By Chris Buckley

In one Beijing artist’s recent depiction of the world in 2098, China is a high-tech superpower and the United States is humbled. Americans have embraced communism and Manhattan, draped with the hammer-and-sickle flags of the “People’s Union of America,” has become a quaint tourist precinct.

This triumphant vision has resonated among Chinese.

The sci-fi digital illustrations by the artist, Fan Wennan, caught fire on Chinese social media in recent months, reflecting a resurgent nationalism. China’s authoritarian system, proponents say, is not just different from the West’s democracies, it is also proving itself superior. It is a long-running theme, but China’s success against the pandemic has given it a sharp boost.

“America isn’t that heavenly kingdom depicted since decades ago,” said Mr. Fan, who is in his early twenties. “There’s nothing special about it. If you have to say there’s anything special about it now, it’s how messed up it can be at times.”

China’s Communist Party, under its leader, Xi Jinping, has promoted the idea that the country is on a trajectory to power past Western rivals.

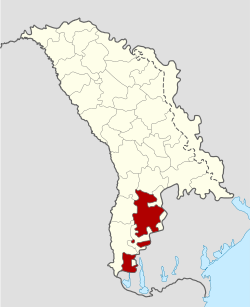

Gagauzia (red) in Moldova (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Gagauzia (red) in Moldova (Source: Wikimedia Commons)