Part of U.S. Military Forces in FY 2021. Beyond the traditional military services, military forces include the new Space Force as well as Special Operations Forces (SOF, which functions as a quasi-service), Department of Defense (DOD) civilians (which perform many functions that military personnel perform in other countries), and contractors (which form a permanent element of the national security establishment, not only in the United States proper but also on overseas battlefields).

Major elements such as a headquarters, appropriations accounts, and capstone doctrine have been established.

Major elements of structure are in place, but decisions are still pending about transfer of most personnel.

Its small size will require heavy reliance on other services, particularly the Air Force, for support functions and a different approach to personnel management.

Special Operations Forces (SOF)

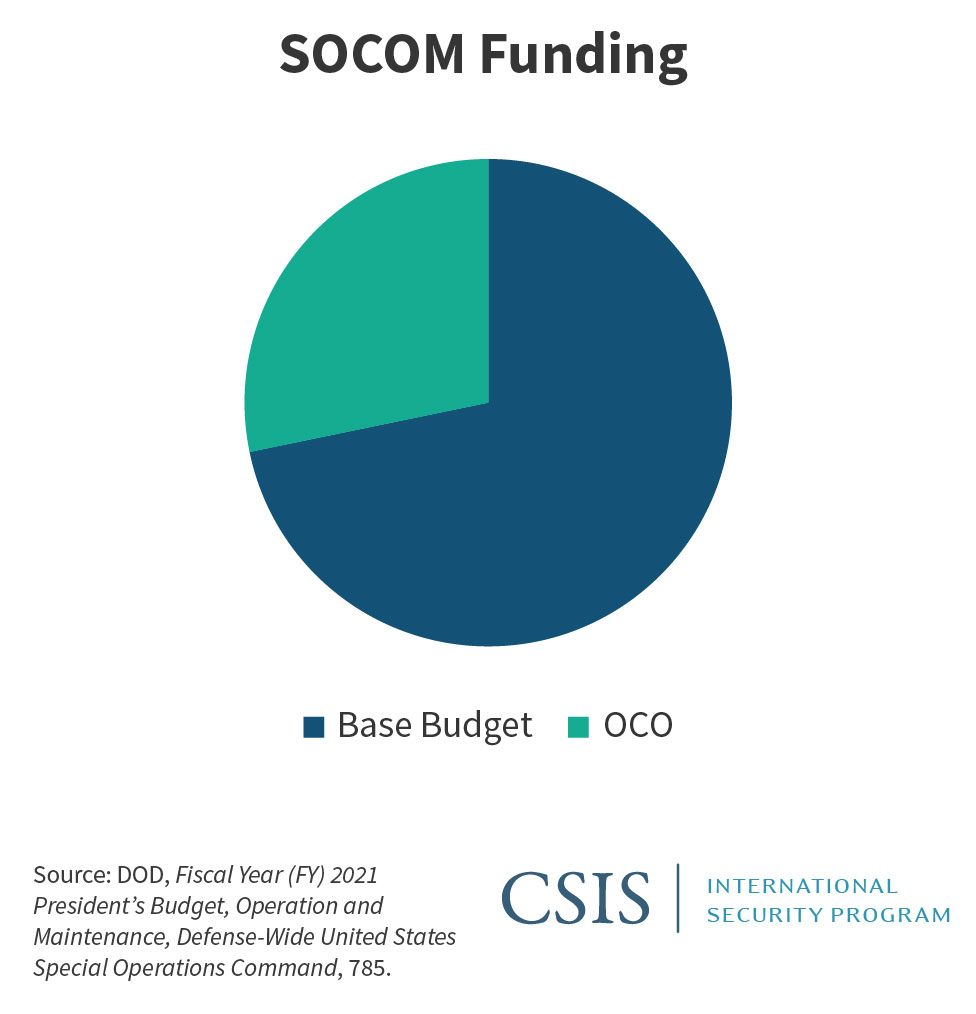

SOF continues its gradual expansion and heavy dependence on Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding.

A broad set of actions to counter recent instances of ethical misconduct by its personnel seems to be having an effect.

DOD Civilians

Despite administration skepticism about the federal bureaucracy, the number of DOD civilians stays at about the same level in FY 2021, retaining the growth of recent years.

This strength reflects the civilian workforce’s contribution to readiness and lethality.

