By Jaroslav Krasny

In the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, the Trump Administration announced its intention to expand the US nuclear arsenal under the doctrine of so-called “flexible deterrence,” including a tactical nuclear weapons upgrade. The administration claimed that even if these nuclear weapons were detonated on the high seas or in airbursts, they would still be in compliance with the principles of the law of armed conflict—as long as they were deployed against military objectives.

But their arguments disregard the physical consequences of such weapons use on combatants. Even the limited use of a low-yield nuclear device would violate the customary principles of the law of armed conflict and be contrary to the principle of the “prohibition of weapons of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.” This can be seen by examining the medical data regarding Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors. By analyzing long-term health effects, we can see that even tactical, low-yield, nuclear weapons would demonstrably inflict unnecessary injury, breaching a fundamental principle of the law of war.

But first, some background.

Some context. The international community has already expressed grave concern that the recent deployment of a low-yield warhead on submarine-launched ballistic missiles has radically lowered the nuclear threshold. With this in mind, the question that follows is: “Could the tactical use of low-yield nuclear weapons be lawful on today’s battlefield?”

No specific treaty currently in force effectively prohibits their use. Therefore, the rules that would apply to the use of nuclear weapons come largely from two sources: the Geneva Conventions of 1949, and the long-established customary principles of jus in bello—the law of armed conflict applicable to conventional weapons. Formally codified during the late 19th century, the law of armed conflict reaffirmed that the only legitimate objective of belligerents is to weaken the opponent’s armed forces. The means to achieve this objective are also limited.

These codified principles represent generally accepted practices among States, and compliance with them denotes a legal obligation, as it is a form of what is known as “international customary law”—meaning that it is binding upon all States without exception, unlike conventional or treaty law. Customary international law concerning the targeting and legality of weapons includes the most fundamental principles that states seldom challenge, including the concepts of military necessity, proportionality, distinction, and humanity. Consequently, due to their customary status, the customary law would apply to any use of nuclear weapons as well.

The so-called “tailored response” that is called for in the US Nuclear Posture Review of 2018 would be achieved by a weapons upgrade and the deployment of low-yield tactical nuclear weapons; both of these approaches are perceived by the United States and the Russian Federation as vital instruments towards an effective strategy of flexible deterrence. However, selecting lower yields or choosing a specific method of deployment—that is, against scarcely populated areas or remote military installations—does not ultimately put limited nuclear war in compliance with the law of war.

The concept of a limited nuclear war is nothing new; the idea itself dates back to President Eisenhower. In addition, the idea of flexible deterrence was advocated by former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in the 1960s, who elaborated upon the idea by arguing for theories such as controlled or deliberate response, gradual deterrence, measured retaliation, second-strike counterforce, damage limitation, city avoidance, escalation management, and escalation dominance. Under these hypothetical scenarios, a so-called “limited” nuclear war sets restrictions on the numbers or types of nuclear weapons, the scope of the battlefield, the military objectives, the selection of targets, and the duration of the war—that is, the time between the first and the last use of the nuclear weapons. Whether escalation can, in reality, remain controlled or “managed” is an issue outside the scope of the law of armed conflict.

States that already possess nuclear weapons have opined in their statements before the International Court of Justice that customary law would not necessarily render the use of nuclear weapons innately illegal. For instance, the United States argued that the legality of the use of nuclear weapons would depend on the specific circumstances of their deployment. In its Advisory Opinion, the court stated that customary and conventional law neither allows nor prohibits the use of nuclear weapons.

The court then contradicted itself by stating that while it would generally be contrary to the principles of international humanitarian law to use nuclear weapons, the Court was unable to decide whether such use would be unlawful under what it termed “extreme circumstances where survival of a state is at stake.”

The International Court of Justice did not offer any more clarity but did reaffirm that the general principles of the law of armed conflict would apply to the use of nuclear weapons.

It is important to note that these discussions mostly revolved around the use of relatively low-yield weapons according to McNamara’s vision of a controlled, managed, limited nuclear war involving the deployment of a relatively small number of low-yield weapons that would presumably result in limited collateral damage and destruction. It would undoubtedly be challenging to argue for the legality of the use of high-yield nuclear weapons on the modern, mostly urban, battlefield—or to argue for a massive nuclear exchange, which would result in vast destruction and tremendous loss of life.

