By Ekaterina Zolotova

For well over a year, Turkey has been projecting an image of itself that is out of sync with the reality at home. It invaded northern Syria, again, in October 2019; deployed troops to intervene in Libya’s civil war in January 2020; threw its weight decisively behind Azerbaijan in that country’s brief war with Armenia in fall 2020; and had naval standoffs in the Mediterranean with both France (June 2020) and Greece (multiple times, including in August 2020 and January 2021). But behind the curtain is an economy that was grappling with double-digit inflation and a falling currency even before the coronavirus pandemic started wreaking havoc. The Turkish economy is one of the region’s largest, and a default or severe crisis could spread to other major economies, particularly in Europe. Though the exposure of EU economies is manageable, the risk is one more thing for Brussels and EU capitals to worry about at a time when they cannot afford more adversity.

Turkey’s Value – and Its Debt

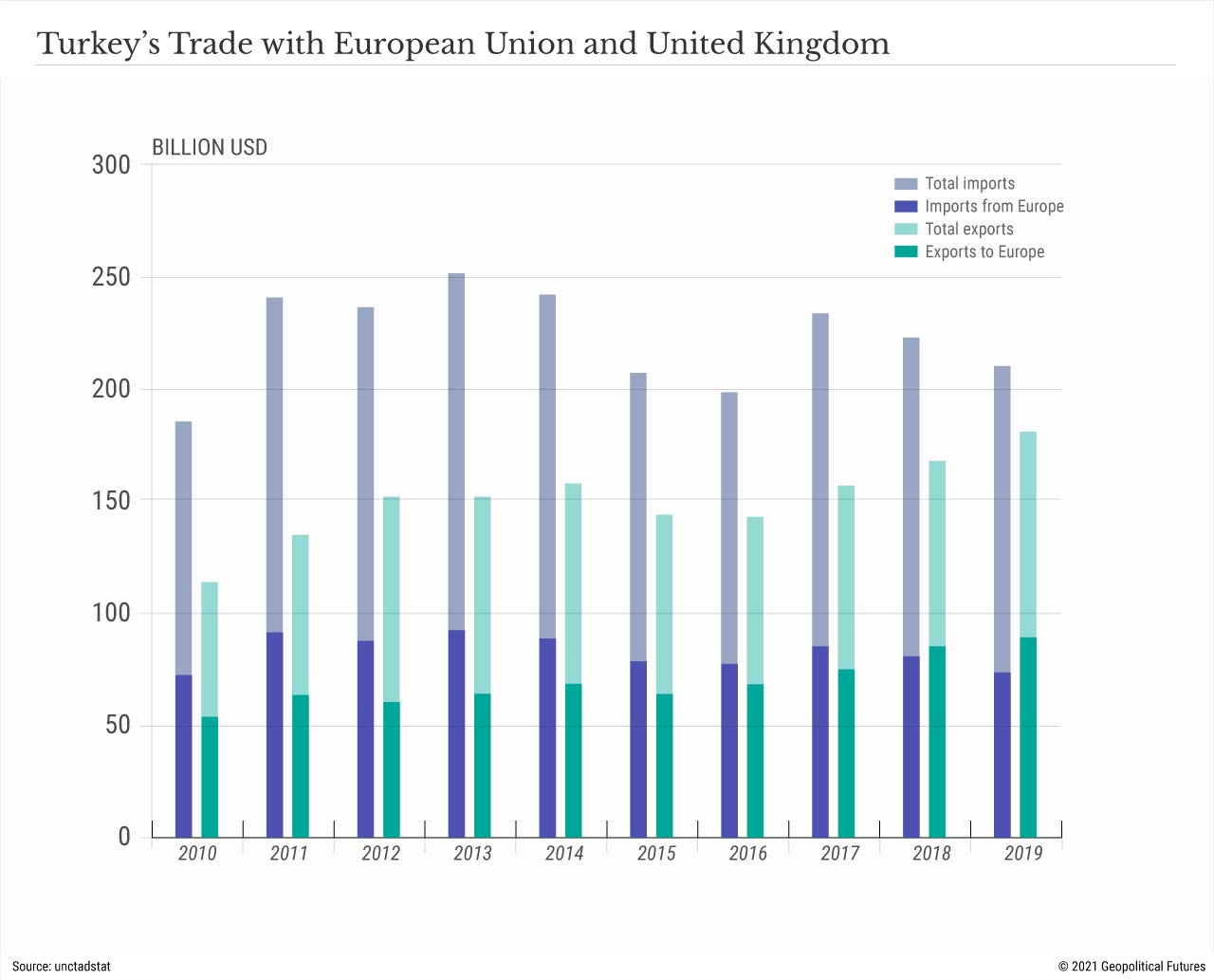

Ankara’s recent aggressive foreign policy has frequently had it butting heads with EU members Greece and Cyprus, but in general Turkey remains an important strategic partner for the European Union in the Middle East. It lies at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, with significant influence over both trade and migration flows. Due to its proximity to Europe and low cost of labor, it is also a major recipient of European investment. In 2019, the EU was Turkey’s top import and export partner – and its leading source of investment – by a wide margin. This is why so many EU member states have been reluctant to take a firm stand against Turkey, despite its expanding presence and even occasional provocations.

