By Admiral James A. Winnefeld, U.S. Navy (Retired)

It was 1 August 1990. Saddam Hussein had been rattling his sword for six months, threatening to burn Israel and take over Kuwait. But the Soviet Union was falling, consuming the attention of Washington, a town that is really only able to focus on one crisis at a time. The intelligence community was particularly focused on the failing communist empire due to opacity of the Soviet system and the enormous potential consequences of a miscalculation during the transition.

But it suddenly looked like Saddam was serious, and when Iraq began to move forces toward the Kuwaiti border, General Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, held a meeting of the Joint Chiefs and other senior officers at the round table in his office. They were in a tough spot, considering the few options available if the worst occurred.

In January 1990, I transferred from my department head tour at Fighter Squadron-1, based at Naval Air Station Miramar, to the Joint Staff at the Pentagon. Although friends had urged me to stay in the cockpit to enhance my chances of screening for command, the writing on the wall of the Goldwater-Nichols Act’s mandate for joint duty for officers was clear, and I felt the need for some intellectual diversity.

I reported on arrival to the Central Command Branch of the Joint Staff’s small “Joint Operations Directorate,” otherwise known as “JOD.” Three of us—including then-Colonel (and future Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps) William “Spider” Nyland—manned the Central Command Branch. Our cubicles in the bowels of the Pentagon (but within sprinting distance of the elephants, as we used to say) were as close to the operational world as one could get inside the beltway.

Whenever a crisis emerged, all the branches worked together to get through the many tasks that fell to the directorate, including producing briefs and writing warning and deployment orders for military forces. There were a host of other talented officers in JOD, including then-Navy Captain Vern Clark, who led the Pacific Command branch and who would later become the Chief of Naval Operations and a close friend and mentor.

The spring of 1990 was filled with anticipation about the future of the Soviet Union. The Berlin Wall had fallen the previous November, and the Soviet republics were crumbling one by one. However, in the wake of the Iran-Iraq War, Saddam Hussein had begun to flex his muscles. Throughout the beginning of 1990, his repeated threats to reclaim Kuwait as Iraq’s nineteenth province and to “burn” Israel drew little attention in the West.

With the intelligence community consumed by the situation in the Soviet Union/Russia, few took Saddam seriously, except those of us working in JOD. We urged that we be allowed to draw up plans in the event his bluster turned into action, but we were told that Iraq had been friendly during our various confrontations with Iran, and we did not need to plan for operations against a partner nation.

In late July, as Iraqi troops began moving toward the Kuwaiti border, the U.S. ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, sent a confusing signal to Saddam Hussein in her first meeting with him: “We have no opinion on your Arab–Arab conflicts, such as your dispute with Kuwait.” It was a classic example of the need to be crystal clear and firm in communications with other nations; and it has had severe repercussions in the three decades hence. Indeed, in debriefs after Saddam was finally captured, he made it clear that he never would have invaded Kuwait had he any idea at the time that the U.S. was firmly opposed or that the U.S. response would be so robust.

As the crisis matured, I came into work on a weekend to write a deployment order sending aerial tankers and surface-to-air missiles to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The Emirati pilots would fly up near the tankers, but wouldn’t get anywhere close to “plugging in.” It was clear the UAE only wanted U.S. presence on the ground to deter Iraqi action against them, even though they were located all the way at the other end of the Arabian Gulf. They have a come a long way since, including supporting coalition operations in Afghanistan, and the Emirati Air Force has evolved to become one of the best in the world.

With Iraq on the verge of an invasion, I was now one of a small group of officers reporting to the Joint Chiefs, answering tough questions about what options would be available to the President should the worst occur. The paucity of options was daunting. None of the tools we take for granted today—such as Tomahawk missiles, drones, or mass availability of precision guided munitions—were available, either because they did not exist or had not been set up to strike targets in Iraq.

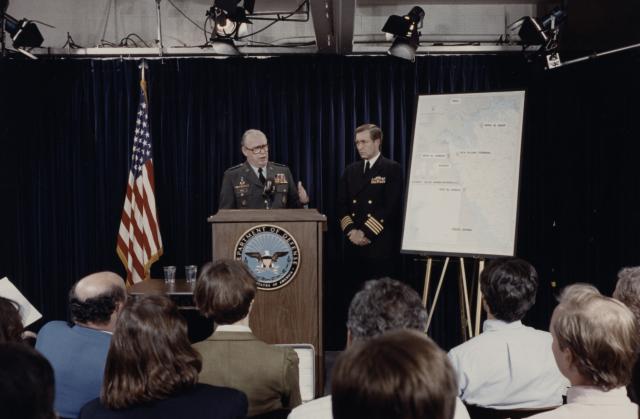

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Colin Powell (left) and Commander, U.S. Central

Command, General Norman Schwarzkopf (right) meet during the lead up to Operation Desert

Storm. (U.S. Naval Institute archives)

The questions came from all angles. General Powell once asked me in his office, with an Air Force general seated at the table with him, how long it would take to convert Air Force B-1 bombers to a conventional role. This is something the B-1 routinely does today, but in those days the aircraft was reserved for a nuclear role. Luckily, I had attended an Air Force brief a few days prior on the service’s initial development of a conventional weapons capability, so I was able to answer General Powell’s question. I responded “Sir, the B-1 bomber is not currently capable of doing that; the Air Force is just now developing the capability.” His irritation with my response was just below the surface, and he politely said, “Son, I’m just a simple infantryman. I didn’t ask you whether they can do it, I asked how long it would take.” I answered, based on the brief I had received, “About two weeks, sir.” Lesson learned: answer a senior leader’s question completely and succinctly.

