By George Friedman

Last week, U.S. President Joe Biden took two steps in the Middle East. The first was that he notified Congress of his intention to remove the Houthis fighting in Yemen from the government’s list of foreign terrorist organizations. The second was that he said the U.S. would end its support for the Saudi-led campaign in Yemen and would review its relationship with Saudi Arabia over concerns about that country’s human rights record. In and of themselves, these two actions have little meaning. Viewed together, they may represent a radical shift in U.S. Middle East policy. The question, of course, is how and even whether this shift will affect the reality of the region. As I have so often written, policy is the list of things we wish for. Geopolitical reality is what we get.

The Houthis are a major faction in what seems the eternal Yemeni civil war. They are aligned with Iran, facing off against Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The war in Yemen has to a great extent morphed from a civil war into a war between other countries’ proxies. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have been carrying out airstrikes and providing some support on the ground in the fight against the Houthis. Iran, on the other hand, has been providing missiles to the Houthis (or Houthi-appearing Iranian forces), which have been fired into Saudi Arabia.

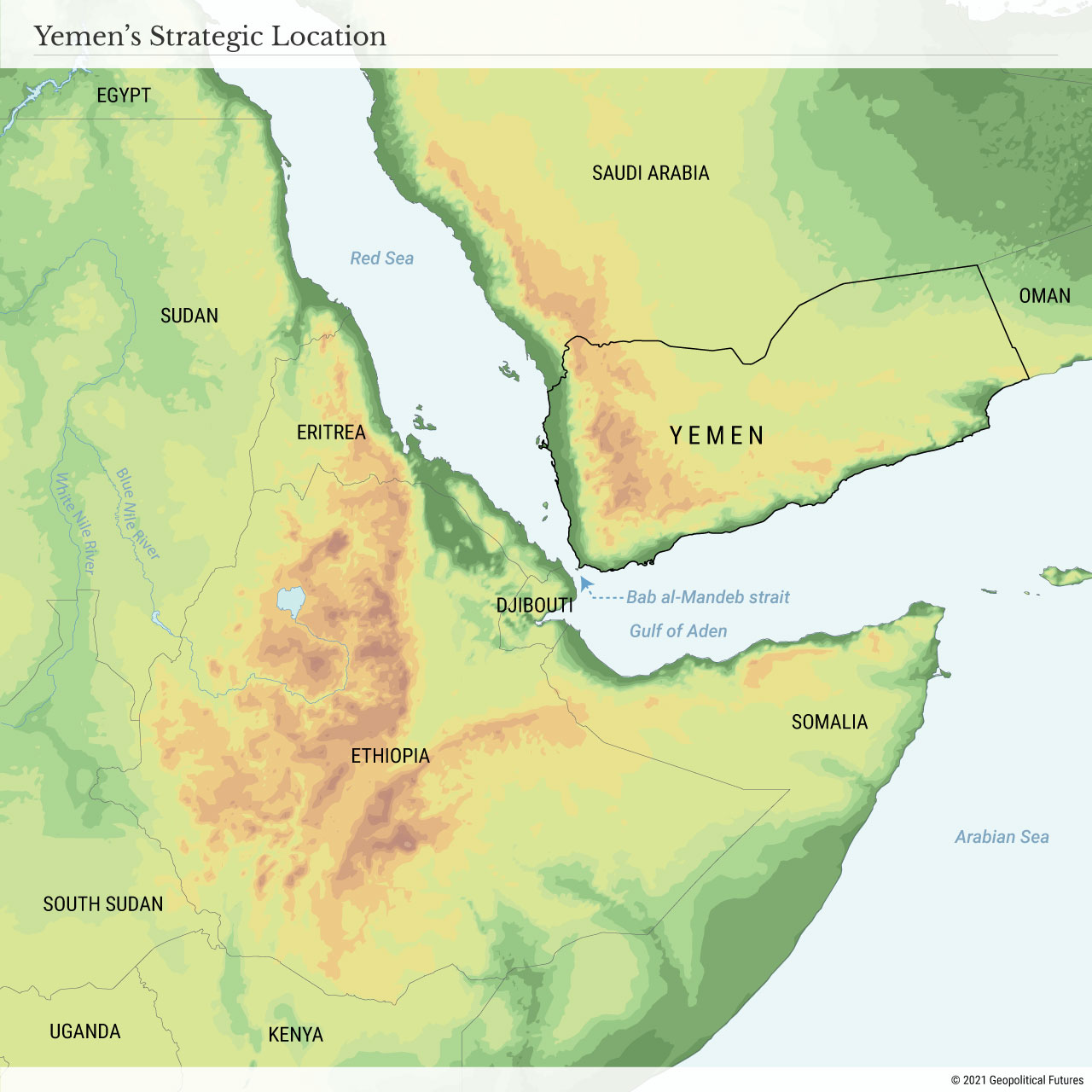

Yemen is a strategic country. It can project force into Saudi Arabia and Oman, or allow more powerful allies to do so. More important, from Yemen’s location a hypothetical, stronger power could close the Bab el Mandeb strait, and in doing so close the Red Sea. Access to the Red Sea is vital: In 1967, Egypt closed the Tiran Straits, blocking Israel from the Red Sea and triggering the Six-Day War.

Yemen is in no position to block the straits itself, but an outside party seeking to sow regional chaos might be. And if it did, it could draw Egypt, Israel and Ethiopia into a conflict they don’t want, and threaten Saudi Arabia and Oman, thereby weakening the Arab position in the Persian Gulf.

Iran is not in Yemen for its health. In the short term (which is maybe the only term there will be), Yemen is a base from which Iran can put pressure on Saudi Arabia, which it sees as its major rival, and also on the UAE, the major native Persian Gulf model, to expend resources on an operation that is not in its immediate national security interest but which it can’t avoid. In the long run, were the Houthis to win the civil war under Iranian patronage, it could both destabilize the region and persuade some Sunni Arab powers to align with Iran, changing the balance of power in the region at the very least.

The agreement between Israel and the UAE, which is rapidly expanding to other powers – including the Saudis, who are full members without signing the accords for domestic reasons – is an anti-Iran coalition. The Sunni Arab states view Iran as their mortal threat, and they see Yemen not only as a test battlefield with Iran but also as a direct assault on core interests, ranging from Syria to Iraq to Yemen itself. The Sunni Arab countries’ fear of Iran is not primarily about nuclear weapons. They see that as one threat among many – as something that Iran doesn’t have and that, if that changes, will be dealt with by Israel. What they fear is Iran’s intrusion in places like Syria and Yemen and the possibility that, in the event of success, these and other countries would turn into Iranian satellites, giving Iran what it really wants, which is the dominant position in the Middle East.

The Trump administration’s position was to treat nuclear weapons in Iran as simply part of a broader threat. In other words, with or without nuclear weapons, Iranian covert operations and subversion could give it a dominant position in the area. Sanctions were designed to cripple Iran internally, while the Abraham Accords were an attempt to create a powerful coalition, not dependent on U.S. direct intervention, to block Iranian adventures.

The decisions to remove the Houthis from the terrorist list and to review the Saudis’ human rights record are not in themselves significant. But the Biden administration appears to be either gesturing toward a new policy or planning one. It has promised to revive the nuclear treaty with Iran. But that was signed in a different Middle East. In today’s Middle East, the solution to the Iranian problem has become indigenous: a massive alliance from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf, including a significant nuclear power, Israel, and other powers prepared to challenge Iran, nuclear or not.

The administration is signaling a move toward a hostile relationship with the Saudis over Yemen and human rights. If it follows through on the former, it will also be moving against the UAE, where the U.S. has bases. And it will be moving against Israel, which sees the Saudis as a critical foundation of the alliance. Saudi Arabia is less stable than it once was, and the ability of the regime to live up to the new administration’s conception of human rights is limited. The threat of an Iran-dominated Yemen is real.

It is difficult to imagine that the Biden administration wants to be forced to deal with an Iran-dominated Yemen or an unstable Saudi Arabia. Therefore, it is difficult to imagine that the two recent gestures by the administration are more than just gestures. There is, of course, another possibility, which is that Biden somehow believes he can coax Iran into some benign relationship with the Sunni Arabs. Doing that by returning to the nuclear treaty as it was originally written might open the door to Iranian interest, but it would panic the rest of the region. This is a region where memories go back centuries, and where alliances, like the current anti-Iran one, are based not on affection but on cold calculation.

Iran is in a box, the rest of the region is in an unprecedented alignment, and as many in the administration learned in Libya, things can get much worse. From where I sit, the most important thing the U.S. learned is to avoid large-scale military involvement in the Middle East. Let Israel, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the rest handle it, because they have no choice. It is their imperative and constraint. The key is to not rock the boat. The danger is that all new administrations want to make their mark. The good thing about this administration is that it remembers Libya, and its commitment to human rights there. The policy might seem virtuous, but the outcome may be far from the intention.

These two gestures are not actions, and it is hard to see where they can lead.

No comments:

Post a Comment