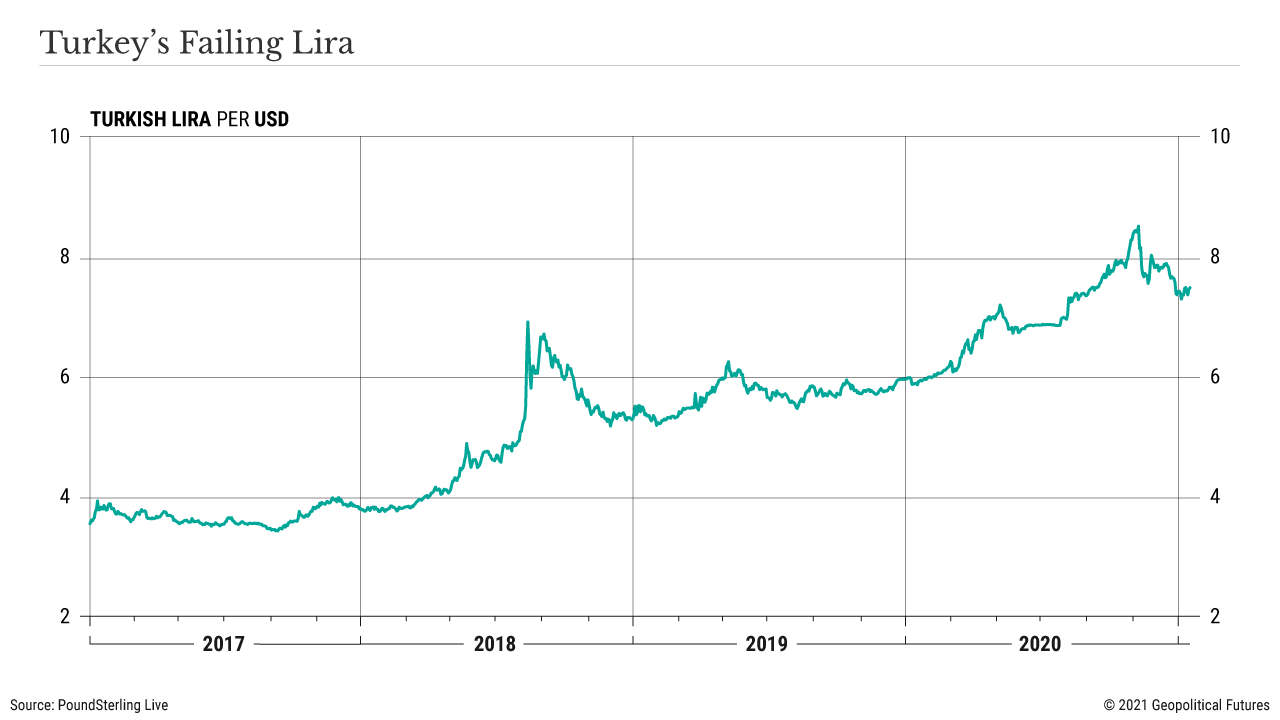

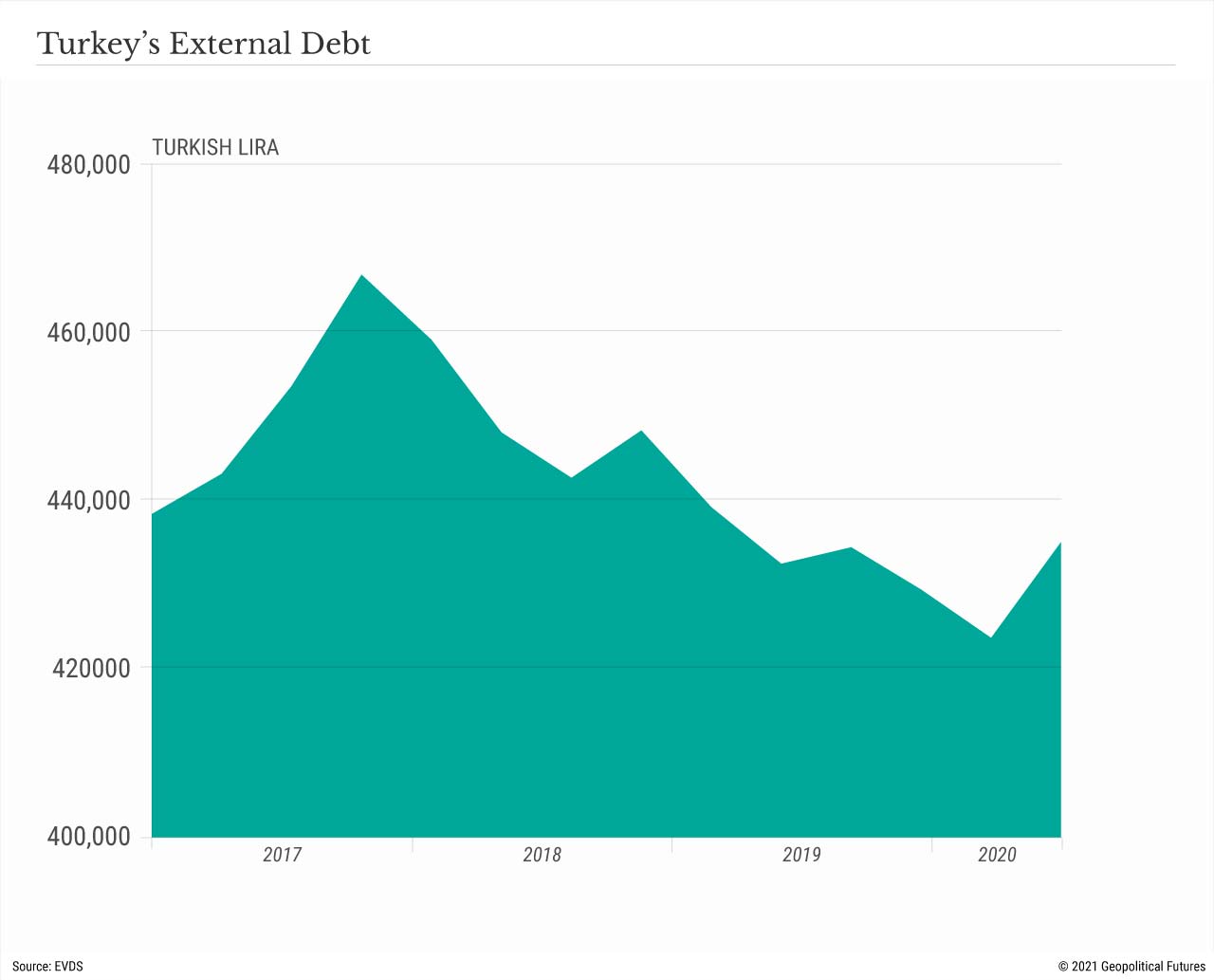

But if Ankara’s actions haven’t gotten Europe’s undivided attention, its debt situation might. Turkey’s public debt is low by most standards – just 41.7 percent of gross domestic product in 2020, or 35.2 percent when central bank assets and other publicly held funds are deducted. The danger, however, is that the Turkish lira will fall so far that Ankara can no longer service its external debt. In 2020, the lira fell by 30 percent against the dollar.