Former secretary of defense Mark Esper’s review of the “fourth estate” cut defense-wide civilians by about 7,000, but increases in the Military Departments offset this decrease.

Contractors

Contractors have become a permanent part of the federal workforce but remain controversial due to enduring questions about cost and what contractors should or should not do.

Operational contractors continue to play a vital role in CENTCOM, holding a 2.8 to 1 ratio of contractors to military (up from 1.7 to 1 last year) as military forces exit Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan while contractors stay behind.

Space Force

The Space Force, officially created on December 20, 2019, is taking shape. The split from the Air Force has been amicable so far, with about a third of the expected personnel having transferred to the new service. Next year will see the final organizational decisions and whether a Biden administration is fully on board with the new service. How the new service will operate long term remains an open question. It will need to create a new organizational culture, and its small size means that it will operate very differently from the other military services.

At the beginning of FY 2021, Space Force personnel are caught between their old identities in the Air Force and their new identities in the Space Force. Although the positions have been transferred, funding is still in Air Force military personnel accounts. This will likely change in FY 2022. Other appropriations―operations and maintenance; research, development, testing and evaluation (RDT&E); and procurement―will transfer in FY 2021.

BUILDING A NEW MILITARY SERVICE

The U.S. Space Force is a separate branch of the armed forces within the Department of the Air Force (motto “Semper supra,” or “Always above”). It will be “organized, trained, and equipped to provide: freedom of operation in, from, into the space domain; and prompt and sustain space operations.”1

Space Force will “remain mission focused by leveraging infrastructure of the U.S. Air Force except in performing those functions that are unique to space or central to the independence of the new armed force.”2 DOD’s Comprehensive Plan for the Organizational Structure of the U.S. Space Force creates a group of career specialties referred to as the “space force core organic” to define those personnel who will be part of the Space Force.3

This guidance also means that the Space Force will rely on a lot of Air Force organizations, as the Marine Corps does with the Navy. However, because of its small size the Space Force will need to go much further in its reliance, so functions such as recruiting will likely come from Air Force institutions with embedded Space Force personnel. The comprehensive plan notes that Space Force will receive more than 80 percent of its critical support functions from the Air Force. This structure may have the advantage of focusing the Space Force on core activities rather than spreading attention across more bureaucratic activities.

Along with establishing the Space Force, the administration has implemented a wide variety of organizational changes as part of reorganizing and emphasizing the national security space enterprise:

Established U.S. Space Command (SPACECOM). Although a combatant command and not a part of the Space Force, SPACECOM will be the operational expression for U.S. space activities and where many Space Force personnel will serve.

Redesignated Air Force Space Command (AFSPC) as the first element of U.S. Space Force, and military members assigned to AFSPC were assigned to the U.S. Space Force.

Appointed General John Raymond as the chief of space operations, the head of the Space Force, and Chief Master Sergeant Roger A. Towberman as the senior enlisted advisor of the U.S. Space Force.

Created a Space Force service headquarters in the Pentagon. This has four major elements: a Human Capital Office, an Operations Office, a Strategy and Resources Office, and a Technology and Innovation Office.4

Published plans for field commands: a Space Operations Command, a Space Training and Readiness Command, and a Space Systems Command. The systems command has received a lot of attention because many advocates want it to have authorities allowing more rapid acquisition and fielding of systems.

Published a capstone doctrine manual, Spacepower, to give a broader context to military operations in space. (Note that “spacepower” is a single word, denoting a concept more than just power in space.)5

Established a new assistant defense secretary for space policy position, a role that Congress required DOD to create in the FY 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

Established (also per FY 2020 NDAA) assistant secretary for space acquisition and integration (ASAF/SP) within the Air Force who reports directly to the secretary of the Air Force.

The Space Force will not send astronauts into orbit. That is the exclusive purview of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, a civilian agency. When the space age began, the United States intentionally made human spaceflight a civilian rather than a military function.

Neither will the Space Force control the satellites of the U.S. Intelligence Community. These fall under the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). However, the Space Force and the NRO will exchange liaison cells.

