BY SCOTT REEVES

The coronavirus pandemic has roiled the markets, tossed most fiscal assumptions to the wind and driven the national debt to the highest level since World War II, as the government spent heavily to support the economy.

The U.S. Treasury Department's final report for fiscal year 2020 showed a record $3.1 trillion deficit for the year, with debt held by bondholders totaling $21 trillion.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that federal debt this year will total 102% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—the value of all goods and services produced in a year. But the CBO's estimate may be optimistic. Preliminary figures peg this year's federal debt at about 136% of GDP.

Even with spending cuts or higher taxes, debt is projected to rise as a share of the nation's economy, increasing to 109% of GDP by 2030 and 195% by 2050. That means that after the emergency spending and borrowing during the COVID-19 pandemic ends, the federal debt will likely continue to grow, and may be nearly twice as large as the nation's economy due to existing laws, programs and promises.

Few would argue that additional spending was not necessary to support the economy and help workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic. The Federal Reserve, the nation's central bank, slashed interest rates to nearly zero to stimulate consumer spending, which represents about two-thirds of the U.S. economy.

As the Biden administration prepares new spending plans for vaccine distribution, infrastructure repairs, public transportation, schools, healthcare and green energy, the national debt is emerging once again as a political issue in 2021.

In this century, that argument was advanced by Republican President George W. Bush's vice president, Dick Cheney, a prominent conservative. When questioned about deficit spending, Cheney famously said, "Reagan proved deficits don't matter."

The "debt doesn't matter" argument assumes that bondholders will be willing to buy U.S. debt at low rates indefinitely—even if yields are consistently below the rate of inflation and more lucrative investments are available.

Interest rates are likely to remain low for several years. But borrowing isn't free, and a one percentage point increase in interest rates would cost about another $200 billion a year, about three times the annual budget of U.S. Department of Education.

Arguing that debt doesn't matter also assumes that the economy will continue to grow. At 1% interest, the debt grows by about that amount annually. But if GDP increases at 2%, the debt to-GDP-ratio declines each year and within a few decades returns to prior levels.

But changes that happen over decades are rarely a consideration in U.S. politics.

"Politicians have a short-term mentality and want to get re-elected every two, four or six years," Chris Rasmussen, associate professor of history at Fairleigh Dickinson University told Newsweek. "There isn't much political will to do anything about the debt. Democrats don't want to give up social spending and Republicans don't want to raise taxes or cut the defense budget."

Three States Hold Primary Elections During Pandemic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) is selling $58 sweatshirts on her campaign website. She's shown above campaigning on June 23, 2020 in the Bronx borough of New York City. Ocasio-Cortez is running for re-election in the 14th congressional district against Michelle Caruso-Cabrera, a former CNBC anchor.PHOTO BY STEPHANIE KEITH/GETTY IMAGES/GETTY

Three States Hold Primary Elections During Pandemic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) is selling $58 sweatshirts on her campaign website. She's shown above campaigning on June 23, 2020 in the Bronx borough of New York City. Ocasio-Cortez is running for re-election in the 14th congressional district against Michelle Caruso-Cabrera, a former CNBC anchor.PHOTO BY STEPHANIE KEITH/GETTY IMAGES/GETTYRasmussen said many Americans don't understand the national debt. But some are taking note—particularly the young.

"Students are vaguely aware of the national debt," Rasmussen said. "They have a sense the Baby Boom generation is going to stick them with the bills."

But unless it affects them directly and personally, most people don't give it much thought, he said.

"People see the numbers and because the sky isn't falling, most think, 'I guess we're OK,'" Rasmussen said.

In the nation's history recessions, wars and domestic spending have all contributed to increases in the national debt. The debt-to-GDP ratio is the number analysts track to determine if the U.S. can cover its debt. Economists often note that the U.S. can't default on its debt without causing a global economic crisis.

Argentina defaulted on about $80 billion in debt in 2001. The action sparked years of litigation, but other than bondholders, the world hardly noticed because Argentina's economy is small as compared with those of the U.S., the European Union, Japan, India and China.