Low-yield nuclear weapons. There is no consensus on what constitutes a low-yield nuclear weapon, although the US Doctrine for Joint Theater Nuclear Operations of 1996 recognizes five categories of nuclear yield: very low (less than 1 kiloton), low (1-to-10 kilotons), medium (over 10-to-50 kilotons), high (over 50-to-500 kilotons) and very high (over 500 kilotons).

Given the yields of current nuclear arsenals, however, it makes sense for the purpose of legal analysis to consider the yield of Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs—16 and 20 kilotons, respectively—to be low-yield. It is crucial to keep in mind that some of the currently deployed nuclear weapons can have a significantly lower yield than that of Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

The perfect example would be the W76-2 warhead, currently deployed on the USS Tennessee with a yield of 5-to-7 kilotons. As stated above, even though one could argue that no specific treaty effectively prohibits their use, currently applicable customary principles of the law of armed conflict do indeed apply to any combat deployment of nuclear weapons. Consequently, the questions are: Which particular principles would apply? And do they render the use of even low-yield (nuclear weapons of less than 20 kilotons) illegal under all conceivable circumstances? (To complicate matters, the B61-Mod 12 gravity bomb has a yield of up to 50 kilotons but it includes the option to select lower yields.)

Customary principles and the use of nuclear weapons. States are the primary source of customary rules. Therefore, while not a source of law in themselves, military manuals can help identify norms that states perceive as customary. For example, the United Kingdom Manual of the Law of Armed Conflict identifies four fundamental customary principles: military necessity, distinction, proportionality, and humanity. Meanwhile, in the United States, the Defense Department places “honor” as a fundamental principle in place of humanity. Nevertheless, these two principles are, to a certain extent, similar.

What it comes down to, at the end of the day, is what is humane. But what weapon or means of warfare is “humane”? Could the use of incendiary weapons, such as napalm, thermobaric bombs, or even flamethrowers, be humane? The law of armed conflict is pragmatic, and states recognize it as such. Consequently, it might seem credible for states to argue for the legality of the use of nuclear weapons. However, the principle of humanity that appears in the preamble of the Hague Conventions (the Martens Clause) is also a fundamental principle of customary law. Rooted in the principle of humanity is the prohibition of superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering—that is, inflicting injury or suffering without any military value. This fundamental principle, when breached, could amount to a war crime.

The unnecessary suffering principle was behind the prohibition of chemical and biological weapons, antipersonnel landmines, blinding lasers, and other weapons and weapon systems.

Superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering, as applied to nuclear weapons. The use of warfare that is of a nature to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering is prohibited under customary law and Article 35(2) of the Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions of 1949. Violation of this principle could constitute a war crime. Superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering is not an absolute rule but a comparative one, where exposure to ionizing radiation does not give the attacker or defender any military advantage but does unnecessarily aggravate the suffering of affected personnel.