STILL A WORK IN PROGRESS

About 2,400 military personnel will transfer to the Space Force during the fall of 2020; however, most space force personnel will still be Air Force personnel working in a Space Force organization. The transfer will come in FY 2021. The Space Force and Air Force are setting up a process by which individuals opt to leave the Air Force and join the Space Force.6

Transfers from other services will begin in FY 2022, although DOD has not yet laid out what that mechanism will be. In its FY 2021 budget, for example, the Army signaled plans to transfer 100 personnel. However, there will likely be some tensions about how to allocate space-qualified personnel since the other services are allowed to retain some space capabilities.

The Comprehensive Plan for the Organizational Structure of the U.S. Space Force notes that a wide variety of organic capabilities are “central to the independence of the new armed force,” including doctrine, resources/matériel, personnel management, wargaming, test and evaluation, operational intelligence, and training. When these are established, many will be co-located with Air Force counterparts to leverage existing organizations. Still, the other military services devote thousands of personnel to these functions, numbers that the Space Force cannot match. Instead, it may use government civilians and contractors to a greater degree than the other services.

Early concepts included the eventual creation of a new military department for space, thus breaking the Space Force out from the Department of the Air Force. So far there has been no movement in that direction, and DOD’s concept does not include it.7

Currently there is no reserve component to the Space Force, but there will certainly be one. A reserve component provides strategic depth for U.S. space operations and a mechanism to retain personnel with space-related skills. The politically powerful National Guard has argued for having a role, although the states have no authorities in space.8 Several existing National Guard and reserve units do, however, perform space functions.

A DIFFERENT PERSONNEL STRUCTURE

Because the Space Force will be much smaller, even at full size, than the other services, its personnel structure will be unique. One effect may be cultural. To deal with a small number of personnel to cover so many tasks and organizations, General Raymond, the chief of space operations, has directed the use of mission command by the Space Force. This means that “subordinate echelons are expected to default to action except where a higher echelon has specifically reserved authority.”9

Another aspect is the rank structure. Currently, the Space Force consists of 43 percent officers (2,742 officers out of a total strength of 6,434). That ratio might change a little as more personnel and other organizations are incorporated, but it is unlikely to change very much. Because so few Space Force officers will have the experience of leading troops, the culture will likely evolve to one of officers as highly skilled technicians rather than as leaders.

For a service that will primarily operate satellites from home bases in the United States, the rank structure is not a problem. The challenge will arise when Space Force’s technically focused officers enter the joint community. To prepare its officers for service in these organizations, Space Force will need to develop leadership opportunities and training.

The ability of the Space Force to produce the requisite number of senior leaders from such a small base will also be a challenge. Advocates expect that the Space Force will have two or three four-star officers: the chief of space operations, the vice chief of space operations, and probably the commander of SPACECOM.10

This challenge will ripple down through the organization as the Space Force needs to have officers at the same level as officers in other services in order to compete effectively in DOD’s bureaucratic processes. A RAND study noted the problem, concluding, “being small could hurt the viability of the space force.”11

WILL THE SPACE FORCE SURVIVE THE TRANSITION OF ADMINISTRATIONS?

Although space advocates had been pushing for a Space Force for many years, its creation had elements of a vanity project by a president who reveled in putting his personal stamp on organizations and events. It is unclear whether this association will taint the Space Force in the Biden administration.

Some progressives have recommended that Space Force be abolished as part of a broader effort to reduce defense spending. There is even a Twitter hashtag: #abolishspaceforce. Progressives particularly object to “militarization” of space and the cost of additional bureaucracy.12

However, neither the Biden campaign nor any of its surrogates have said anything against the Space Force. There has not even been a suggestion to re-study the question. Space Force looks permanent.

MEANWHILE, UP IN SPACE

The Space Force launched three major satellites and the X-37B space plane.

A GPS Block III launched on June 30. GPS provides global positioning information, and Block III is the latest upgrade.

An Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF-6) satellite launched on March 26. AEHF replaces the Milstar constellation to provide highly protected communication for high-priority military assets and national leaders.

A TDO-2 satellite launched on the same booster as AEHF-6. TDO-2 is a small satellite vehicle carrying multiple government payloads that will help provide space domain awareness for the Space Force through optical calibration and laser ranging.

One of the two X-37B Space planes went up again in May for another extended classified mission.

Space Force maintains several major satellite constellations along with the ground stations, satellite relays, and space-launch facilities required to establish and sustain these constellations, including:

Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) -MILSTAR, for secure communications;

Wideband Global SATCOM System (WGS), for global communications;

Global Positioning System (GPS), for global positioning;

Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), for weather;

Space-Based Infrared System, for missile defense; and

Geosynchronous Space Situational Awareness Program (GSSAP), for tracking and characterization of manmade orbiting objects.