Meanwhile, Saddam continued to rattle his sword, threatening Kuwait with invasion unless it capitulated to his demands. Sure enough, on the evening of 1 August (the morning of 2 August in Kuwait), I received a phone call at home from the Chief of JOD, then-U.S. Air Force Colonel Ken Hess. “Sandy, put on your uniform and come to work.” I grabbed a pillow and a blanket and told Mary that the Iraqis had probably invaded Kuwait and I wasn’t sure when I’d be home.

It was a busy night. Under the supervision of crusty, irascible, gum-chewing, very Irish Army Lieutenant General Tom Kelly, who served as the Joint Staff Director of Operations, we stood up the Joint Staff Crisis Action Team (CAT), and busily wrote the stack of electronic deployment orders that would start the movement of U.S. forces to the region.

I grew to like General Kelly, despite his gruff manner, even though we did have one run-in. In the middle of the Iraq–Kuwait crisis, another crisis erupted in Liberia, in which a political upheaval required U.S. citizens to be evacuated in what became known as Operation “Sharp Edge.” It was my first opportunity to brief the Joint Chiefs in the fabled “Tank,” where their formal meetings are held and where I spent so much time later in my career. The Joint Staff intelligence chief, Rear Admiral Mike McConnell (who later served as CIA Director) and I were tasked to brief the situation and our evacuation options.

Lieutenant General Tom Kelly, U.S. Army, was the Joint Staff Director of Operations (J-3) during the war. Here, Kelly and Navy Captain David Harrington brief the Pentagon press corps on 25 January 1991. (U.S. Naval Institute archives)

Just before the meeting started, General Powell firmly told the two of us: “We have a lot to talk about in here today; you have no more than five minutes.” Admiral McConnell then proceeded to take four and a half minutes to present the intelligence on the situation in Liberia. As he spoke, and to adhere to General Powell’s guidance, I began whispering to the visual operators behind the screen, eliminating one-by-one what I deemed to be the less important slides of a presentation General Kelly had personally approved. Naval officers are paid to take the initiative and adapt to changing circumstances, right? This was when we used plastic transparencies on overhead projectors, and one by one, the slides started to disappear.

When my turn finally came, I presented the remaining slides, and we dutifully departed the Tank. Later I discovered that a furious General Kelly had chewed out my boss over some lieutenant commander’s “initiative” in shortening “his” brief. Fortunately, I was young enough not to worry too much about my career being torpedoed as a result of my misdeed in the Tank. I felt secure in having obeyed a more senior officer’s explicit order—and my boss did the right thing in not coming down too hard on me. I think I also gained a little credibility among some of the other officers in JOD, who couldn’t believe I’d had the chutzpah to modify a brief Kelly had personally approved.

Kelly was a real character. Many times, a number of other officers and I—mostly colonels and Navy captains—would huddle with him to receive his guidance. Often after we walked out of the room, the colonels and captains couldn’t agree what the general had directed us to do. But none of them wanted to go back into the room to clarify the tasking for fear of a dressing down.

The initial effort to establish defensive positions for Saudi Arabia, known as Operation Desert Shield, and then Operation Desert Storm, was a nine-month endurance race. I worked a 12-hour shift in the CAT, then did my normal job, and tried to get some sleep in the middle. We rotated shifts every few days, so I constantly felt jet lagged. And perhaps worst, I became an early expert in the use of a new thing called PowerPoint as a briefing tool, which became a blessing and a curse.

During the run-up, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney made it clear that he was merely a former congressman from Wyoming and wanted to know more about how the military would fight this war. He requested a brief on a single system from each service that would be relevant to the upcoming conflict. The Army would talk about the M1 tank, the Air Force would describe the F-16, the Navy would walk through counter mine warfare, and the Marine Corps was tasked to discuss amphibious operations.

Many years earlier, my uncle, Carl Builder, wrote a fascinating book, The Masks Of War, which, among other things, describes the differences between the services’ cultures. I was about to witness these differences closely, as I had the task of guiding the services through the process.

The Army’s brief was probably the most professional of all, with a simple PowerPoint presentation that was quickly approved up the chain of command. The major who built the brief worked on it directly for the Army’s chief of staff. A colonel knowledgeable in armored warfare gave the brief, which went well.

