[Editor’s Note: Mad Scientist welcomes back returning guest blogger Dr. Nick Marsella, former Devil’s Advocate/Red Team for the U.S. Army’s Training and Doctrine Command. In today’s post, Dr. Marsella explores the importance of national will — “the people’s acceptance of loss of treasure (money, focus on other priorities, and people) to accomplish some national objective.” This fickle and oftentimes ephemeral variable plays a paramount role in our democracy’s national security calculus. Read on to learn how this critical, yet fragile component of national power is increasingly threatened by hyperpolarization fueled by errors in perception, biases, and deliberate deception.]

The Theory

Even if the United States has a superior military force equipped with the most futuristic, sophisticated and technologically advanced weapons – without the national will to persevere on a course of action – the United States will fail to achieve its objectives or worse – lose a future conflict. As many classic strategists and military theoreticians have noted, war is a human endeavor requiring some degree of consensus on the political and military goals being advocated and a corresponding degree of “national will” to expend treasure to achieve them. Clear and attainable objectives with popular and international support are key ingredients necessary for success.1 This is especially true for a democratic society.

The Problem

Since the founding of the republic, Americans have been often been divided in their views of what policies the nation should adapt in its domestic and international affairs. Yet today, America seems more polarized than ever – with  some commentators even speculating that we are now in a cold “civil war – an era of hyperpolarization.” While time and future political scientists/historians will judge the accuracy of this perception, it is my contention that increased polarization in the near and far future could result in the nation becoming incapable of achieving a consensus on many long-term national security objectives and policies and becoming just as incapable of massing the national will to see an objective through to the end.

some commentators even speculating that we are now in a cold “civil war – an era of hyperpolarization.” While time and future political scientists/historians will judge the accuracy of this perception, it is my contention that increased polarization in the near and far future could result in the nation becoming incapable of achieving a consensus on many long-term national security objectives and policies and becoming just as incapable of massing the national will to see an objective through to the end.

some commentators even speculating that we are now in a cold “civil war – an era of hyperpolarization.” While time and future political scientists/historians will judge the accuracy of this perception, it is my contention that increased polarization in the near and far future could result in the nation becoming incapable of achieving a consensus on many long-term national security objectives and policies and becoming just as incapable of massing the national will to see an objective through to the end.

some commentators even speculating that we are now in a cold “civil war – an era of hyperpolarization.” While time and future political scientists/historians will judge the accuracy of this perception, it is my contention that increased polarization in the near and far future could result in the nation becoming incapable of achieving a consensus on many long-term national security objectives and policies and becoming just as incapable of massing the national will to see an objective through to the end. This recent rise in hyperpolarization is partially due to the rise and misuse of social media and news outlets; distrust of the press, academia, and expertise; the increase of sophisticated foreign influence operations to shape US public perceptions; and the lack of confidence in agencies and departments of government. The critical question is what impact this increased division in the body politic has on our ability to exert power in the national security arena in the near and far future?

This recent rise in hyperpolarization is partially due to the rise and misuse of social media and news outlets; distrust of the press, academia, and expertise; the increase of sophisticated foreign influence operations to shape US public perceptions; and the lack of confidence in agencies and departments of government. The critical question is what impact this increased division in the body politic has on our ability to exert power in the national security arena in the near and far future?Importance of National Will to National Power USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) leads a formation of Carrier Strike Group Five ships as U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress aircraft and U.S. Navy F/A-18s pass overhead / Source: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Erwin Miciano

USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) leads a formation of Carrier Strike Group Five ships as U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress aircraft and U.S. Navy F/A-18s pass overhead / Source: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Erwin Miciano

USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) leads a formation of Carrier Strike Group Five ships as U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress aircraft and U.S. Navy F/A-18s pass overhead / Source: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Erwin Miciano

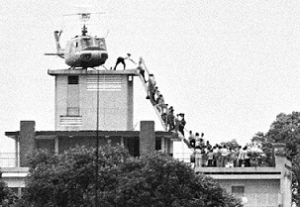

USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) leads a formation of Carrier Strike Group Five ships as U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress aircraft and U.S. Navy F/A-18s pass overhead / Source: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Erwin MicianoDetermining a nation’s power is part art and science. As David Jablonsky noted: “National power is contextual in that it can be evaluated only in terms of all the power elements and only in relation to another player or players and the situation in which power is being exercise.” He further noted: “A nation may appear powerful because it possesses many military assets, but the assets may be inadequate against those of a potential enemy or inappropriate to the nature of the conflict. The question should always be: power over whom, and with respect to what?”2 Iconic image of evacuees boarding an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street on April 29, 1975, shortly before Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese troops. / Source: UPI/Newscom via Wikipedia , Photo by Hugh Van Es

