule, as Chinese geography encompasses subject peoples such as the Tibetans and Muslim Uighur Turks. The battle for hearts and minds throughout Greater China has commenced, therefore. Winning that battle requires a foreign policy that blends power politics with a values-driven approach attractive to the Chinese and the rest of the world’s peoples. It is that very combination that will provide a decisive edge over America’s adversaries in the coming years and decades. To wit, rather than overtly inject ideology into our bipolar struggle with the Chinese, we need to imply it in our daily emphasis on human rights around the world.

Realism never dies because it is about limits, constraints, and hard choices. Idealism never dies because ever since the Hebrew prophet Isaiah and the Greek tragedian Euripides it has appealed to the human spirit. In the creative tension between the two tendencies America finds its true reputational calling. That was the secret to winning the Cold War. As for our own era of great power struggles, it is partly a matter of recovering the quiet, unassuming example of George Shultz.

No comments:

Post a Comment