LOOKING AHEAD

The Space Force has a massive RDT&E appropriation ($10.3 billion) for such a small service. Much of the effort is focused on maintaining and improving existing satellite constellations. The major development is Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (NexGen OPIR), a missile warning satellite system and follow-on to the Space Based Infrared System. The budget allocates $2.3 billion for the effort.

The largest element in the Space Force RDT&E account (35 percent, or $3.6 billion) is classified.

Several major challenges will shape the Space Force of the future:

The Final Composition of Space Force: DOD owes Congress a plan for what personnel and organizations will be incorporated into Space Force. The plan will include elements from the other services as well as additional elements from the Air Force. The final plan will establish the size of Space Force. The larger it is, the easier it will be to staff support organizations and joint billets. However, the other services will want to hang onto some amount of space capability.

Relations with the NRO: The U.S. Intelligence Community successfully fought to be excluded from Space Force. That means that about half of U.S. military launches and satellites do not fall under Space Force. The two organizations are actively working on the relationship, but there is lots of potential for friction.

The Role of Offensive Operations in Space: Space weapons include space-to-space, ground-to-space, and space-to-ground. There are restrictions on nuclear weapons in space but not much else currently. Fears that space debris could render certain orbits unusable have engendered calls for restrictions on antisatellite weapons, but “continued tests of such systems appear to be normalizing the behavior.”13 There are also long-standing criticisms about the “militarization” of space, even though space has had a military function since the first human activity in that domain. (What critics actually mean is the “weaponization” of space.) Neither concern has yet produced binding agreements. The role of weapons in space may be a different matter.14 Current U.S. space doctrine envisions some offensive use of space.

Reliance on Commercial Satellites versus Custom-Designed Military Satellites: Military satellites offer a variety of protections, both physical and electronic, that commercial satellites cannot offer. However, commercial satellites are much less expensive. Further, when the government uses purchased services, it can adjust capacity as needed, buying more or less as the situation demands.

Special Operations Forces (SOF)

Two themes continue—gradual force growth and dependence on OCO funding. Stress on the force has disappeared as a publicly stated concern, as is true of the rest of the department. Deployment-to-dwell numbers approach department goals. Ethical misconduct—a disturbing theme that arose in recent years—seems to have eased after extensive efforts to educate and discipline the force.

FORCE GROWTH

U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) consists of service component commands from each of the four services—Army (Special Forces, Ranger Regiment, Special Operations Aviation, Delta Force), Navy (SEALs, explosive ordnance disposal), Air Force (special purpose aircraft and control teams), and Marine Corps (one “Raider” regiment). Joint Special Operations Command and seven Theater Special Operations Commands conduct operations. SOCOM develops joint doctrine and has the Joint Special Operations University, while extensive service-specific school and doctrine activities reside within the service components.

Over the years, Congress has taken action to make special operations forces like a separate service. The commander of SOCOM has many more authorities than other combatant commanders, having influence over budgets, acquisition requirements, doctrine, promotions, and personnel assignments. The assistant secretary of defense (SO/LIC) has authorities like those of a service secretary for exercising administrative and policy control over designated forces. As a result, special operations forces have a great deal of independence.

SOCOM grew greatly in size during the wars, from 29,500 military personnel in 1999 to 67,092 today.15 It is now approaching the size of the British Army Regular Forces (78,800 in 2020).16 This large post-2001 increase was in response to DOD steadily increasing the number and type of missions SOCOM is expected to carry out. SOCOM has provided DOD’s core direct action and counterterrorism capabilities, in addition to conducting other SOCOM missions such as foreign internal defense, irregular warfare, and civil affairs. Demand for all these missions has grown, not just in Central Command (CENTCOM) but globally as well. SOCOM became DOD’s Coordinating Authority for Countering Violent Extremist Organizations, Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction, and transregional Military Information Support Operations. In effect, the additional responsibilities make SOCOM a “global COCOM.”

