Taras Kuzio

European orientalism portrayed the ‘White Man’s Burden’ as the bringing of ‘civilisation’ and enlightenment to colonies. Meanwhile, the nationalisms of colonial peoples were depicted in highly negative ways, and their national liberation struggles were considered ‘treacherous’ and acts of ‘terrorism.’ An orientalist view of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ nationalisms (imperialism) is used by Western scholars when writing about the Russian-Ukrainian War. With a few exceptions (see Harris 2020), Russian nationalist involvement in the war is dismissed, completely ignored (see Clarke 2014, 50; Matveeva 2018, 182, 218, 221, 223, 224, 277), or downplayed as a temporary phenomenon (Kolsto 2016a, 6; Hale 2016, 246; Laurelle 2020a). Russian nationalists (imperialists), anti-Semites, and xenophobes, such as Aleksandr Dugin (2014), Vladyslav Surkov (2020), and Glazyev (2020), were leading figures in the 2014 ‘Russian spring’ and ‘New Russia’ (see Likhachev 2016; Laruelle 2016a; Shekhovtsov 2017). Russian chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians did not end in 2015–2016, and therefore it is unclear how Putin’s regime became less nationalistic after this date (Hale 2016; Laruelle 2020a). Since 2014, the Russian regime has become more nationalistic and chauvinistic, while nationalism in Ukraine has become more civic, and yet some western writing on Ukraine and Russia since 2014 gives the opposite impression.

This chapter is divided into five sections. The first section surveys how Russian nationalism (imperialism) is downplayed, minimised, or described as a temporary phenomenon. The second section analyses how western writing exaggerates the influence and evil nature of Ukrainian nationalism. The third section provides a historical comparison of why both Stalin and Putin had obsessions towards Ukraine and Ukrainians. The final two sections provide evidence of the rehabilitation of Tsarist and White émigré nationalism (imperialism), and how this influences chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians in official discourse, diplomatic relations, military aggression, and Russian information warfare.

In Search of Russian Nationalism (Imperialism)

Downplaying the influence of Russian nationalism (imperialism) in the USSR and contemporary Russia is not a recent phenomenon (see Gessen 2017, 52, 77–78), but rather existed long before the 2014 crisis in Russia’s inability to come to terms with an independent Ukraine going back to 1991 (D’Anieri 2019). Russians have always ‘felt Ukraine was an intrinsic part of Russia,’ which is deeply rooted in Russian identity (D’Anieri 2019, 2). The Russian-Ukrainian crisis is ‘deeper than is commonly understood’ because of a ‘profound normative disagreement and conflicts of interest’ (D’anieri 2019, 2).

Marginal nationalism became mainstream nationalism in Russia in the 2000s when the ‘emergence of a virulent nationalist opposition movement took the mainstream hostage’ (Clover 2016, 287). In downplaying nationalism in Russia’s political system, scholars ignore the hyper-nationalism (imperialism) underpinning Russia’s authoritarian political system, including in the United Russia Party, as well as nationalist party projects that have received state support, such as the LDPR and Rodina.

Matveeva (2018) sidesteps the political affiliations of the Russian leaders of Donbas separatists in spring 2014 because to do so would show that Russian neo-Nazis and other similar extremists were in charge and therefore what was taking place could not be described as a ‘civil war’ (Kolsto 2016b, 16). Matveeva (2018, 224) disagrees with Laruelle’s (2016) analysis of Russian nationalist (imperialist) alliance during the ‘Russian spring’ between ‘brown’ (fascist), ‘white’ (monarchist and Orthodox fundamentalist), and ‘red’ (Communist) politicians. At the same time, Matveeva (2018, 97) herself writes that volunteers from Russia consisted of ‘nationalists, monarchists, spiritual heirs of ‘White Russia,’ ultra-leftists, National Bolsheviks, and Communists.’

Matveeva (2018) makes no mention of the presence of the neo-Nazi RNE (Russian National Unity) Party although there are many photographs of their military activities in eastern Ukraine and their taking up leadership positions in the 2014 ‘Russian spring’ (Shekhovtsov 2014). Pavel Gubarev, Donetsk ‘People’s Governor’ in spring 2014, is one of Matveeva’s (2018, 182) sources of information, and she describes him as one of the ‘uprising’s original ideologues.’ Gubarev’s colleagues, Alexander Borodai and Alexander Prokhanov, edit the fascist, Stalinist, and nationalist (imperialist) newspaper Zavtra (Tomorrow), which began as the Den (The Day) newspaper in 1990. Prokhanov supported the August 1991 hardline anti-Gorbachev coup and wrote its manifesto, ‘A Word to the People.’ Den supported the 1993 hardline coup against Yeltsin. National Bolshevik anti-Semite Glazyev is a long-time contributor to Zavtra.

Borodai is quoted by Matveeva (2018, 218) as saying that Russian leaders provided the ‘organizational, ideological’ support to the ‘Russian spring.’ In late February 2014, Russian intelligence assisted the neo-Nazi RNE Party to establish a branch in Donetsk (Likhachev 2016, 22). Not coincidentally, on 1 March 2014, the day pro-Russian uprisings were organised by Russian intelligence in 11 cities in southeastern Ukraine, the Donetsk Republic organisation installed former RNE Party member Gubarev as ‘People’s Governor’ (Na terrritorii Donetskoy oblasty deystvovaly voyennye lagerya DNR s polnym vooruzheniyem s 2009 goda 2014).