From the perspective of European banks, what’s most concerning is Turkey’s stock of short-term external debt, which rose to $134.6 billion at the end of November. As the lira falls and Turkey exhausts its supply of foreign currency, repayment gets harder. Turkey’s official reserve assets are just $82.7 billion (roughly half in foreign currency reserves and another half in gold). And though the Turkish economy rebounded nicely in the third quarter of 2020, the all-important tourism sector is still struggling.

In the event Turkey can’t pay its debt, it would spell trouble for European banks in several countries. Particularly exposed are Spanish and French banks, which have the most outstanding loans to Turkey of all foreign lenders. European banks reduced their exposure following Turkey’s 2018 currency crisis, but Spanish banks still hold $64 billion of Turkish debt, followed by France ($24 billion), Italy ($21 billion), the U.K. ($13 billion), the U.S. ($9 billion) and Germany ($7 billion).

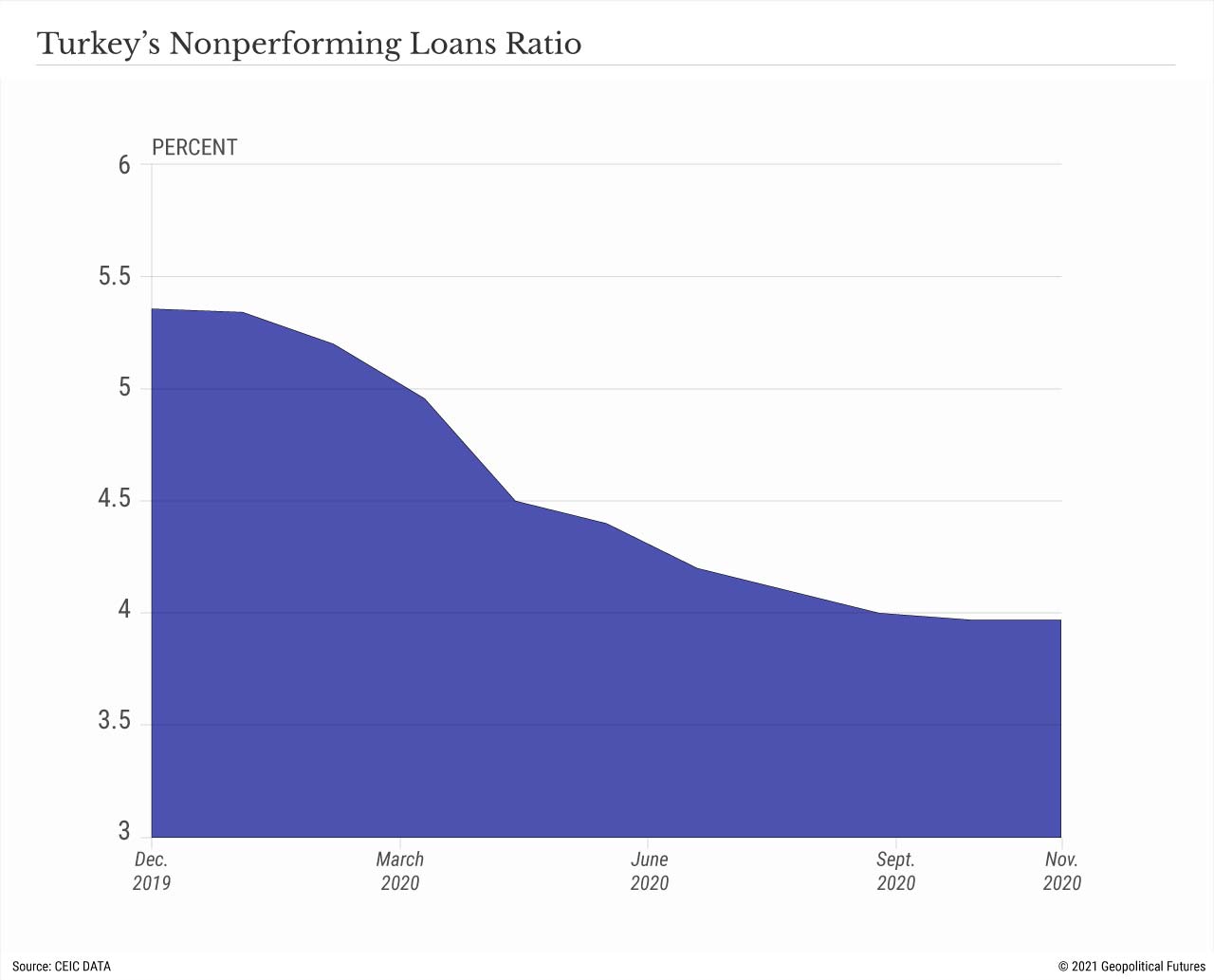

However, these banks can breathe easy because Turkey tends to pay its debts. This year, the Turkish Treasury will repay 449 billion Turkish liras ($53.6 billion) toward its domestic debt and 98.2 billion liras toward its external debt, with interest payments of 121.9 billion liras and 40.3 billion liras, respectively. And it has the resources to pay it. Turkey’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, which has a portfolio of 23 companies from eight different sectors and according to rumors oversees $240 billion in assets, has emerged as the country’s largest source of funding after the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves turned negative. Moreover, Turkey’s ratio of nonperforming loans stood at just 4 percent in November 2020. That could jump to 12 percent by 2021, according to S&P Global Ratings, as bad debts grow alongside credit expansion. This will complicate European banks’ efforts to balance their accounts, but it is hardly the kind of thing that will destroy Europe’s monetary system.

Currency Crisis