SOCOM continues to grow, though slowly, as it accommodates its expanded mission set.17 The challenge, as the Congressional Research Service observed, will be, “[h]ow much larger US SOCOM can grow before its selection and training standards will need to be modified to create and sustain a larger force.”18 The history of special forces in other countries has often been one of expansion, as the desirable traits of such forces are recognized, followed by the eventual attainment of a size where quality cannot be sustained. Then, a new elite group (“special” special forces) is created to regain the quality that has been lost through expansion. It is worth watching for such a phenomenon in SOCOM, although so far there is no indication of the emergence of such units.

SOCOM is highly dependent on OCO funding. For FY 2021, it has requested $3.7 billion in OCO, 28 percent of its total funding and nearly three times the department’s rate overall (10 percent). This heavy usage occurs due to SOCOM’s extensive wartime operations because SOCOM is allowed to fund global (not just CENTCOM) counterterrorism operations in OCO, unlike the military services, and because many base budget elements such as personnel are funded in the service budgets.19 Ninety percent of SOCOM’s OCO funding is for enduring activities.20 Fortunately for SOCOM, OCO appears to be relatively secure, with no immediate effort to eliminate it without compensating increases to the base budget.

The risk is that a Biden administration might make some changes, as elements of the Democratic Party’s left-wing have proposed ending OCO without a full transfer to the base.21 So far, this has not resounded with the broader Democratic national security community.

Dependence on OCO funding raises the broader question of SOCOM alignment with the new National Defense Strategy (NDS). SOCOM’s current operations focus on terrorism and stability operations and demand all of its attention. There is little bandwidth available to think about or prepare for the kind of great power conflicts that the new strategy prioritizes. In the near term, this gap is not a major problem since there is strong support for SOCOM’s current operations.

However, this misalignment could become a longer-term challenge if day-to-day operations decline. This might happen in the context of “ending forever wars” as the Democratic Party platform promises. Travis Sharp notes that “under the NDS [SOCOM’s counterterrorism operations] should consume fewer resources and SOF’s budget share should shrink accordingly.”22 Although SOCOM’s capabilities are broadly useful, how their application would change from a stability operation/regional conflict to a great power conflict needs considerable thought.

High operational tempo (OPTEMPO) plagued SOCOM in the past, putting stress on personnel and their families, resulting in retention challenges and an increase in suicides. However, stress was not mentioned in the FY 2020 posture statement (the last available) and does not appear in official statements since then. It is unclear whether this reflects a reduction in operational demands, a gradual increase in the number of troops to meet the demand, or a change in policy regarding articulation of force stress.

ACQUISITION INNOVATION: LIGHT-ATTACK AIRCRAFT

In addition to acquiring modified versions of service aircraft (e.g., MH-47Gs and MH-60s) SOCOM has picked up the light-attack aircraft program that the Air Force dropped. Called “armed overwatch,” the program would acquire propeller driven aircraft for attack and reconnaissance. The budget proposes to buy 5 aircraft in FY 2021 and 10 aircraft a year from FY 2022 to FY 2025.

This aircraft would operate in relatively permissive environments where sophisticated jets are not needed. The advantage is that it would be much less expensive to acquire and operate. The budget allocates about $20 million per aircraft, with estimates of operating cost running about $500 per flying hour. By contrast, an F-35 costs about $100 million per aircraft and $30,000 per flight hour.23 Thus, the program addresses the inconsistency of having hundred-million-dollar jet aircraft laden with sophisticated electronics and survivability features to drop bombs on insurgents armed with rifles.

If implemented, this would be a radical change in the way air support is provided. The historical trend has been toward multirole jet aircraft which can operate in both high-end and permissive environments, although at extremely high cost. It would also provide SOCOM with a new kind of capability and some independence from support provided by the Air Force. So far, however, Congress has expressed skepticism, questioning whether this new capability is needed, so the program may not survive.24

ETHICAL CHALLENGES

In the last few years, ethical misconduct emerged as a new and disturbing theme for SOF, raising broader questions about SOF personnel attitudes and marring the reputation of SOF, especially the SEALs. Special operations personnel were involved in a variety of crimes, including murders, and then covered up the crimes.25 The risk with any special force is that personnel come to believe that they are not restricted by the rules that bind other servicemembers.

