By Namrata Goswami

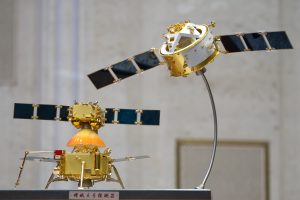

The Chang’e 5 returner, carrying about 2 kilograms of lunar rocks and soil, has successfully landed in Siziwang Banner in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region on December 17 local time. The Chang’e 5 followed upon the Chang’e 4 far side landing in January 2019 and has successfully accomplished some of China’s most technologically difficult feats yet. This included collecting the samples of lunar regolith, not only on the lunar surface but from six feet under; gathering the samples and sealing it in automated operations; and finally ascending from the lunar surface and docking with the orbiter waiting 200 km above. As per the China National Space Administration (CNSA), the ascender then transferred the samples to the returner, for which China utilized an autonomous grabbing machine.

Developing lunar access and presence capacity is vital to China’s conception of space power, which I define as the ability to persuade or coerce countries to behave in a manner in space that is beneficial to the country wielding space power. Space power consists of an ability to demonstrate space presence, independently launch to orbit and beyond, project and maintain military space power, and enable access to key zones in space to include the moon and the Lagrange points. For China, the Moon is a pit stop or a base to enable it to become a truly space faring nation, reflecting civilizational vibrancy, ideological superiority, and technical prowess. Based on this, there are three reasons why China is going to the moon.

Reason 1: The Moon Is a Tremendous Supplier of Energy

It was persistent advocacy from lead space scientist Ouyang Ziyuan that led to the establishment of the China Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) and the resultant Chang’e 1 mission in 2007. In an interview to PLA Daily in 2002, Ouyang specified that “China’s long-term aim and task is to set up a base on the moon to tap and make use of its rich resources…” He further stated in 2003 that “the moon could serve as a new and tremendous supplier of energy and resources for human beings… whoever first conquers the moon will benefit first… we are also looking further out into the solar system – to Mars.” In 2003, the then-director of the CNSA, Luan Enjie, hinted that “the prospect for the development and utilization of the lunar potential mineral and energy resources provide resource reserves for the sustainable development of human society.”

The focus on the moon for its resources – like water ice, helium-3, and titanium – is a long-term ambition, especially highlighted by comments made at a time when China was yet to launch its first manned mission to Low Earth Orbit (in 2003) and before it was confirmed that there is water ice on the lunar poles by a NASA Minerology Mapper launched on India’s Chandrayaan 1 mission in 2008. Mining the resources on the moon was one of the primary motivations in 2002 when China’s lunar mission was at its early stages of conceptualization and conducting feasibility studies; that logic stands unchanged 18 years later, as it advances in its lunar mission capabilities. Subsequent missions to follow the Chang’e 5 are the Chang’e 6 lunar south pole sample return mission, the Chang’e 7 lunar south pole survey mission, and the Chang’e 8 technology test mission to establish a lunar research base by 2036.

Reason 2: Demonstrating China’s Space Capacity

China under President Xi Jinping aspires to demonstrate the superiority of its civilization based on self-reliance and indigenous innovation, especially in high technology sectors like space. To be able to accomplish difficult space missions, especially in lunar orbit, to include the Chang’e 5 mission that involved descending, ascending, and then returning to Earth demonstrates advanced space capacity. To ensure success for the Chang’e 5, Chinese space scientists and engineers conducted 661 simulated docking tests and 518 sample transfer tests since 2011, nearly 10 years spent in perfecting the process.

Such space technology demonstrations have direct consequences for how China is perceived to an attentive audience, to those countries that it wants to influence with its space prowess. Next year, China will attempt to accomplish another difficult mission on Mars, with its first independent attempt at entering Martian orbit, landing on its surface, and then sending out a rover, all in one mission. If successful, China will catch up with decades of U.S. Mars capacity and advantage in a single attempt.

Reason 3: China as the 21st Century Space Icon

China aspires to be the 21st century space icon. When the Chang’e 5 unfurled a Chinese flag on the lunar surface, the state-owned Global Times enthused, “The Chinese national flag shines an even brighter red from moon.” Once the flag was unfurled, the Global Times made it clear why it was so significant:

The Chinese flag that Chang’e 5 displayed officially became the first and only fabric national flag that has ever been placed on the moon in the 21st century…hailed as the fresh and new icon of human’s lunar exploration, the Chinese flag would inspire today’s mankind, just as Apollo 11 did, encourage and celebrate generations to make an endeavor to space…displaying a national flag on a celestial body represents the comprehensive strength and technological advancement of the country.