Iconic image of evacuees boarding an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street on April 29, 1975, shortly before Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese troops. / Source: UPI/Newscom via Wikipedia , Photo by Hugh Van Es

Iconic image of evacuees boarding an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street on April 29, 1975, shortly before Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese troops. / Source: UPI/Newscom via Wikipedia , Photo by Hugh Van Es

Iconic image of evacuees boarding an Air America helicopter on the roof of 22 Gia Long Street on April 29, 1975, shortly before Saigon fell to advancing North Vietnamese troops. / Source: UPI/Newscom via Wikipedia , Photo by Hugh Van EsSimply possessing overwhelming military and economic power is often insufficient to calculating the winner or loser in a conflict – such as illustrated with US involvement in Vietnam. As J.J. Kubiak noted: “The bigger truth is that the decision to leave Vietnam as a loser was a policy decision made not of military necessity, nor dictated by circumstances in the international environment, but because the U.S. had simply lost its political will to persevere.”3

Even during WW II with overwhelming public support to defeat Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, General Marshall recognized time was also his enemy as war weariness set in with political and economic support waning with a corresponding demand for demobilization as early as 1943 and accelerating after VE day.4

There are many definitions and ways to look at national will as reflected in the literature. For the military professional, the term “national will to fight” is probably familiar. RAND defines it as the “determination of a national government to conduct sustained military and other operations for some objective even when the expectation of success decreases or the need for significant political, economic, and military sacrifices increases.”5 I would suggest the term “national will” should be more expansive aligned to the “degree of determination in the pursuit of its internal or external objectives” (as noted by Jablonsky). Bottom line – national will is the people’s acceptance of loss of treasure (money, focus on other priorities, and people) to accomplish some national objective – whether it is to put a man on the moon, develop a cure for a disease, or fight and win a war.

Considerations for the Futurist and Future StudyPresident Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats connected Americans to the White House in a way no medium of communication had yet allowed. / Source: Library of Congress via The White House Historical Association

There are few hard and fast rules concerning national will for the current or future strategist to consider in the formulation of long-term national security objectives or policies. First, for a policy or objective to be successful, national will, especially in a democracy, must be present. The public must be continually educated by public officials on the importance and needed sacrifices to advance US national interests with as much transparency as the situation allows. Franklin D. Roosevelt understood this – famously hosting his Fireside Chats. These public informal conversational addresses given about twice a year were designed to inform, defend government programs, encourage, and request popular support.6

The Chinese understand this point about educating the public. While April 15th in the US is “Tax Day,” in China it marks “National Security Education Day” – designed to increase public awareness and support on issues affecting their national security.7 While it would be difficult to see the US conducting a similar event, it is possible for US public officials to conduct frequent, honest and candid discussions on important national issues with rigorous but civil public debates. Somehow, discussions of important national security issues must move out of the “beltway” to capture the interest of “Main Street America.” While Twitter and similar social media tools are powerful, they often present simplistic answers to complex questions.

The Chinese understand this point about educating the public. While April 15th in the US is “Tax Day,” in China it marks “National Security Education Day” – designed to increase public awareness and support on issues affecting their national security.7 While it would be difficult to see the US conducting a similar event, it is possible for US public officials to conduct frequent, honest and candid discussions on important national issues with rigorous but civil public debates. Somehow, discussions of important national security issues must move out of the “beltway” to capture the interest of “Main Street America.” While Twitter and similar social media tools are powerful, they often present simplistic answers to complex questions. U.S. Army Soldiers from 6th Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, Task Force Duke move towards a mission objective during Operation Tofan 2 in Suri Khel, Afghanistan, Sept. 15, 2011. The mission objective was to clear insurgents from the town of Suri Khel and prevent them from returning. / Source: U.S. Army; Photo by Sgt. Joseph Watson