Local journalists reported the arrival of Russian neo-Nazis in spring 2014 in the Donbas.[2] A Ukrainian blogger from Donetsk wrote: ‘The skinheads dressed uniformly were clearly not local. Here shaved heads and bomber jackets have long gone out of fashion with those on the right’ (Coynash 2014). The Black Hundreds organisation, RNE Party, Other Russia and its Interbrigades (Donbass), Girkin’s Russian Imperial Movement (labelled by the US as a terrorist organisation in April 2020), Shield of Moscow, Russian Orthodox Army, and Rusich participated in the Donbas conflict from its inception.

Eurasianist and neo-fascist Dugin, a professor at Moscow State University and adviser to State Duma speaker Sergei Naryshkin, strongly backed the ‘uprisings,’ describing them as a ‘sacrificial awakening of Russia’ and a ‘magnificent uprising of the Russian soul ‘against ‘petty, crude nationalism of Galicia’ (Fitzpatrick 2014). In June 2014, Dugin (2014) called for Ukrainians to be ‘killed, killed, killed’ in what can only be called an extreme example of racism and Russian chauvinism.

Vyacheslav Likhachev (2016, 22), Ukraine’s pre-eminent authority on anti-Semitism and xenophobia in Ukraine, writes that ‘Russian nationalists were far more prominent than Ukrainian nationalists at the beginning of the conflict.’ Likhachev (2016, 22) argues, ‘It is hardly likely, however, that the Kremlin-inspired ‘separatist’ rebellion in the Donbas would have played out in the way it did had Russian extreme nationalists not taken part.’ The three ‘most visible’ leaders of the DNR at its inception were Russian citizens ‘with varying degrees of connection to the intelligence services of Russia’ (Bowen 2019, 329).

Academic orientalism describes Russian nationalists (imperialists) as ‘patriots’ and western-style ‘conservatives’ – only Ukrainians are ‘nationalists.’ Borodai is described by Matveeva (2018, 95) as a ‘Russian conservative thinker.’ Gubarev’s and Borodai’s membership in the neo-Nazi RNE Party is ignored (see Shekhovtsov 2014) and instead they are described as ‘patriots’ and ‘conservatives.’ Remarkably, Matveeva (2018, 221, 223) cannot find any evidence of extreme-right nationalism in Borodai. Laruelle (2020a, 126) writes that ‘the Putin regime still embodies a moderate centrist conservatism.’ Petro (2018) talks of a ‘conservative turn’ in Russian foreign policy (see also Sakwa, 2020b, 276–277; Robinson 2020, 284–285, 287, 289, 293, 299).

If British conservatives annexed part of Ireland and denied the existence of Irish people, they could no longer be called conservatives. Similarly, Putin’s regime’s annexation of Crimea and denial of the existence of Ukraine and Ukrainians has nothing to do with conservatism.

Sakwa (2017a) and Matveeva (2018) only find ‘militarised patriotism’ (Sakwa 2017,119) or elites divided into ‘westerners’ and ‘patriots’ (Matveeva 2018, 277). Following his 2012 re-election, Putin spoke of ‘Russian identity discourse’ (Sakwa 2017a, 189), while his ‘conservative values’ are not the same as a nationalist agenda (Sakwa 2017a, 125). Western political scientists working on Russia have a very flexible definition of conservatism. Putin was not dependent upon Russian nationalism, ‘and it is debatable whether the word is even applicable to him,’ Sakwa (2017a, 125) writes.

Sakwa (2017a) is simply unable to ever use the term ‘nationalist’ when discussing Russian politicians, while at the same time undertaking orientalist somersaults to downplay Russia’s support for populist-nationalists and neo-Nazis in Europe. Russia’s European allies are described as ‘anti-systemic forces,’ ‘radical left,’ ‘movements of the far right,’ ‘European populists,’ ‘traditional sovereigntists, peaceniks, anti-imperialists, critics of globalization,’ ‘populists of left and right,’ and ‘values coalition’ (Sakwa 2017a, 275, 276, 60,75). Sakwa (2020a) writes that, ‘Anton Shekhovtsov (2017) is mistaken to argue that Russia’s links to right-wing national populist movements are rooted in philosophical anti-Westernism and an instinct to subvert the liberal democratic consensus in the West. In fact, the alignment is situational and contingent on the impasse in Russo-Western relations and thus is susceptible to modification if the situation changes.’ Russian support for fascists, neo-Nazis, Trotskyists, Stalinists, and racists in Europe and the US are ignored or excused (Shekhovtsov 2018), as are the hundreds of members of Europe’s extreme right and extreme left who have joined Russian proxy forces in the Donbas.

Sakwa (2017a, 159) writes that ‘the genie of Russian nationalism was firmly back in the bottle’ by 2016. Kolstø (2016) and Laruelle (2017a) write that the nationalist rhetoric of 2014 was novel and subsequently declined, while Henry Hale (2016) also believes Putin was only a nationalist in 2014, not prior to the annexation of the Crimea or since 2015. Laruelle (2020a, 126) concurs, writing that by 2016, Putin’s regime had ‘circled back to a more classic and pragmatic conservative vision. Conservatism again. Laruelle (2020b, 348) describes Putin’s regime as nationalistic only between 2013-2016 and ‘since then has been curtailing any type of ideological inflation and has adopted a low profile, focusing on much more pragmatic and Realpolitik agendas at home and abroad.’ ‘Putin is not a natural nationalist’ and ‘[w]e do not see the man and the regime as defined by principled ideological nationalism’ (Chaisty and Whitefield 2015, 157, 162). Putin is not an ideologue because he remains rational and pragmatic (Sakwa 2015, 2017) and therefore not a Russian nationalist.

Rehabilitating White Émigrés and Fascists

Putin’s rehabilitation of the White émigré movement and reburial of its officers and philosophers in Russia is not a sign of conservatism, but of nationalism (imperialism). It is not a coincidence that these reburials took place at the same time as the formation of the Russian World Foundation (April 2007) and unification of the Russian Orthodox Church with the émigré Russian Orthodox Church (May 2007). Putin personally paid for the re-burial in Russia of White émigré nationalists (imperialists) and fascists Ivan Ilyin, Ivan Shmelev, and General Anton Deniken. All three deny the existence of a Ukrainian nation. Ilyin’s chauvinistic views of Ukraine and Ukrainians are typical of Russian White émigrés (see Wolkonsky 1920; Bregy and Obolensky 1940). As Plokhy (2017, 327) writes, ‘Russia was taking back its long-lost children and reconnecting with their ideas.’

Putin is ‘particularly impressed’ with Ilyin whom Timothy Snyder (2018) defines as a fascist. Putin first cited Ilyin in an address to the Russian State Duma in 2006 (Plokhy 2017, 327). Putin has recommended Ilyin to be read by his governors, former senior adviser Surkov, and Prime Minister Medvedev. Ilyin’s publications will be used in the Russian state programme, inculcating ‘patriotism’ and ‘conservative values’ in Russian children (Sukhankin 2020). Ilyin was integrated into Putin’s ideology during his re-election campaign in 2012 and influenced Putin’s re-thinking of himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands’ and as bringing Ukraine back into the Russian World (Snyder 2018; Plokhy 2017, 332).

Laruelle (2017b) downplays the importance of Ilyin’s ideology, writing that he did not always propagate fascism and Putin only quoted him five times. It is difficult to understand how our concerns are supposed to be ameliorated because Putin cited a Russian nationalist (imperialist) and fascist sympathiser only five times. Putin not only cited Ilyin, but also asked Russian journalists whether they had read Deniken’s diaries, especially the parts where ‘Deniken discusses Great and Little Russia, Ukraine’ (Plokhy 2017, 326). Deniken wrote in his diaries, ‘No Russian, reactionary or democrat, republican or authoritarian, will ever allow Ukraine to be torn away’ (Plokhy 2017, 326). Putin evidently agrees with Ilyin, Deniken, and other White émigrés about the non-existence of a Ukrainian nation.

If we apply Laruelle’s (2017a) logic to Organisation of Ukrainian nationalist (OUN) leader Stepan Bandera, he could also be described as not always having been a fascist because he spent 1941–1944 in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Bandera’s two brothers, Vasyl and Aleksandr, were incarcerated in Auschwitz where they were murdered in 1941. President Poroshenko never cited Bandera, nor ever offered to pay for the re-burial of Bandera in Ukraine. Ilyin was re-buried in Russia, while Bandera remains buried in Germany.

One can only find a ‘crisis’ in Russian nationalism (Horvath 2015) or believe that Putin ‘lost’ nationalist support (Kolstø 2016; Hale 2016) by ignoring unanimous support by Russian politicians and nationalist parties for Tsarist Russian and White Russian émigré nationalist (imperialist) and fascist views, discourse, and policies towards Ukraine and Ukrainians. Russian nationalism (imperialism) might possibly be a force for good in Russia (Tuminez 1997; Laruelle 2017a), but it has shown itself to be an evil force in underpinning Russian military aggression against Ukraine and denying the existence of Ukrainians.

Academic Orientalism and Ukrainian Nationalism

Orientalism portrayed as beneficial and generous the imperialism of colonial powers and condemned the liberating nationalism of those peoples it occupied or controlled. In scholarly studies of the Russian-Ukrainian crisis, the downplaying of nationalism (imperialism) in Russia takes place at the same time as an exaggeration of the influence and terrible evils of ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ (for an example see Amar 2019 and Kuzio 2019b).

Over the last three centuries, Ukrainians seeking a future for their country outside the Tsarist empire, USSR, and Russian World have been castigated with different names —‘Mazepinists’ (followers of Hetman Mazepa, who allied Cossack Ukraine with Sweden and were defeated by Russia in 1709), ‘Petlurites’ (followers of Symon Petlura, who commanded the army of the 1917–1921 Ukrainian People’s Republic), ‘Banderites’ (followers of OUN leader Bandera in the 1940s and 1950s), ‘traitors,’ ‘agents of Western imperialism,’ and ‘fascists’ – during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Kuzio 2017c, 85–117). A Soviet document from 30 August 1990 signed by the KGB Chairman and Minister of Interior provided instructions on how to foment ‘anti-nationalist’ propaganda to discredit the democratic opposition (Chraibi 2020). The then-KGB’s ‘anti-nationalist’ rhetoric is the same as that which continues to be used in Putin’s Russia.

The Soviet definition of ‘nationalism’ is applied to all Ukrainians who seek a destiny for their country outside the Russian World (Sakwa 2015, 2017a; Matveeva 2018; Cohen 2019). In the USSR, the term ‘bourgeois nationalist’ was applied to Ukrainians holding national communist, liberal, or nationalistic views. Soviet Communist Party of Ukraine First Secretary Petro Shelest, a national communist, was deposed in 1971 after being accused of ‘nationalist deviationism.’ Sakwa (2015, 257) claims that ‘radicalized Ukrainian nationalist elites’ were in control of the Ukrainian parliament. Hahn’s (2018, 290) claim of ‘nationalists, ultranationalists, and neo-fascist parties’ winning 44.6% of the vote in the 2014 elections can only be made by assigning the ‘nationalist’ label to all Ukrainian parliamentary political forces who were not pro-Russian.

Criticism of ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ is an outgrowth of the Western histories of ‘Russia,’ as discussed in chapter 1. Whereas the vitriolic language is lifted by Putinversteher scholars from Russian information warfare to describe the ‘grandchildren of those whose slaughtered Poles, Jews, and communists during the Nazi invasion and occupation’ (Hahn 2018, 122, 129, 166, 218, 228, 246, 285, 288, 290, 293, 295).

A majority of Western scholars believe that nationalism did not dominate the Euromaidan, and in post-Euromaidan Ukraine, nationalism is civic and inclusive (Clem 2014, 231; Kulyk 2014, 2016; Onuch and Hale 2018; Pop-Eleches and Robertson 2018; Kaihko 2018; Bureiko and Moga 2019). Civic patriotism is evident in a high proportion of Ukrainians holding negative views of Russian leaders, but not of the Russian people. Volodymyr Kulyk (2014, 120–121) writes about ‘the deeply inclusive nature of modern Ukrainian anti-imperial nationalism, the most obvious proof of which is the support it enjoys among Ukrainian Jews or even among Jews who have preserved their ties to the country since leaving Ukraine.’ Ukrainian civic identity was found in Crimea, where some of those opposed to Russia’s annexation were ethnic Russians (Nedozhogina 2019, 1086).

Ukrainian attitudes to Russian citizens and Russian leaders exhibit patriotism, not ethnic nationalism. Between 70–80% of Ukrainians hold negative views of Russian leaders, while only 20–25% hold negative views of Russian citizens (Kermch 2017). If Ukraine were so dominated by extreme nationalism, as Putinversteher scholars claim, then the country’s far right would be winning elections, and a majority of Ukrainians would hold negative ethnic nationalist views of Russian citizens.

Stalin and Putin’s Obsession with Ukraine

The Tsarist Russian Empire sought to block and repress the re-emergence of Ukrainian national identity. The Ukrainian and Belarusian languages were banned in the Tsarist Russian Empire (Saunders 1995a, 1995b). ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ was viewed as a threat to forging an ‘All-Russian People’ based on the three eastern Slavs and undermined Russian foundational myths to ownership of Kyiv Rus (Kuzio 2005). Tsarist Russian policies were ‘an all-out attack on the Ukrainophile movement and its current and potential members’ (Plokhy 2017, 146). Tsarist Russia denied the existence of the Ukrainian language and claimed there had never been a Ukrainian state, that Ukrainians had no history and that they were ‘Russians.’ Contemporary Russian information warfare propagates the same claims.

In July 1863, Minister of Interior Petr Valuev prohibited public education and religious texts in the Ukrainian language. Of the 33 Ukrainian-language publications that existed in 1863, only one survived. By the early 1870s, the system was cracking, and 32 Ukrainian-language publications re-appeared. In May 1876, the ‘liberal’ Tsar Aleksandr II issued the Ems Edict which was far more severe and ‘was intended to arrest the development of Ukrainian literature at all levels’ (Plokhy 2017, 145). The scale of Tsarist repression of the Ukrainian language was not seen in the USSR; even during the dark days of Stalinist repression, where the Ukrainian language was recognised and used in official publications. In the Tsarist Empire, the restrictions on the Ukrainian language:

Banned the import of all Ukrainian-language publications;

Banned the printing of religious and grammar books in Ukrainian;

Banned the publishing of books for ‘common people’ and intellectual elites;

Removed Ukrainian-language publications from libraries;

Banned theatre performances, songs, poetry and readings in Ukrainian;

Politically repressed Ukrainophile intellectuals.

Tsarist Russian policies backfired by assisting in turning ‘Little Russians’ into Ukrainians and, in Austrian-ruled Galicia, these policies helped to defeat the Russophile movement. The institutionalisation of the Ukrainophile movement in Galicia gave it the means to provide assistance (such as education and publications) to Ukrainophiles in the Tsarist Empire. Ukrainian historian Hrushevskyy was forced to work in Galicia, where he was chair of Ukrainian history at Lviv University and a leading member of the Shevchenko Scientific Society and National Democratic Party. In1898, he began publishing his 10-volume History of Ukraine-Rus with the final volume published in 1937. Ukrainophile activities in Galicia could only be transferred to Ukraine after the 1905 Russian Revolution. In 1917, as a member of the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries, Hrushevskyy became president of the left-wing Ukrainian People’s Republic (UNR). In 1924, he moved to the Ukrainian SSR during the Soviet policy of Ukrainianisation and died in suspicious circumstances in 1934, a year after the Holodomor.

Tsarist obsession with Ukraine was replicated in Stalin’s USSR and Putin’s Russia. Anne Applebaum (2017, 149, 155, 159) discusses the origins of (Soviet secret police) Chekist Ukrainophobia in the early 1930s during the Holodomor and mass arrest of Ukrainian national communists, educators, and cultural elites, which took place amid a frenzied search for ‘Petlurite counter-revolutionaries’ allied to external enemies of the Soviet Union. Stalin and Putin both raised and continue to raise fears of ‘losing’ Ukraine. Paranoia about Ukrainian nationalism ‘was taught to every successive generation of secret policemen, from the OGPU to the NKVD to the KGB, as well as every successive generation of party leader. Perhaps it even helped mould the thinking of post-Soviet elites, long after the USSR ceased to exist’ (Applebaum 2017, 161). Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev talked of Stalin’s plans to deport all Ukrainians in his famous speech in 1956. This did not go ahead because, Khrushchev told the congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, ‘there were too many of them and there was no place to which to deport them’ (Medvedev and Medvedev 1976, 58).

Mikhail Zygar (2016) reveals that Putin has always been obsessed and frustrated with Ukraine. Zygar (2016, 85) writes that Putin was obsessed with Ukraine from the first day of his presidency saying, ‘We must do something, or we’ll lose it’ (Zygar (2016, 258). When somebody mentions Ukraine in front of Putin, ‘he flies into a fury; the words at the end of his sentences are replaced by Russian expletives. For him, everything the Ukrainian government does is a crime’ (Zygar 2016, 4).

His obsession with Ukraine is because Putin views the Russian World as unifying the three eastern Slavs that allegedly belong to a common and ‘fraternal’ Slavic and Russian Orthodox ‘civilisation’ stretching from ‘Kievan Russia’ (Kyiv Rus) to the present day. Putin’s (2014a) speech to the State Duma and Federation Council welcoming Crimea’s accession to the Russian Federation elaborated the myth of ‘Russian’ civilisation beginning in Kyiv. Putin (2014a) believes:

Everything in Crimea speaks of our shared history and pride. This the location of ancient Khersones, where Prince Vladimir was baptised. His spiritual feat of adopting Orthodoxy predetermined the overall basis of the culture, civilisation and human values that unite the peoples of Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The graves of Russian soldiers whose bravery brought Crimea into the Russian empire are also in Crimea. This is also Sevastopol – a legendary city with an outstanding history, a fortress that serves as the birthplace of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Crimea is Balaklava and Kerch, Malakhov Kurgan and Sapun Ridge. Each one of these places is dear to our hearts, symbolising Russian military glory and outstanding valour (on the Russian myth of Sevastopol see Plokhy 2000).

Although many Western scholars are unable to find it, Putin (2008, 2014a, 2014b, 2015a, 2015b, 2017, 2019, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) has never hidden his nationalistic (imperialistic) views on Ukraine and Ukrainians. Putin (2014a) legitimised the annexation of Crimea and made territorial claims towards ‘New Russia.’ ‘After the revolution, the Bolsheviks, for a number of reasons – may God judge them – added large sections of the historical South of Russia to the Republic of Ukraine. This was done with no consideration for the ethnic make-up of the population, and today these areas form the southeast of Ukraine. Then, in 1954, a decision was made to transfer Crimean Region to Ukraine, along with Sevastopol, despite the fact that it was a federal city.’ Putin (2014a) believes that ‘this decision was treated as a formality of sorts because the territory was transferred within the boundaries of a single state. Back then, it was impossible to imagine that Ukraine and Russia may split up and become two separate states.’

Russian Nationalist (Imperialist) Imagining of Ukraine and Ukrainians

Russia’s long-term inability to come to terms with an independent Ukraine and Ukrainians as a separate people became patently obvious when Putin’s regime rehabilitated Tsarist Russian and White émigré views of Ukraine and Ukrainians (see Wolkonsky 1920; Bregy and Obolensky 1940). Igor Torbakov (2020) traces the continued influence of Tsarist ‘liberal’ and White movement supporter Struve’s view of what constitutes an ‘All-Russian People’ to contemporary Russian leaders.

In the USSR, there was a Ukrainian lobby in Moscow, while under Putin there is no such thing (Zygar 2016, 87). In the USSR, Soviet nationality policy defined Ukrainians and Russians as close, but nevertheless separate peoples; this no longer remains the case in Putin’s Russia. In the USSR, Ukraine and the Ukrainian language ‘always had robust defenders at the very top. Under Putin, however, the idea of Ukrainian national statehood was discouraged’ (Zygar 2016, 87) and the Ukrainian language is disparaged as a Russian dialect that was artificially made into a language in the USSR.

Rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian and White émigré views are to be found in Russian television programmes, where humour is used to mock Ukraine and Ukrainians in a manner ‘typical in colonizer-colonized relationships’ (Minchenia, Tornquist-Plewa and Yurchuk 2018, 225). D’Anieri (2019, 25). Russia and Russians are cast as superior, modern, and advanced, while Ukraine and Ukrainians are imagined as backward, uneducated, ‘or at least unsophisticated, lazy, unreliable, cunning, and prone to thievery.’ These kinds of Russian attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians ‘are widely shared across the Russian elite and populace’ (Minchenia, Tornquist-Plewa and Yurchuk 2018, 25; see Gretskiy 2020, 21).

Tsarist Russian and White émigré nationalism (imperialism) viewed Ukraine as ‘Little Russia’ and Ukrainians as one of three branches of the ‘All-Russian People.’ Contemporary Russian leaders agree. Surkov (2020), Putin’s senior adviser and architect of Russian policies towards Ukraine between 2014–2020, has said, ‘There is no Ukraine. There is Ukrainian-ness.’ ‘That is, it is a specific disorder of the mind, sudden passion for ethnography, taken to its extremes’ (Surkov 2020). Surkov (2020) believes that Ukraine is ‘a muddle instead of a state… there is no nation.’

Russian nationalist (imperialist) views of Ukraine crystalised during the decade before the 2014 crisis. During the 2004 presidential elections, tens of Russian political technologists operated in Ukraine working for Yanukovych’s election campaign (Kuzio 2010). They produced a number of election posters designed to scare Russian speakers about the possible electoral victory of ‘fascist’ Yushchenko, whom they claimed was married to Kateryna Chumachenko, a ‘CIA agent’ (because she had worked at one time in the US White House), and who allegedly grew up in the ‘Ukrainian nationalist’ diaspora. In fact, neither of the Yushchenkos is western Ukrainian: Viktor Yushchenko’s family is from Sumy oblast in northeastern Ukraine and Kateryna Yushchenko’s father is from Kharkiv oblast (he was one of a few survivors of the Holodomor in his family) and her mother is from Kyiv oblast.

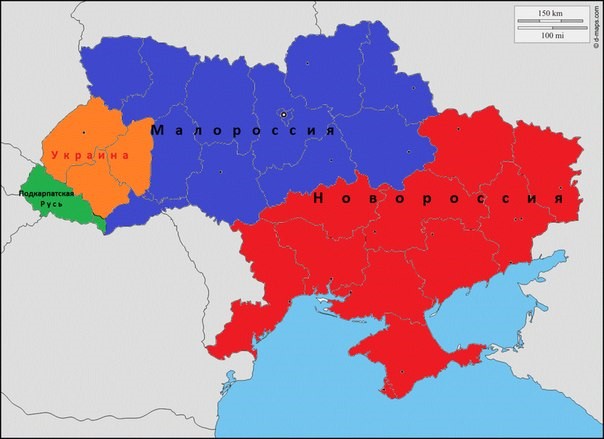

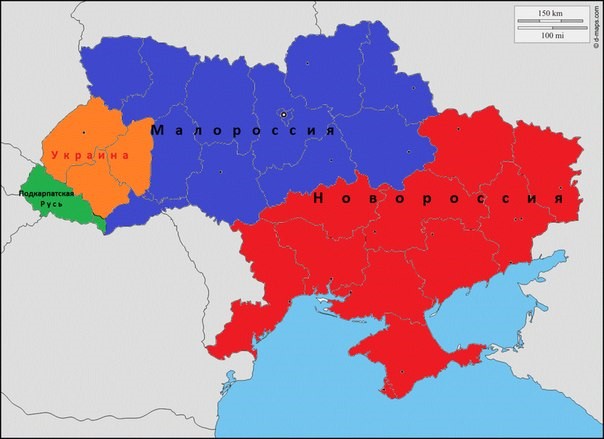

One of the 2004 election posters, reproduced below, imagines Ukraine in typical Russian nationalism (imperialism) discourse as divided into three parts. ‘Galicia’ is entitled ‘First Class’ (that is, the top of the pack), while central Ukraine (‘Little Russia’) is ‘Second Class.’ ‘New Russia’ in southeastern Ukraine was of course ‘Third Class’ (which has a striking resemblance to Putin’s ‘New Russia’) with the aim of showing Russian speakers living in this region at the bottom of the hierarchy. The poster’s captions extort Russian speakers to open their eyes at the impending threat to themselves from a ‘nationalist’ Yushchenko victory, which would lead to the domination of Russian-speaking Ukrainians by Galicia. Russian leaders and Western Putinversteher scholars believe that Galician ‘nationalism’ has ruled Ukraine since the Euromaidan.

4.1. Poster Prepared by Russian Political Technologists for Viktor Yanukovych’s 2004 Election Campaign

Text: Yes! This is how THEIR Ukraine looks. Ukrainians, open your eyes!

Note: During Ukraine’s 2004 presidential elections, Russian political technologists led by Vladimir Granovsky aimed to inflame regional divisions in Ukraine.

Source: The author obtained a copy of this poster when he was an election observer in Ukraine’s 2004 elections for the National Democratic Institute. It remains in his position and the image is a scan of this poster.

The map of Ukraine in the above 2004 election poster is remarkably similar to the traditional Russian nationalist imagining of Ukraine below:

4.2. Map of Russian Nationalist (Imperialist) Imagining of Ukraine

Note: How Russian nationalists (imperialists) have historically imagined Ukrainian territory, a viewpoint which became rehabilitated under Putin and official policy in 2014 and since. From right to left: ‘New Russia’ (southeastern Ukraine in red), ‘Little Russia’ (central Ukraine in blue), ‘Ukraine’ (Galicia in orange), ‘Sub-Carpathian Rus’ (green). Source: This map is from the author’s archives and was given to the author by a Ukrainian historian from Donetsk who is an internally displaced person living in Kyiv.

Historically and in the contemporary era, Russian nationalists (imperialists) have believed that Ukraine is composed of Crimea, ‘New Russia,’ Ukraine (‘Little Russia’), and ‘Galicia’ (western Ukraine). Crimea has always been ‘Russian,’ and its fate was decided in 2014. Western Ukraine lived for long periods outside Russian control, is Russophobic, and does not belong inside the Russian World. Russian nationalists (imperialists) believe that ‘Galicia’ should go its own way, while the rest of the country becomes part of or aligns with Russia. Russian nationalist (imperialist) Girkin supports Russia (which he conflates with the USSR) returning to its 1939 borders; that is, without western Ukraine (Bidder 2015).

In some Russian nationalist (imperialist) maps of Ukraine, Trans-Carpathia (in the above map ‘Sub-Carpathian Rus’) is separated from ‘Galicia’ based on the claim that ‘Carpatho-Russians’ live in this territory. The Trans-Carpathian region experienced a different and repressive history under Hungary to that which Galicia experienced under the more liberal Austrian part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Prior to World War I, there were three competing identities in Trans-Carpathia – ‘Russian’ (i.e. eastern Slavic), which sought union with Russia, Ukrainian, which wanted to join Ukraine in an independent state, and Rusyns, which considered itself a fourth eastern Slavic people. By World War II, only the latter two identities remained. Ukrainianisation took place in the USSR, and today the majority of the eastern Slavic population of Trans-Carpathia holds a Ukrainian identity. A Rusyn revival has taken place since the late 1980s. But ‘Russian’ identity has not existed in Trans-Carpathia for nearly a century.

The remaining territories of ‘New Russia’/Prichernomorie and Ukraine on both banks of the Dnipro river (‘Little Russia’) are viewed by Russian nationalists (imperialists) as ‘Russian’ regions with pro-Russian identities that belong to eastern Slavic Orthodox civilisation and are therefore part of the Russian World. Sakwa (2015) has little understanding of the concept of ‘Little Russia.’ Volodymyr Kravchenko (2016), a historian from Kharkiv, points out that Little Russianism does not contradict modern Ukrainian identity, but in fact ‘the two are partially intertwined and interdependent.’

The ‘natural’ union of ‘Ukraine’ and Russia has been blocked by western Ukrainian ‘nationalists,’ who came to power during the ‘illegal Euromaidan putsch’ and are in cahoots with Ukrainian oligarchs and the West. The West’s goal is to prevent the formation of a powerful Russian-Ukrainian union. Putin (2020b) has said that Russia could regain its status as ‘a global rival’ to western powers by ‘integration’ with Ukraine. ‘Some like dividing Ukraine and Russia. They believe it’s a very important goal,’ Putin (2020b) has complained, ‘Since any integration of Russia and Ukraine, along with their capacities and competitive advantages, would spell the emergence of a rival – a global rival for both Europe and the world.’

Contemporary Russian Nationalist (Imperialist) Imagining of Ukraine and Ukrainians

It is a major omission that the factors behind why Moscow is so obsessed with Ukraine are not analysed in the numerous publications on Russian information warfare. This is surprising in view of the great deal of attention that Russian information warfare devotes to Ukraine and Ukrainians.

Of the 8,223 disinformation cases that the EU database has collected since January 2015, 3,329 (40%) are on Ukraine and Ukrainians. This figure is higher than the 2,825 disinformation cases collected for the entire EU, which contains 27 countries. The EU’s Disinformation Review notes, ‘Ukraine has a special place within the disinformation (un)reality,’ and ‘Ukraine is by far the most misrepresented country in the Russian media. A Ukrainian study collected nearly 400 pages of examples of Russian disinformation on Ukraine and Ukrainians (Zolotukhin 2018).

During the Euromaidan and since, Russia’s information warfare has gone into overdrive when covering Ukraine. ‘Almost five years into the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, the Kremlin’s use of the information weapon against Ukraine has not decreased; Ukraine still stands out as the most misrepresented country in pro-Kremlin media.’ This coverage can only be explained by Moscow’s Jekyll-and-Hyde view of Ukraine as including people hostile to Russia and, at the same time, ‘good’ Ukrainians who believe that they and Russians are ‘one people.’ How can the annexation of Crimea be justified as ‘returning’ to Russia if Ukraine does not exist and Russians and Ukrainians are one people? While denigrating Ukraine at a level that would make Soviet Communist Party ideologues blush, Russian leaders continue to claim that they hold warm feelings towards Ukrainians, who are the closest people to them (Putin 2015b). With the Donbas War in full swing, the Russian Information Agency,Novosti, asked on 13 September 2014, if Ukrainians were now ‘lost brothers’ or a ‘Nazi people.’ Russia’s propaganda barrage has led to Russians viewing Ukraine as second to the US in being hostile to Russia.

The roots of Russia’s information warfare against Ukraine and Ukrainians lie in Tsarist Russian and White émigré nationalism (imperialism), Soviet propaganda, and more recent inventions. Many of the key themes on Ukraine and Ukrainians used by Putinversteher scholars are simply lifted from Kremlin’s talking points (compare them with Lavrov 2014).

‘Operation Infektion,’ launched in February 2014 and continued through the present day, has targeted nine themes with the greatest focus on ‘Ukraine as a failed state or unreliable partner’ (Nimmo, Francois, Eib, Ronzaud, Ferreira, Hernon, and Kostelancik 2020). Zolotukhin (2018) presents ten themes in Russian information warfare towards Ukraine and Ukrainians:

Ties to ISIS;

War crimes committed in the Donbas and disinterest in the Minsk peace process;

Ukrainians behind the downing of Flight MH17;

Ukraine as a NATO forward base and puppet state of the West;

EU integration as not bringing any benefits to Ukraine, which lacks the capacity to undertake reforms;

Crimea is Russian;

Western military assistance to Ukraine drives Ukrainian aggressive nationalism;

Russian fabrications on the rulings of international courts;

Ukraine as a failed state; and

Russia as a ‘schizophrenic occupier.’

The following are this author’s ten narratives of Russian information warfare towards Ukraine and Ukrainians, followed by a short description of each:

Ukraine is an artificial country and bankrupt state;

Ukrainians are not a separate people to Russians and Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people;’

The Ukrainian language is artificial and a dialect of Russian;

The Ukrainian nation was created as an Austrian conspiracy to divide the ‘All-Russian People;’

Ukraine is a puppet state controlled by the West;

Ukrainians are belittled, ridiculed, and dehumanised;

Ukraine’s reforms and European integration will fail;

Ukraine is run by ‘fascists’ and ‘Nazi’s;’

Anti-Zionism (Soviet camouflaged anti-Semitism) is used to attack Jewish-Ukrainian oligarchs; and

Distracting attention from accusations made against Russia.