Then there is the issue of the Turkish lira itself. Despite recent signs that it has stabilized, it did so only after the central bank increased its benchmark interest rate to a lofty 17 percent, and after Ankara and London signed a free trade deal. Inflation in Turkey has climbed to more than 14 percent, its highest level since August 2019. A rapid devaluation in the price of the lira would hurt European exports to Turkey. Ankara has goosed import demand during the pandemic by lowering interest rates and by increasing access of households and companies to cheap credit, but the Turkish government is unlikely to be able to continue to do so if President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wants to see inflation low, and thus his voters happy.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s foreign trade deficit has widened, increasing the current account deficit and making the need for foreign exchange all the more urgent. Turkey brought in fewer dollars and euros in 2020 thanks to a decline in tourism and exports. That is to say: There is the potential risk that Turkey will not be able to pay for imports from Europe. Its weak economy and even weaker demand for European goods may, in turn, stunt the EU’s economic recovery as it tries to revive its exports. Of course, Europe wants to keep what trade it conducts with Turkey, but Turkey’s share of Europe’s overall trade portfolio is small. In 2019, it was the sixth-largest partner for EU exports (3 percent) and the sixth-largest partner for EU imports (4 percent). This is more of a Turkish problem than an EU problem.

Turkey’s economy, which could go into a technical default, thus halting payments and hurting trade, sounds pretty unpleasant for Europe. But Turkey is constantly looking for new markets that could offset its losses in foreign currency. Primarily it is looking to its east, offering construction services in Azerbaijan, building transport corridors to China, and sending a freight train through the “Iron Silk Road” railway. Turkish authorities intend to increase the export of textile products and steel by 10 percent to the countries of the EU, the Middle East, Asia and North America.

A default therefore looks unlikely, all the other economic problems notwithstanding. In the worst-case scenario, the collapse of the Turkish economy would not mean the collapse of the European economy. And in any case, Ankara has options to stay afloat.

No comments:

Post a Comment