U.S. Army Soldiers from 6th Squadron, 4th Cavalry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, Task Force Duke move towards a mission objective during Operation Tofan 2 in Suri Khel, Afghanistan, Sept. 15, 2011. The mission objective was to clear insurgents from the town of Suri Khel and prevent them from returning. / Source: U.S. Army; Photo by Sgt. Joseph WatsonSecond, time is a critical element in our calculus of the national will. History clearly indicates the American public is willing to make sacrifices to accomplish important strategic objectives (e.g., Soviet containment during the Cold War), but history also demonstrates the public can become impatient over time. For example, public support for US involvement in Afghanistan has continually fallen over the years. For example, by 2018 only 45% said it was the right decision to commit U.S. Soldiers, whereas 39% said it was a wrong decision – even though the committed number of Soldiers from a “professional volunteer force” were low and the costs of the war largely invisible to the public at large.8

A number of recent studies highlighted several trends which contribute to hyperpolarization and our degraded factual discourse to include: an “increasing disagreement about objective facts, data, and analysis; a blurring  of the line between fact and opinion; an increasing relative volume of opinion over fact; and declining trust in government, media, and other institutions that used to be sources of factual information.”9 American’s increasingly draw their information from non-traditional news sources and from cable news which as a RAND study noted “exhibited dramatic and quantifiable shift toward subjective, abstract, directive, and argumentative language, with content based more on the expression of opinion than on the provision of facts.”10

of the line between fact and opinion; an increasing relative volume of opinion over fact; and declining trust in government, media, and other institutions that used to be sources of factual information.”9 American’s increasingly draw their information from non-traditional news sources and from cable news which as a RAND study noted “exhibited dramatic and quantifiable shift toward subjective, abstract, directive, and argumentative language, with content based more on the expression of opinion than on the provision of facts.”10

of the line between fact and opinion; an increasing relative volume of opinion over fact; and declining trust in government, media, and other institutions that used to be sources of factual information.”9 American’s increasingly draw their information from non-traditional news sources and from cable news which as a RAND study noted “exhibited dramatic and quantifiable shift toward subjective, abstract, directive, and argumentative language, with content based more on the expression of opinion than on the provision of facts.”10

of the line between fact and opinion; an increasing relative volume of opinion over fact; and declining trust in government, media, and other institutions that used to be sources of factual information.”9 American’s increasingly draw their information from non-traditional news sources and from cable news which as a RAND study noted “exhibited dramatic and quantifiable shift toward subjective, abstract, directive, and argumentative language, with content based more on the expression of opinion than on the provision of facts.”10

While some of these findings about the press can be found in other American historical periods (e.g., 1890s yellow journalism) these were primarily motivated by a need to create or increase profit. However, many of today’s “free” online sources are more designed to reinforce existing opinions or camouflage opinions and untruths as facts – a trend that RAND has appropriately called – “Truth Decay.” The use of artificial intelligence to create “deepfake” videos and news will only add to the dilemma of finding “true facts.”

While space in this blog doesn’t allow a full discussion of how to treat “truth decay,” education may be part of the answer. For example, the Association of American Colleges and Universities has advocated for its members to examine how critical thinking, inquiry and analysis and other important skills are integrated and taught at the collegiate level.11 Others, such as H.R. McMaster advocate expanding “history and civics” education within our primary and secondary schools to instill confidence in the “great unfinished American experiment in democracy and liberty.”12 We also need to expand our discussion of “truth decay” as part of professional military and civilian education and examine how we educate/train critical thinking and inquiry and analysis within our own Government-run schoolhouses.

Another important factor contributing to this problem is external to the US. Throughout history, competitors and adversaries have used information to shape the perception and decision making of political and military leaders and populations to their favor.13 Today, as in the future, foreign influence operations will take different forms, but all are designed with similar purposes. As highlighted in recent testimony by the Director FBI on “Worldwide Threats to the Homeland,” other nations “conduct disinformation campaigns and foreign influence operations in an effort to mislead, sow discord, and, ultimately,