The Chinese lunar flag was developed by engineers at the China Space Sanjiang Group, a subsidiary company under the state-owned China Aerospace Science and Industry Corporation (CASIC). The designers of the flag specified that, “an ordinary national flag on Earth would not survive the severe lunar environment.” Therefore, a year was spent in selecting a fabric material for the flag that could withstand the extreme weather conditions on the lunar surface, to include cosmic radiation, since the moon has no protective atmosphere and magnetosphere.

Becoming the 21st century icon for space has long-term implications for China’s standing in international politics. Xi has made every effort since he took over power to ensure China is an assertive and dominant player in the world stage. As part of this, Xi’s diplomatic signature policy move is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which now includes 136 countries and 30 international institutions. Space is an integral part of the BRI and Chinese space competitiveness is drawing in members including countries in Europe like Italy and Luxembourg. The collaboration between the CNSA and the European Space Agency (ESA) with regard to the Chang’e 5 mission’s navigation support is a case in point. There is an incentive to collaborate with a China-led space order given the future economic benefits it promises, to includes resource investments in Europe’s under-funded new space sector. The more China demonstrates high end space technology, the more international partnerships it will attract.

Once China establishes an automated robotic base presence on the moon by 2036 followed by a human landing, with advanced capacities to mine the resources on the lunar surface, the world will watch with awe and surprise given such a presence is likely to be of a permanent nature.

In 2002, Ouyang Ziyuan articulated a vision of what has now become one of the world’s most advanced robotic lunar missions. Known as the “People’s Scientist,” Ouyang stated then that he was committed to succeed to help develop the Chinese nation. Today, China’s space sector is even more tightly controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. Its ideological narrative includes not just directing the future of the Chinese space program – via Document 60 issued by the State Council in 2014 – but even dictating how science fiction authors should project Chinese space power. Every kind of advanced technological development has to now occur under the systemic, holistic, and coordinated approach adopted by “Xi Jinping Thought,” with the aim to turn China into an authoritarian-led modern socialist country by 2035, with space as an integral component of that rise.

During his meeting with the Chang’e 4 engineers and scientists on February 21, 2019, after its successful landing on the lunar far side, Xi highlighted:

Experience tells us that great undertakings begin with dreams, and dreams are the source of vitality. China is a nation that pursues dreams bravely. The [CCP] Central Committee’s decision to implement the lunar exploration project is to pursue the nation’s unyielding dream of flying into the sky and reaching for the moon… In the journey of building a great modern socialist country and realizing the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, every industry and every person should dream and strive courageously and fulfill their dreams with arduous and continuous efforts, step by step and baton by baton just like in a relay race.

The next 20 years promises to be exciting as far as China is concerned with its growing sophistication in space. There are plans for a 2021 Mars landing, a permanent space station in 2022, a lunar south pole sample return mission in 2024, a 100kW space-based solar power (SBSP) demonstration at LEO in 2025, and a Mars sample return in 2028. In 2030 alone China plans to carry out a lunar north and south pole survey, launch the Long March 9 super heavy lifter, and conduct a 1 mW SBSP demonstration in GEO. In 2035, China will test key technologies like 3D printing to lay groundwork for the construction of a lunar base and set up 100 mW SBSP with electric power generating capacity. The plan is for a human mission to the moon in 2036 and establishment of a lunar research base, with a nuclear powered space fleet by 2040 and for China’s SBSP system to start generating power in the same year. Given China has met past space deadlines on time including the launch of the Mars mission and the Chang’e 5 lunar sample return in 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic, watch out for these future timelines.

Xi aspires to achieve an authoritarian-led space order with economic generosity and a carefully constructed narrative of “benefiting humankind.” Lurking behind that feel-good narrative, however, is a highly nationalistic and ambitious space program that aspires to establish China as the leading nation in space innovation by 2049. China’s sophisticated lunar capacity plays a critical role in achieving that goal. That is why the moon matters most.

Dr. Namrata Goswami is a senior analyst and author specializing in space policy, geopolitics and great powers. She is co-author of the book “Scramble for the Skies: The Great Power Competition to Control the Resources of Outer Space’” (2020, Lexington Press).

No comments:

Post a Comment