Buenos Aires, Argentina—President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner waves from a balcony inside the presidential palace. Argentina has defaulted on its debt following the 2012 ruling of U.S. District Judge Thomas Griesa, who said the country could not keep paying its bondholders while not also paying what are known as the “holdouts”—hedge funds that want to be paid an estimated $1.5 billion.MARCOS BRINDICCI/REUTERS

Buenos Aires, Argentina—President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner waves from a balcony inside the presidential palace. Argentina has defaulted on its debt following the 2012 ruling of U.S. District Judge Thomas Griesa, who said the country could not keep paying its bondholders while not also paying what are known as the “holdouts”—hedge funds that want to be paid an estimated $1.5 billion.MARCOS BRINDICCI/REUTERSHowever, in May Argentina defaulted on its sovereign debt for the ninth time since gaining independence from Spain in1816 after failing to reach a deal on a $500 million interest payment amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Analysts fear Argentina's default could be just the first in a falling line of dominos toppled by the pandemic. Lebanon defaulted on its debt in March, and Fitch Ratings anticipates more will follow. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have asked lenders to suspend payments for some of the world's poorest nations.

Few suggest the U.S. is the next Argentina, but a sharp increase in the national debt raises a basic question: What's ahead?

The downbeat view is tax hikes and slower economic growth ahead, but others argue that the current crisis can be overcome—if the economy remains strong.

Just as in a household, debt increases when expenditures exceed revenue. In the case of the government, revenue comes from taxes. The annual budget deficit is added to the national debt. A budget surplus can reduce the debt. A look at history provides some insight into the current nation debt.

For starters, the Founding Fathers had no fear of debt—in fact, they embraced it. A prime impetus for the formation of the United States was to create an entity that could borrow money, and it wasted no time in doing so. Just one year after the Constitution went into effect in 1789, the U.S. was already in debt.

Postcard of 'The Signing of the Declaration of Independence', painted by John Trumbull, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY

Postcard of 'The Signing of the Declaration of Independence', painted by John Trumbull, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTYIn 1929, the year the stock market crash started the Great Depression, the national debt totaled about $17 billion and the debt-to-GDP ratio was about 16%, according to U.S. Treasury Department figures.

In 1931, two years after the onset of the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl drought, detailed in John Steinbeck's novel The Grapes of Wrath, drove many people to California. The national debt totaled $17 billion and about 22% of a smaller economy.

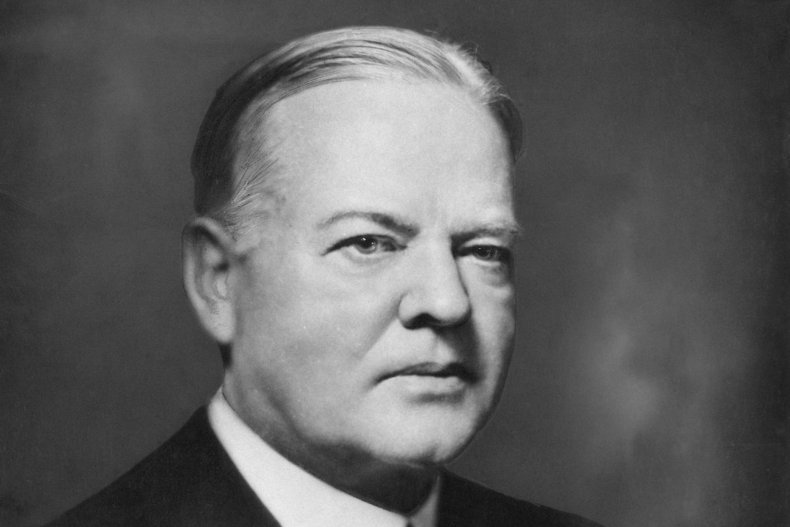

Herbert Hoover, 31st president of the United States, 1929-1933.EDWARD GOOCH, HULTON ARCHIVE, GETTY IMAGES

Herbert Hoover, 31st president of the United States, 1929-1933.EDWARD GOOCH, HULTON ARCHIVE, GETTY IMAGESOne-term Republican President Herbert Hoover raised taxes in 1932, his last year in office, and the economy continued to slow. The national debt increased to $20 billion or about 34% of GDP. President Franklin D. Roosevelt increased federal spending as part of the New Deal in 1933, and the national debt increased to $23 billion or about 40% of GDP.

As the U.S. re-armed to fight Germany, Italy and Japan in World War II, the debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 38% in 1941 to 67% in 1943, 90% in 1944 and 114% in 1945. The national debt increased more than five-fold during the war, growing from $49 billion in 1941 to $259 billion in 1945.

Despite recessions and the beginning of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, debt-to-GDP ratio declined from 103% in 1947 to 86% in 1950 when the Korean War started. In 1960, the last year of President Dwight Eisenhower's second term, the national debt totaled $286 billion and the debt-to-GDP ratio was 53%.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy's tax cuts boosted the economy and the debt-to-GDP ratio declined to 49% as the economy expanded, but the national debt grew to $298 billion. After John F. Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson raised spending for the War on Poverty and increased U.S. participation in the Vietnam War. A recession followed.