The incidents engendered a lot of soul-searching in the special operations community.26 General Richard Clark, SOCOM commander, ordered an ethics review. The review concluded that the force did not have a “systemic ethics problem.” However, it found that the emphasis on sustained deployments “impacted our culture in some troublesome ways.” The review recommended a variety of actions to improve leadership, discipline, and accountability.27

There is always some question when an institution investigates itself and finds that there are no fundamental problems. Nevertheless, the lack of recent incidents indicates that new policies may be having an effect.

DOD Civilians

After years of growth, the number of DOD civilians would decrease slightly in FY 2021. The deepest cuts are in DOD-wide activities, reflecting former Secretary Esper’s fourth estate review. The relative strength of DOD civilian numbers occurs because civilians help readiness, most being in maintenance and supply functions, not in headquarters (as is often believed).

The United States is unusual in that it has many civilians working in its military establishment where other countries have military personnel. DOD’s civilians perform a wide variety of support functions in intelligence, equipment maintenance, medical care, family support, base operating services, and force management. The department does this because civilians provide long-term expertise, whereas military personnel rotate frequently. Further, the civilian personnel system, for all of its limitations, is more flexible than the military system in that civilian personnel do not need to meet the strict standards for health, fitness, combat skills, and worldwide assignments that military personnel do.

Civilians are often viewed as “overhead” who staff Washington headquarters. In fact, most civilians (96 percent) are outside Washington. Only about 4 percent (31,000) work in management headquarters, and only 27,000 of these work in Washington. Most (73 percent) are in the Military Departments, not in defense-wide activities.

DOD argues that “[e]ffective and appropriate use of civilians allows the Department to focus its Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines on the tasks and functions that are truly military essential—thereby enhancing the readiness and lethality of our warfighters.”28

The large increase in civilian numbers since 2017 occurred for several reasons:

A long-standing initiative to move functions from higher-cost, and difficult to recruit, military personnel to lower-cost civilian personnel; and

Recent DOD efforts to remedy readiness shortfalls, for example, in maintenance and supply, which require more people.

CIVILIAN PAY RAISE

The second key metric on how civilians are faring, after employment numbers, is the annual pay raise. For many years, parity with military pay raises was the norm, but that practice broke down in 2010. In most years since, government civilians have received a smaller pay raise than military personnel.

For FY 2021, the administration proposed a 1.0 percent civilian pay raise (government-wide), whereas the military would get a 3.0 percent increase. This disparity would continue in the future, as the military is projected to receive pay raises of 2.6 percent in FY 2022 through FY 2025, whereas civilians would receive 2.1 percent.29 Congress has frequently been more supportive of civilians but does not seem inclined to change the administration’s proposal this year.

One piece of good news is that the FY 2021 budget implements the expansion of paid parental leave.

SECRETARY ESPER’S “DEFENSE-WIDE REVIEW”

As secretary of the army, Secretary Esper conducted a process called “night court,” whereby he and other senior leaders, civilian and military, reviewed all of the Army’s programs to identify savings that could then be transferred to higher priority programs.30 Over the last year, he has done a similar review for defense-wide activities, mainly the defense agencies and field activities—otherwise known as the “fourth estate.”31 Since defense-wide activities are staffed mostly by civilians, reductions particularly affect the civilian workforce.

The review, appropriately enough called the Defense-Wide Review (DWR), examined all DOD organizations, programs, functions, and activities outside of the Military Departments to identify savings in FY 2021 and in future years. DOD claimed to have found “over $5.7 billion in FY 2021 savings for reinvestment in lethality and readiness, and an additional $2.1 billion in activities and functions to realign to the Military Departments.”32

For this reason, the number of civilians in defense-wide activities would decline by 7,000 in FY 2021 (though the total number of civilians in DOD stays about the same because of increases in the Military Departments).

END OF THE CHIEF MANAGEMENT OFFICER?

The chief management officer (CMO) has a mission of “delivering optimized enterprise business operations to ensure the success of the national defense strategy.”33 The CMO also deals with all the government-wide reform initiatives, ideas for improved governance generated by outside commissions and task forces, and pet projects flowing out of OMB and the White House.

The CMO set up a department-wide reform council and participated in the DWR, eventually documenting real savings. The CMO seemed to be settling into a role of overseeing the fourth estate.34

Despite this apparent success, there has been one widespread dissatisfaction with the office. The position has often been vacant, reflecting a perceived lack of priority. Further, the task is arguably impossible. There is widespread dissatisfaction with DOD’s management, and many observers want to see substantial savings for management reform. However, there is disagreement about the specifics of changes, with every savings proposal facing intense opposition by advocates.

The Defense Business Board recommended abolishing the position.35 Both the House and Senate draft authorization acts would also eliminate the position. It may be doomed like several of its predecessors, for example, the Business Transformation Office.36

GOVERNMENT-WIDE CHANGE AND REORGANIZATION

In its waning days, the Trump administration has proposed creation of a new class of civilian positions called “Schedule F.” This would cover “employees serving in confidential, policy determining, policymaking, or policy advocating positions that are not normally subject to change as a result of a presidential transition.” In effect, this would make some civil service positions more like political appointments.37

The proposal was widely denounced as an administration effort to ensure loyalty and will likely be repealed by the Biden administration. It undermines the political neutrality of the civil service, which was a major achievement in the late-nineteenth century. Nevertheless, it gets to a frustration that every administration has, though much more pointedly in the Trump administration, that the bureaucracy is unresponsive to its initiatives.

Contractors

Contractors have become a permanent element of the federal workforce. Although service contractor numbers seem to be declining, poor data makes that conclusion uncertain. Operational or battlefield contractors now greatly outnumber military personnel in the CENTCOM region (15,000 to 43,800), and the ratio of contractors to military personnel has increased from 1 to 1 in 2008 to 2.8 to 1 today.

Nevertheless, both service and operational contractors remain controversial because of unresolved questions about cost and the appropriate delineation of functions. Although these concerns have been muted for several years, the issue may again arise in a Biden administration because Democrats are more protective of government employees and more skeptical of the private sector.

SERVICE CONTRACTORS

These contractors provide services to the government and are distinct from contractors who provide products.

Chart 4 seems to indicate that the number of service contractors is declining. Many view that as a positive development, regarding contractors as “the invisible government” that lacks visibility and oversight.38 Unfortunately, DOD’s accounting for service contractors is such a mess that it is hard to be sure what is happening.

Numbers for FY 2019, FY 2020, and FY 2021 come from an FY 2021 budget exhibit. However, the numbers exclude service contractors in military construction, RDT&E, and Classified Activities. Although the reason for excluding classified activities is clear, the reason for excluding military construction and RDT&E is not. Numbers for previous fiscal years are inconsistent with numbers for later fiscal years. Numbers for FY 2012, FY 2014, and FY 2015 come from the Defense Manpower Requirements Reports for those respective years. However, they do not include classified organizations, and reporting stopped with FY 2015. These numbers appear to be inconsistent with the later numbers.

Service contractors are controversial because they raise questions about what the government should do and what the private sector should do. On the one hand, government regulations (OMB Circular A-76) state that only government employees should conduct “inherently governmental” activities. On the other hand, the same document states the government should not compete with its citizens and therefore should buy from the private sector whenever it can.39

Outsourcing had been an element of the Clinton and Bush administrations’ “reinventing government” initiatives, but in 2008 to 2010 the Democratic-dominated Congress effectively shut this effort down, and then the Obama administration blocked conversions permanently. This shutdown occurred partly because of concerns about disruptions to the workforce, partly because of questions about the actual achievement of savings, and partly in response to complaints by unions anxious to protect their members’ jobs. The Obama administration believed that it would save money by bringing activities in-house. However, these savings did not materialize when all of the costs of “insourcing” were considered, and the effort ended. Thus, the balance between contractors and the federal workforce has reached a position of equilibrium—there are restrictions against moving in either direction.

This equilibrium is driven in part by unresolved questions about relative costs between the two sectors. Some argue that government is inherently less expensive because it does not need to make a profit. Others argue that government is generally more expensive because it does not need to compete and to be efficient to remain in business. Where commentators come down depends strongly on their views about government and the private sector, with Republicans generally relying more on the private sector and Democrats more on government.

The analytic problem arises from indirect costs. Private-sector prices must include all these costs if an organization is to remain in business over the long term. In government, these costs are widely distributed, so their identification and allocation are difficult.40 A valid comparison requires developing fully-burdened costs—that is, personnel costs with all benefits and support included. DOD and the broader community have made progress on theoretical constructs about what costs to include, but actual numbers do not exist.