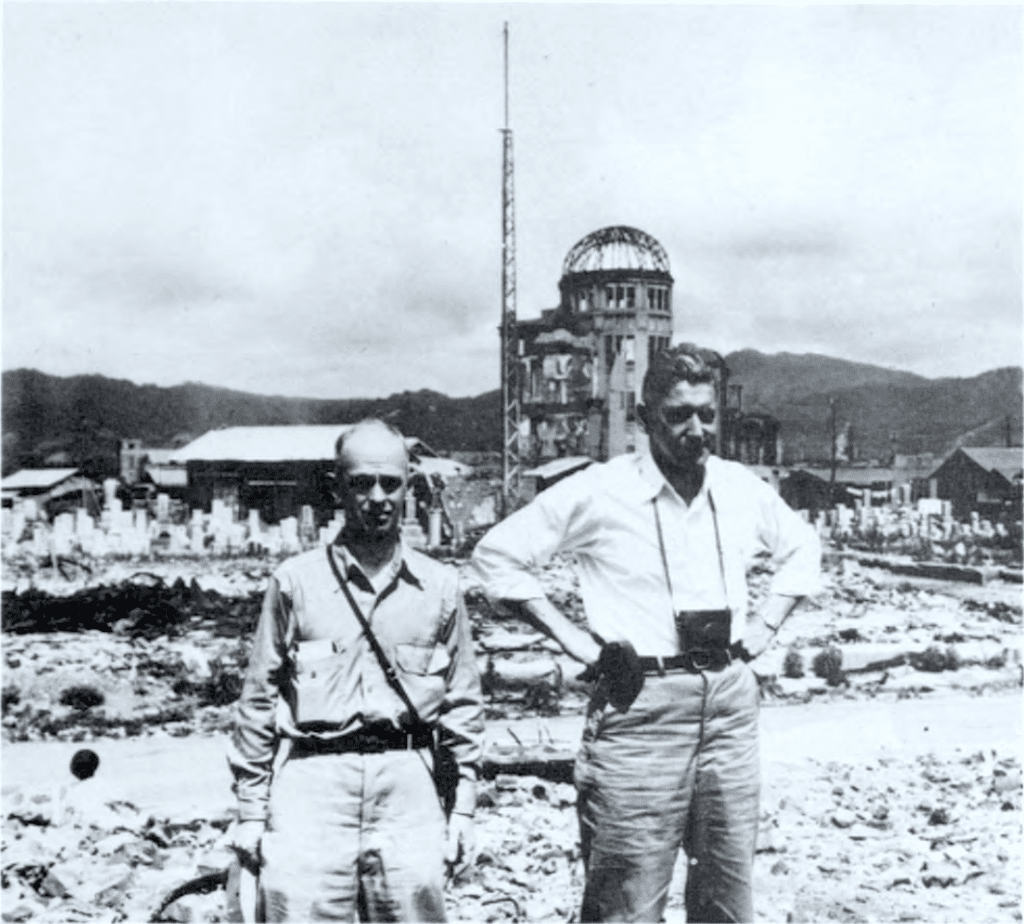

With this in mind, let us look at what happens in the typical nuclear blast. Radiation accounts for roughly 17 percent of the overall energy distribution during the nuclear explosion. Flash burns, blast, and radiation injuries interact in a complex fashion affecting the human body simultaneously. Ionizing radiation substantially complicates the healing process of thermal injuries by lowering resistance to infections. Studies on the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings confirmed that the first two weeks are critical. Within a radius of one-to-two kilometers, victims usually died in 7-to-10 days with cerebral symptoms, including convulsions and delirium. After two weeks, the second stage of acute radiation illness followed, with a fatality rate of about one-tenth of those exposed. By the end of the fourth month, the victims generally showed improvement. However, the symptoms kept reappearing and generated further anxiety and fear among survivors, and the overall improvement beyond four months was in no way an indicator of the overall mortality rate due to the exposure to nuclear explosion. The late effects continued years after a single high dose exposure. The main argument for the unnecessary suffering, therefore, lies in the long-term health effects of ionizing radiation.

According to the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, long-term health effects include blood disorders (such as various forms of leukemia), solid cancers, ocular lesions, and cataracts. Radiation may also cause developmental disorders for those exposed in utero, including those that affect mental performance and microcephaly. Those exposed to the bomb are 79 percent more like to develop leukemia, especially in the first 5-to-10 years after exposure; after the risk for leukemia peaks in 10 years, they are also 47 percent more likely to get solid cancers. Thyroid cancer manifested earlier than other malignancies, which include lung, stomach, breast, colorectal, and liver tumors. The brain and central nervous system were also affected by a significant risk of tumors, particularly schwannoma—a type of cancer also detected in the so-called atomic veterans exposed during weapons testing.

Long-term health effects will be haunting the survivors or hibakusha for the rest of their lives. Following the bombing, many who miraculously survived the horrible ordeal of the nuclear inferno and seemingly were on the path to recovery suddenly developed purple spots (purpura) and started bleeding from their gums, a condition accompanied by debilitating loss of energy, their health slowly deteriorating until an excruciating death. Even those who survived for decades lived the constant fear of what would come next week or next month. Many said that they felt their lives ended on the day of the bombing.

Such an ordeal would not be much different for any combatant suffering under effects of one of today’s “low-yield” nuclear bombs. The threat of invisible disease with a possible death sentence would loom for years to come. Once the sentence is given, an effective remedy is almost non-existent.

The proponents of nuclear weapons can base their arguments for the legality of the use of nuclear weapons on countering arguments about the principles of distinction, necessity, or proportionality. But they can hardly reconcile the use with the prohibition of unnecessary suffering. Ionizing radiation does not serve any purpose under military necessity. It would uselessly aggravate the suffering of combatants while rendering the death of some of the affected inevitable. The trend of limiting the effects of hostilities by developing precise means of warfare needs to take precedence. States currently possess more suitable and legal means of warfare for today’s battlefield in their arsenals. Nuclear weapons of any yield cause injuries that are incompatible with the principles and overall objectives of the law of armed conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment