Touqir Hussain

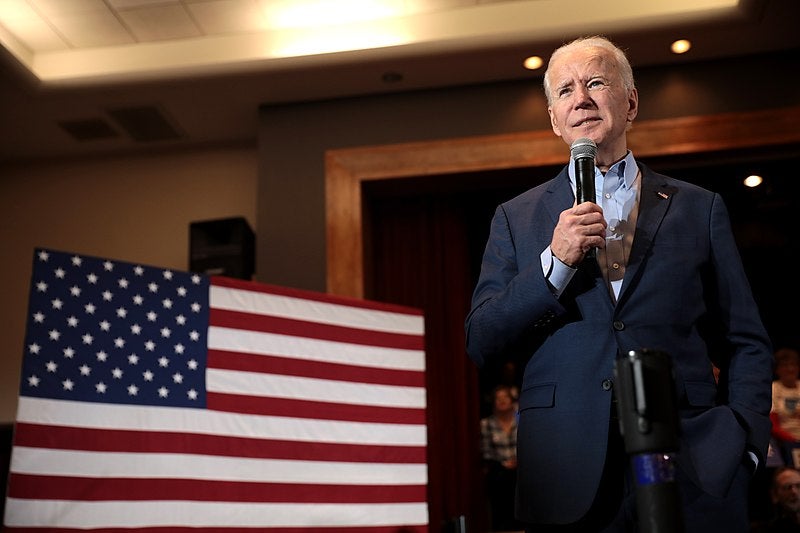

The history of fluctuating United States (US)-Pakistan relations will face another watershed moment under a Joe Biden administration. By now, familiar issues will still weigh on the relationship but present new challenges and opportunities in a changed regional and global environment.

The history of fluctuating United States (US)-Pakistan relations will face another watershed moment under a Joe Biden administration. By now, familiar issues will still weigh on the relationship but present new challenges and opportunities in a changed regional and global environment.What would the United States (US)-Pakistan relationship look like under the likely presidency of Joe Biden? That would depend on his foreign policy. The US has literally been through a national convulsion at the hands of Donald Trump that has affected both its domestic and foreign policies. Much needs to be changed. But the US foreign policy cannot simply be reconstructed in the image of the pre-Trump era which had flaws of its own – the very flaws whose demonisation by Trump contributed to his victory in 2016.

For once, Trump’s disruptive tactics shook some of the long-held internationalist and interventionist assumptions of the American foreign policy establishment –liberal and conservative alike – which has led to endless wars, militarisation of foreign policy and a rise in the influence of globalist elites who gave primacy to personal and corporate interests over America’s interests, especially those of the working class. By accident or design, he ended up undermining public support for some of these “failed” policies. Trump is headed for defeat but some of his ideas will live on.

While, at this stage, Biden’s foreign policy remains largely unknown, and can only be speculated upon, what is well known is the history and nature of the US-Pakistan relationship with which this policy will interact. Over the last more than six decades, these relations have served some of the vital interests of the two countries. But it has not been a normal bilateral relationship, marked as it has been by many paradoxes. It was a transactional relationship dealing with strategic issues on which the two lacked consensus. And typical of a transactional relationship, where you have to make trade-offs and constantly weigh whether you made the right bargain, it caused recurring tensions.

No wonder the relationship has not been without some costs to each. The post-9/11 relationship established a new norm where the limits of this flawed relationship were severely tested as it involved many stakeholders, incited domestic political interests and dealt with an expanded menu of issues: Afghanistan, terrorism, the nuclear question (both the risk of war and of proliferation and the safety of nuclear assets) Jihadism, India-Pakistan relations and, most importantly, China. This added new complexities which the two countries could not cope with, especially as the relationship collided with America’s extraordinary new relationship with India, the failing Afghanistan war and rising US-China tensions.

While many of these issues will continue to weigh on the relationship, a Biden administration may approach them differently. It can neither wind the clock back nor appropriate Trump’s policies. The Democrats have been saying they do not want a “new Cold War”. On 25 October 2020, in the CBS programme, ‘60 Minutes’, Biden said he did not see China as a threat but a competitor. That gives space to US-Pakistan relations.

The fact is Pakistan has its own relevance for the US. And nobody knows it better than Biden, given his long experience in foreign policy in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, where he acquired not only deep knowledge of the region, but also came to know many politicians and leaders personally. Let us not forget he, along with Senator Richard Lugar, was the architect of the Lugar-Biden Bill in 2008 that became the Kerry-Lugar-Berman Bill after he became Vice President. The bill aimed to establish a long-term aid relationship to underwrite a new enhanced partnership with Pakistan.

Biden knows well that there are challenges only Pakistan can help with, principally Afghanistan, where he would like to leave a small counter terrorism force. General Mark Miley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in an interview to the National Public Radio on 11 October 2020, said, “The whole agreement and all of the drawdown plans are conditions-based … The key here is that we’re trying to end a war responsibly, deliberately and to do it on terms that guarantee the safety of the US vital national security interests that are at stake in Afghanistan.” Given the reduction of America’s own military presence, Pakistan’s help for the stabilisation of Afghanistan and safeguarding of US interests may become even more vital than before.

Biden has also taken a keen interest in the safety of Pakistan’s nuclear programme. While Washington will maintain strong ties with India and not allow any action from Jihadists based in Pakistan to destabilise India, it may not let US-India relations shadow US-Pakistan relations as heavily as before. Under Obama and Trump, the so-called de-hyphenation had become reverse hyphenation in favour of India: relations with Pakistan would not influence Washington’s ties with India but US-India relations would limit US-Pakistan ties. This de-hyphenation was, in fact, hyphenation with a new name and may change.

As a medium-sized country with serious security-related challenges and threats, Pakistan would require good relations with all big powers. Pakistan needs the US and vice versa. The hardest thing would be to find a policy towards Pakistan that can overcome contradictions within US-Pakistan relations and between America’s and Pakistan’s other interests. Biden will likely take on this challenge.

Professor Touqir Hussain is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He is a former Ambassador of Pakistan and Diplomatic Adviser to the Prime Minister of Pakistan. He can be contacted at th258@georgetown.edu. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

No comments:

Post a Comment