By: Anita Inder Singh

Introduction

Following Chinese intrusions into India’s northern territory of Ladakh beginning in June (China Brief, July 15), relations between the two countries have seen a major downturn. Two strands of official Chinese thinking have emerged from statements by People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, as represented by PRC Foreign Minister Wang Yi (王毅) and PRC Ambassador Sun Weidong (孙卫东) in New Delhi: that Beijing does not offer any prospect of an early settlement to the border dispute, and that it accuses India of infringing on China’s territorial sovereignty. Wang Yi maintains that the Sino-Indian boundary between China and India “has not yet been demarcated,” and that China will firmly safeguard its sovereignty and territorial integrity (Global Times, September 1). Sun Weidong asserts the official PRC line that there has been no Chinese transgression in Ladakh, and that the disputed territory belongs to China (PRC Embassy in India, August 28).

Despite earlier flare-ups such as the 2017 Doklam crisis, New Delhi in recent years has viewed India’s politico-economic connection with China through rose-colored glasses. At the Wuhan (2018) and Chennai (2019) summits Prime Minister Narendra Modi saw a Sino-Indian strategic convergence at hand (Indian Ministry of External Affairs, April 28, 2018; Xinhua, April 29, 2018). In Chennai he reportedly envisioned “a beautiful future” for India-China relations (Xinhua, October 13, 2019). For his part, President Xi Jinping has urged the elephant and the dragon to further align their development strategies and to build a partnership in manufacturing industries.

In response to the recent border incidents, the Indian government has looked to restrict Chinese investment in India, and there have been public calls for boycotts of Chinese-made goods. However, this has highlighted the disparity in economic power between the two countries, as well as the extent to which India is dependent on Chinese goods. Ambassador Sun, and commentaries in PRC state media, continually highlight India’s economic weakness, the ultranationalism that its widespread poverty allegedly inspires, and the difficulties it faces in overcoming its problems as one of the countries most affected by COVID-19. The Global Times editorialized this summer that the “gap between China’s and India’s strength is clear” (Global Times, June 17; Global Times, August 27).

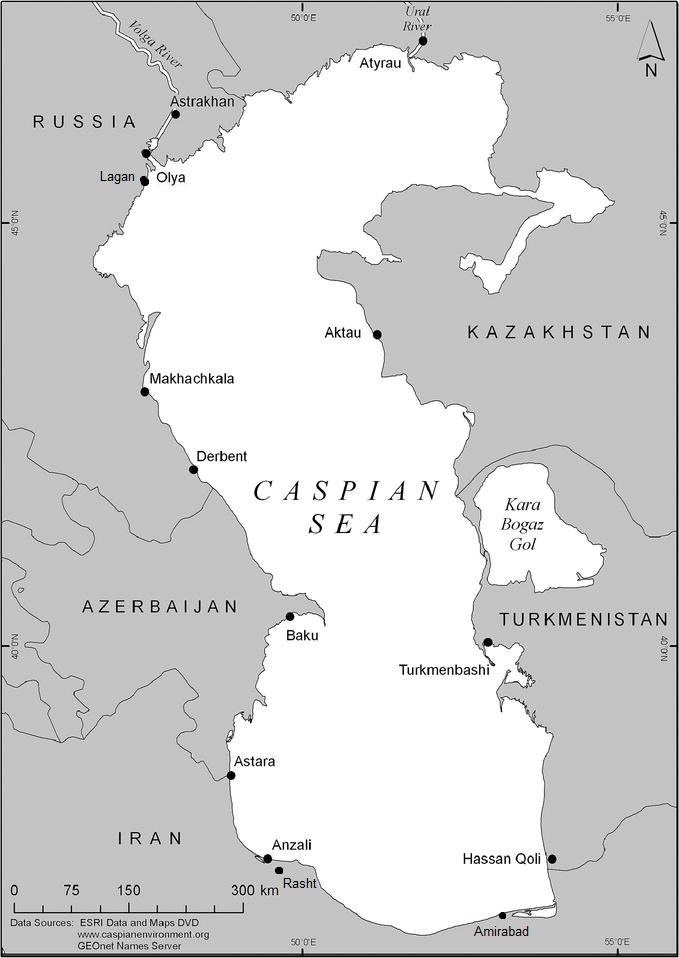

(Source: Brill)

(Source: Brill)