The Air Force put together a beautiful marketing presentation under the personal guidance of Chief of Staff General Merrill McPeak. Their highly polished product was to be given by a professional briefer, but Cheney didn’t want a senior officer in the brief. So, much to his frustration, McPeak was not allowed in the room. This was nearly a disaster, for just as quickly as the major slid his PowerPoint folder across the table, Cheney slid it off to the side. The professional briefer was on his own, without slick graphics or deep knowledge of the topic, but somehow made it through the process unscathed.

The Navy handed its task to a “salty” and grumpy senior captain, who reluctantly put together what could only be described as a crayon-and-stick-figure presentation. To my relief, Cheney swept this presentation off to the side as well, preferring to hear directly from the briefer. Fortunately, the captain knew his stuff and gave Cheney a good feel for the ins and outs of mine warfare in the Arabian Gulf.

The Marine Corps’ presentation went the same way. All four presentations matched almost perfectly what my uncle later wrote about service culture.

The war was over more quickly and with less bloodshed than anyone expected, largely because all of the capability the nation had built for a war in Europe—that now seemed irrelevant because of the fall of the Iron Curtain—had been moved to the desert and unleashed on the hapless Iraqi Army. It was a showcase for new technology, and the Army’s lightning fast ability to overwhelm a lesser adversary in conventional maneuver warfare. It was hard to watch Lieutenant General Kelly, an Army tank officer, grow pale when we showed him video of Iraqi tanks being taken out like sitting ducks by precision-guided munitions.

Our success in the war shocked the Russians and the Chinese. The decision by President George H. W. Bush to end the war when our objective of ejecting Iraqi forces from Kuwait and restoring that nation’s sovereignty was accomplished—rather than continuing on to overthrow Saddam Hussein—was one of the wisest in our nation’s history. This decision, influenced and supported by thoughtful leaders like Secretary of State James Baker and Chairman Powell, strongly informed my later views on the use of national power.

This war was also a watershed for joint warfare, in many different ways. One of the most important was the integration of air power. Previously, the Air Force had developed its own industrial-like process for managing air power in large and sustained wars, such as a long conflict in Europe. This included a very robust air operations center concept that managed a cyclical (though somewhat bureaucratic) process for assigning sorties on a daily basis through a vehicle known as the air tasking order (ATO). It was complex poetry in motion. Meanwhile, the U.S. Navy had refined the art of one-off, single-day contingency operations through its near-continuous planning for strikes against Iranian forces in the Gulf had they ever been needed.

One of the lessons of Desert Storm was the integration of joint and combined air power. All air

operations in the Central Command theater today are scheduled and managed at the Combined

Air Operations Center at Al Udeid Air Base in Qatar. (U.S. Air Force Alexander Riedel)

Not only was the Navy relatively ignorant of the Air Force’s ATO process, the tactics it used were completely different. For example, in a one-off strike that does not take long, it is feasible to lob a near-continuous and preemptive hail of antiradiation weapons into the vicinity of a target to suppress enemy air defenses. It is simply impossible to do this in a large, sustained conflict without quickly running out of weapons

So, the Navy and Air Force had unintentionally veered away from each other in this and many other ways. The first Gulf War was a handy catalyst to bring the services back together doctrinally. Similar challenges arose with Marine Corps aviation, and an uneasy truce ensued in which the Marines were essentially allowed to manage their own airpower to augment their supporting fires, albeit within the ATO, while offering any excess sorties to the rest of the joint force. A great debate also occurred over the efficacy of deep strikes to whittle down an enemy’s capability (the Air Force position) versus close air support to enable troops on the ground (the Army’s position). Most of these doctrinal issues have been resolved over the intervening years.

Not long after the war was over, the Bush administration decided to provide humanitarian relief to the Kurds in northern Iraq, who were being brutally suppressed by Saddam Hussein in the wake of the war. Whether they were being starved or gassed, the Kurds were in rough shape and pleading for help. When the decision was taken on short notice to support the Kurds late one Friday afternoon, I was called in by Lieutenant General Martin Brandtner, a Marine who had been awarded two Navy Crosses in Vietnam and who had relieved General Kelly a month or so earlier. Brandtner had just received this guidance and directed me to write an execute order to make it happen.

So, I dashed back to my computer, pulled up another previous order, “saved as”, and began filling in the new details. Needing a name for the operation, and under the somewhat unwieldy naming rules used by the Joint Staff, I came up with the title “Provide Comfort.” I ran back into General Brandtner’s office and put the completed order on the desk in front of him. He smiled, looked up, and said “You know this name is pretty good, and it’s going to make history.” Out went the deployment order, and the name stuck. Many subsequent relief operations used the name “Provide” followed by another word. I was sure I had just used five of my proverbial fifteen minutes of fame, albeit anonymously.

While not as exciting as serving in combat during Desert Shield, I was blessed to have had a front row seat to the policy formulation and decision-making process that guided the war, which was incredibly useful later in my career.

No comments:

Post a Comment