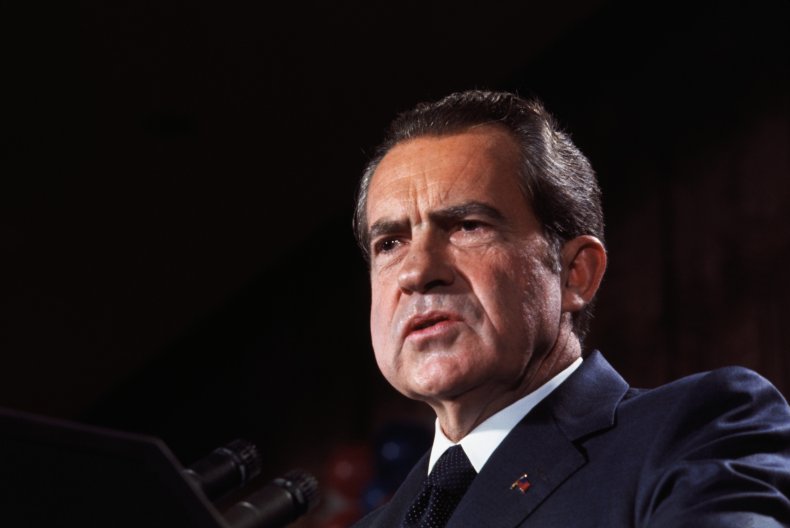

President Richard Nixon imposed wage and price controls in 1971 and stagflation (high inflation, high unemployment and low economic demand) soon followed. When Nixon voluntarily abandoned the gold standard and OPEC hiked prices in 1973, the national debt totaled $458 billion and the debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 32%.

President Richard Nixon makes victory speech at a rally shortly after being elected to serve a second term by a landslide in the 1972 Presidential election.BETTMANN/GETTY

President Richard Nixon makes victory speech at a rally shortly after being elected to serve a second term by a landslide in the 1972 Presidential election.BETTMANN/GETTYThe economy continued to stagnate under one-term Democratic President Jimmy Carter. That national debt ranged from $699 billion in 1977 to $908 billion in 1980. The debt-to-GDP ratio ranged from 32% to 34% during that period. In 1980, Carter's last year in office, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker raised the federal funds rate to 20% to tame inflation.

In 1981, President Ronald Reagan cut taxes to spur the economy as Kennedy had, but failed to control spending, and the U.S. posed its first trillion-dollar deficit in 1982. The debt-to-GDP ratio was 34% and it grew to 50% in 1988.

,

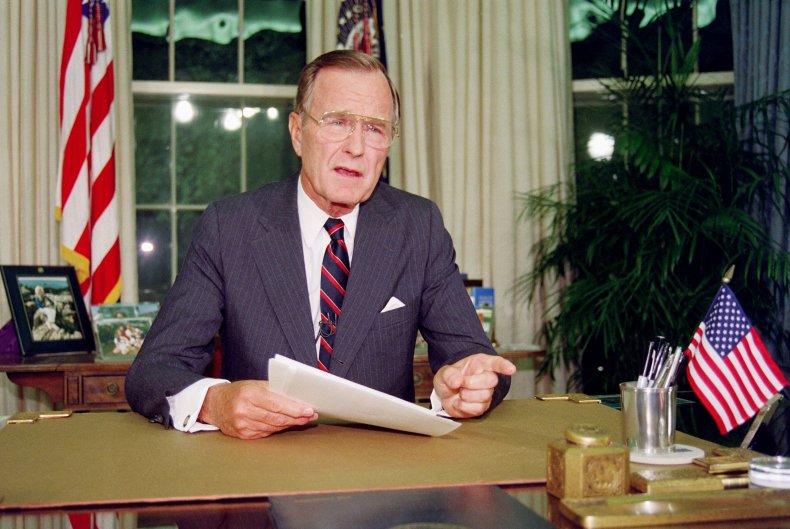

After the first Iraq war and a mild recession in 1991 during one-term Republican President George H.W. Bush's administration, the national debt rose to $4.065 billion and the debt-to-GDP ratio was 62%.

US President George H W Bush after his address to the nation, 27 September 1991, in the Oval Office of the White House.LUKE FRAZZA/AFP/GETTY

US President George H W Bush after his address to the nation, 27 September 1991, in the Oval Office of the White House.LUKE FRAZZA/AFP/GETTYDuring President Bill Clinton's two terms, the debt-to-GDP ratio fell from 64% in 1993 to 55% in 2000 and the budget deficit ranged from $4.411 trillion to $5.674 trillion in 2000, when the U.S. had a budget surplus, thanks in part to the "Dot Com" boom.