There is broad agreement, however, that DOD and the government as a whole do not have a clear strategy for allocating activities among the different elements of its workforce: active-duty military, reserve military, government civilians, and contractors. Organizations as diverse as the Project on Government Oversight, the Defense Business Board, and CSIS have made this point.41 While there is extensive literature on the active/reserve mix, there is much less on government civilians and contractors, largely because of the lack of an assessment of the full costs of each workforce element.

OPERATIONAL CONTRACTORS

Operational contractor support (OCS) “provides supplies and services to the joint force within a designated operational area.” These are the contractors found on overseas battlefields and who do many things that military personnel did in the past.

OCS now forms a permanent element of U.S. forces overseas, along with active-duty personnel, reservists, and government civilians. These contractors exist worldwide, in all the combatant commands. However, attention focuses on contractors in CENTCOM because they have been the most numerous and about which the most data are available.

Contractor numbers in CENTCOM have tracked consistently with the level of operations since 2008, when reporting began. With operations in Afghanistan and Iraq/Syria at a relatively low level and stronger controls and oversight in place, contracting scandals have virtually ceased, and the use of battlefield contractors has receded into the background as a political issue.

Although the widespread and routine use of operational contractors remains controversial in some quarters—Rachael Maddow, the MSNBC commentator, criticized “[reliance] on a pop-up army . . . of greasy, lawless contractors”—use for logistics and administrative functions has become routine in contemporary operations because of the limited numbers of military personnel.42 As a result, some analysts have suggested expanding the use of contractors as military manpower becomes increasingly stretched.43

DOD may have no choice, since force structure increases are modest, as described earlier, and are focused on combat units. This limited force expansion may be strategically sound but drives a greater need for contractor support. Further, administrations routinely put caps on the number of military personnel that can be in theater, but these caps do not include contractors. Thus, contractors can expand the range of military activities without breaking administration policy.

As Table 5 shows, contractors in CENTCOM outnumber military personnel overall, in Afghanistan and now in Iraq. This is a recent change in Iraq, as last year military personnel outnumbered contractors. Thirty-nine percent of operational contractors are U.S. citizens. The rest are third-country nationals and locals.

Other contractors in Iraq/Syria work for organizations outside the DOD―the Department of State, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and U.S. Intelligence Community―but numbers for these are no longer published.

Total contractor numbers are down from a peak of 255,000 in 2008/2009. The ratio of military to contractors has also changed. Whereas in the past the ratio was close to 1 to 1, the ratio for Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria today has soared to 1 military to 3.7 contractors (1 to 2.8 for CENTCOM overall).44 This is up from 1 to 1.7 last year.

This higher proportion of contractors reflects three changes.

First, the large recent decrease in the number of deployed military personnel. Contractor numbers typically lag since the contractors stay on to close up bases and ship out equipment.

Second, troop caps. Because the president has restricted the number of military personnel but not the number of contractors, contractors are likely picking up some tasks formerly done by the military.

Third, the nature of the mission. The more stability-related and less combat-focused, the more the ratio tilts toward contractors, who do support and logistics functions.

As Table 6 shows, about half of contractors perform logistics/maintenance functions and most of the rest do base operations and administrative tasks. Only a small number of contractors do combat-related tasks.

Of the 27,388 contractors in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, 4,260 are in security functions, and of these, 1,813 are in Personnel Security Detachments (PSDs), all in Afghanistan. This latter function is highly sensitive because these contractors carry weapons, interact with the civilian population routinely, and have committed highly publicized abuses in the past. In general, their function is to protect high-value individuals.

DOD requires all contractors to conform with either U.S. or international standards for training, recruiting, and conduct. The industry is participating through its professional organizations—the Professional Services Council, the International Stability Operations Association, and the International Code of Conduct for private security providers Association, among others. The fact that no incidents have arisen recently indicates that the oversight and controls instituted in the last decade have been effective.45

DOD recognizes that operational contractors are a permanent element of its force structure. As a result, DOD has standardized and institutionalized the contracting process that supports not just conflicts but also peacetime needs, such as natural disasters and humanitarian assistance. Some actions DOD has taken are to conduct operational contracting exercises, to incorporate operational contract support into combatant command plans, and to gather lessons-learned systematically.

Mark Cancian (Colonel, USMCR, ret.) is a senior adviser with the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

This report is made possible by general support to CSIS. No direct sponsorship contributed to this report. DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

No comments:

Post a Comment