Another important factor contributing to this problem is external to the US. Throughout history, competitors and adversaries have used information to shape the perception and decision making of political and military leaders and populations to their favor.13 Today, as in the future, foreign influence operations will take different forms, but all are designed with similar purposes. As highlighted in recent testimony by the Director FBI on “Worldwide Threats to the Homeland,” other nations “conduct disinformation campaigns and foreign influence operations in an effort to mislead, sow discord, and, ultimately,  undermine confidence in our democratic institutions and values…” Wray further noted attempts using false personas and fabricated stories on social media platforms to discredit U.S. institutions and individuals by agents outside the United States.14

undermine confidence in our democratic institutions and values…” Wray further noted attempts using false personas and fabricated stories on social media platforms to discredit U.S. institutions and individuals by agents outside the United States.14Foreign influence operations will most likely grow and become more sophisticated in the future. For example, since 2003, China has emphasized development of its “Three Warfares” concept of physiological, public opinion,  and legal warfare using cyberspace and influence operations of cultural institutions, media, business, academia and policy communities in the US. China has developed its “50 Cent Army” designed to spread party approved narratives abroad via social media.15

and legal warfare using cyberspace and influence operations of cultural institutions, media, business, academia and policy communities in the US. China has developed its “50 Cent Army” designed to spread party approved narratives abroad via social media.15

and legal warfare using cyberspace and influence operations of cultural institutions, media, business, academia and policy communities in the US. China has developed its “50 Cent Army” designed to spread party approved narratives abroad via social media.15

and legal warfare using cyberspace and influence operations of cultural institutions, media, business, academia and policy communities in the US. China has developed its “50 Cent Army” designed to spread party approved narratives abroad via social media.15Final Thoughts

National will is a fickle thing. It may be increasingly more difficult in the future to capture the consensus of the American people on courses of action to take on important national security issues given the growing lack of trust in our institutions of government, academia, and the news media as well as the apparent lack of ability to agree on the basic facts surrounding an issue. Even if a consensus is gained, it can be quickly lost due to perception, errors, or deliberate deception.

The evidence of increased hyperpolarization today is apparent when even during a global pandemic, wearing a face mask has become for some a partisan political issue and where only 6 of 10 Americans [as of November 17, 2020 Gallup Poll] are willing to trust and take a COVID-19 vaccine.16 We must face reality that we exist in a world with “alternative facts.” Strategists  and policy makers must understand the increased impact of “mainstream” social media (e.g., Twitter/Facebook), the potential growth of alternative social media,17 and the implications of AI and other unknown future technological advances to shape opinion and perception, which in turn will affect the nation’s ability to gain a consensus or support for a long-term policy. We shouldn’t forget the importance of will to gain consensus or support on a policy issue or to maintain the grit to see a course of action through; for as Võ Nguyên Giáp, Commander, People’s Army of Vietnam noted long ago: “In war there are two factors—human beings and weapons. Ultimately, though, human beings are the decisive factor. Human beings! Human beings!“18

and policy makers must understand the increased impact of “mainstream” social media (e.g., Twitter/Facebook), the potential growth of alternative social media,17 and the implications of AI and other unknown future technological advances to shape opinion and perception, which in turn will affect the nation’s ability to gain a consensus or support for a long-term policy. We shouldn’t forget the importance of will to gain consensus or support on a policy issue or to maintain the grit to see a course of action through; for as Võ Nguyên Giáp, Commander, People’s Army of Vietnam noted long ago: “In war there are two factors—human beings and weapons. Ultimately, though, human beings are the decisive factor. Human beings! Human beings!“18

and policy makers must understand the increased impact of “mainstream” social media (e.g., Twitter/Facebook), the potential growth of alternative social media,17 and the implications of AI and other unknown future technological advances to shape opinion and perception, which in turn will affect the nation’s ability to gain a consensus or support for a long-term policy. We shouldn’t forget the importance of will to gain consensus or support on a policy issue or to maintain the grit to see a course of action through; for as Võ Nguyên Giáp, Commander, People’s Army of Vietnam noted long ago: “In war there are two factors—human beings and weapons. Ultimately, though, human beings are the decisive factor. Human beings! Human beings!“18

and policy makers must understand the increased impact of “mainstream” social media (e.g., Twitter/Facebook), the potential growth of alternative social media,17 and the implications of AI and other unknown future technological advances to shape opinion and perception, which in turn will affect the nation’s ability to gain a consensus or support for a long-term policy. We shouldn’t forget the importance of will to gain consensus or support on a policy issue or to maintain the grit to see a course of action through; for as Võ Nguyên Giáp, Commander, People’s Army of Vietnam noted long ago: “In war there are two factors—human beings and weapons. Ultimately, though, human beings are the decisive factor. Human beings! Human beings!“18

No comments:

Post a Comment