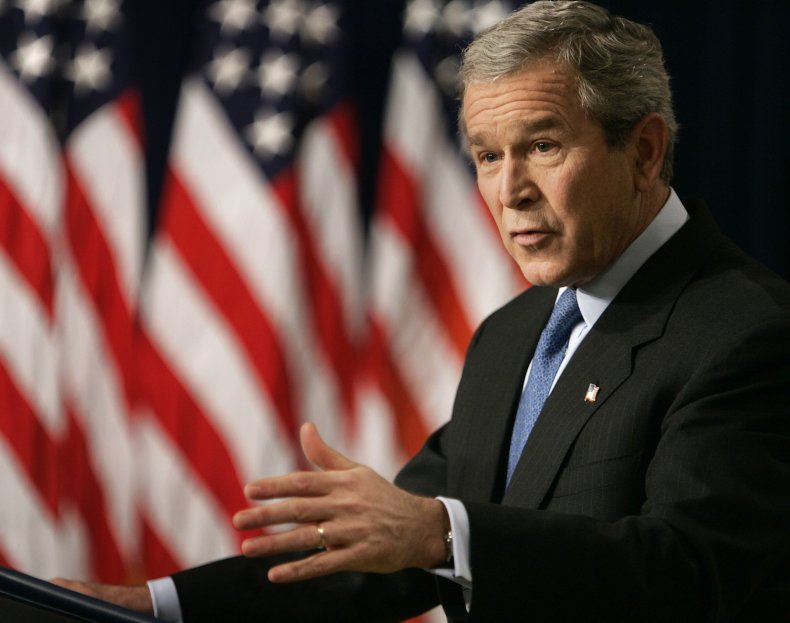

President George W. Bush used the budget surplus to justify a large tax cut in 2001, his first year in office, and followed that with another large tax cut in 2003. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonprofit research and policy institute, reported that the Bush tax cuts added $5.6 trillion to the deficit between 2001 and 2018, an amount equal to about one-third of the total federal debt in 2018.

U.S. President George W. Bush speaks during a news conference at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, December 20, 2004.MARK WILSON/GETTY IMAGES

U.S. President George W. Bush speaks during a news conference at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, December 20, 2004.MARK WILSON/GETTY IMAGESBush's two terms saw the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, the War on Terror, the second Iraq War, Hurricane Katrina, bank bailouts and the Fed's quantitative easing to support the economy. The national debt rose from $5.807 trillion in 2001 to $10.255 trillion in 2008 while the debt-to-GDP ratio ranged from 55% to 68% during that period.

The economy recovered slowly from the Great Recession of 2008 at the beginning of two-term Democratic President Barack Obama's first term, and the national debt increased from $11.901 trillion in 2009 to $19.573 trillion in 2016. The debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 82% to 104%.

During Republican President Donald Trump's one term, Congress raised the debt ceiling, he engaged in a trade dispute with China, cut taxes as Kennedy and Reagan had done, and approved massive federal spending to keep the economy afloat during the COVID-19 pandemic.

(L-R) Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Vice President Mike Pence listen as U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a signing ceremony for H.R. 748, the CARES Act in the Oval Office of the White House on March 27 in Washington, DC.PHOTO BY ERIN SCHAFF-POOL/GETTY

(L-R) Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) and Vice President Mike Pence listen as U.S. President Donald Trump speaks during a signing ceremony for H.R. 748, the CARES Act in the Oval Office of the White House on March 27 in Washington, DC.PHOTO BY ERIN SCHAFF-POOL/GETTYDuring Trump's term, the national debt increased from $20.245 trillion in 2017 to about $26.477 trillion, and the debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 104% to about 136% of an economy undercut by the coronavirus pandemic, an increase of about 31%.

Reducing the national debt is a pain now/gain later proposition—and a hard sell politically.

Writing for the Brookings Institution, Stuart Butler, a senior fellow for economic studies at the Washington-based think tank, explained why millennials aren't concerned about the national debt.

"Few young Americans have any direct experience with significant inflation and high interest rates" Butler wrote. "So scary scenarios that bring back chilling and real memories for [Baby Boomers] don't elicit a visceral reaction from them."

He said other more dramatic issues, such as the environment, seem to capture their attention.

"They've seen devastating hurricanes and tsunamis and the disappearance of coral reefs, Butler wrote. "Climate change seems very real. Debt-triggered economic problems do not."

No comments:

Post a Comment