First, Ukraine is an artificial country and a failed, bankrupt state. Putin (2008) raised this in his 2008 speech to the NATO-Russia Council at the Bucharest NATO summit. Ukraine as a failed state is one of the most common themes in Russian information warfare and appears in many different guises (Zolotukhin 2018, 302–358). Political collapse in 2014 required Russian intervention, Ukrainian authorities are incapable of dealing with their problems, Ukraine is not a real state and will not survive without trade with Russia, western neighbours put forward territorial claims on western Ukraine, while the east is naturally aligned with Russia, and Ukraine was artificially created with ‘Russian’ lands. Ukraine is a land of perennial instability and revolution where extremists run amok, Russian speakers are persecuted, and pro-Russian politicians and media are repressed or closed down.

Second, Russians and Ukrainians are ‘one people’ with a single language, culture, and common history (Zolotukhin 2018, 67–85). Russian information warfare and western histories of ‘Russia’ portray Ukraine as a place without its own history and identity. Ukrainians are a ‘brotherly nation’ who are ‘part of the Russian people,’ and reunification, Putin (2017) told the Valdai Club, will inevitably take place. ‘One people inhabits Ukraine and the Russian Federation, for the time being, divided (by the border),’ Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolai Petrushev (2016) has said.

Third, the Ukrainian language does not exist and what is spoken in Ukraine are dialects of Russian. Although the USSR promoted Russification, it nevertheless recognised the existence of the Ukrainian language. The Russian information agency Rex published an article claiming that the ‘Ukrainian language is a weapon in the hybrid war’ because the Ukrainian language is ‘artificial.’ The Ukrainian language is a form of hybrid, ‘brain programming’ political technology (Yermolenko 2019).

Fourth, the Ukrainian nation is a conspiracy directed against Russia. This idea was first promoted by Russian nationalists (imperialists) in the late-nineteenth century when the Tsarist Russian and Austrian-Hungarian empires competed over control of western Ukraine. This myth is closely tied to that of an artificial Ukrainian state as a puppet of the West seeking to divide the ‘All-Russian People.’

Tsarist authorities and Russian political parties have claimed that the Ukrainian people do not exist and are a mere fiction dreamt up by Austrians and other foreign powers to divide the ‘All-Russian People’ (Weeks, 1996). Incredibly, Putin (2020b) has revived this late-nineteenth century Tsarist nationalist (imperialist) views of Austrians creating a fictitious Ukrainian nation: ‘The Ukrainian factor was specifically played out on the eve of World War I by the Austrian special service. Why? This is well-known – to divide and rule (the Russian people).’

White émigrés perpetuated this Russian chauvinistic myth, which has been rehabilitated in Putin’s Russia. White émigrés Prince Alexandre Wolkonsky (1920), Pierre Bregy, and Prince Serge Obolensky (1940) would feel at home in Putin’s Russia. One hundred White émigré aristocrats living in western Europe signed an open letter of support for Russia during the 2014 crisis (Laruelle 2020b, 353–354).

These nineteenth century and pre-World War II views of Ukraine and Ukrainians were espoused by Russian nationalists (imperialists) and fascists, and were incorporated into the discourse of Russian leaders. Four years prior to Putin talking about an Austrian conspiracy lying behind a separate Ukrainian nation, the leader of the Russian Imperial Movement, Stanislav Vorobyev (2020), made the same statement. Vorobyev (2020) and Putin (2015a, 2015b) view ‘Russians’ as the most divided people in the world and believe that Ukrainians are illegally occupying ‘Russian’ lands.

Girkin, also a member of the Russian Imperial Movement, believes that the ‘real separatists’ are ‘the ones in Kyiv, because they want to split Ukraine off from Moscow’ (Bidder 2015). Girkin’s brand of ‘imperial nationalism’ defines ‘Russians’ as encompassing three eastern Slavs and all Russian speakers (Plokhy 2017, 342). Vorobyev (2020) has stressed that Ukrainians ‘are not an ethnos’ but a ‘socio-political group of separatists’ who, after the USSR disintegrated, ‘obtained Russian historic lands of the Russian people (as in 4.2. Map): Malorossiya (Little Russia), Slobozhanshchyna (Kharkiv region), Hetmanshchyna (central Ukraine), ‘New Russia,’ and Crimea, and as a result of this crime they have obtained lands that never belonged to them.’ As in Western histories of ‘Russia,’ Ukrainians are again squatters on primordial ‘Russian lands.’

Contemporary Russian leaders have revived the Tsarist Russian nationalist (imperialist) concept of the three branches of the ‘All-Russian People’ with Ukrainians as ‘Little Russians.’ Ukrainians breaking away from triyedinyy russkij narod are the separatists – not Russian proxies in the Donbas. A Russian mercenary fighting for Russian proxies was asked if he supported independence for the Donbas, to which he replied, ‘Independence from whom?’ He had travelled to the Donbas to ‘protect the Russian people’ (understood as the triyedinyy russkij narod) and stand up for ‘this brotherly people’ (Goryanov and Ivshina 2015).

Putin and the Russian Imperial Movement agree that Ukrainians do not exist. Similar to Suslov (2020), Vorobyev (2020) has said, ‘Ukrainians are some socio-political group who do not have any ethnos. They are just a socio-political group that appeared at the end of the nineteenth century by means of manipulation of the occupying Austro-Hungarian administration, which occupied Galicia.’ There is no difference between the nationalist (imperialist) attitudes of President Putin towards Ukraine and Ukrainians and those of Vorobyev’s fascist Russian Imperial Movement. This explains why national Bolsheviks, anti-Semites, and Russian chauvinists support Putin on Ukraine (Dugin 2014; Glazyev 2019; Surkov 2020).

Fifth, Russia’s civilisation is unique and in competition with the West, whose ‘fifth column’ in Eurasia and the Russian World is the ‘puppet’ state of Ukraine led by Galician nationalists who came to power in the Euromaidan (Laruelle 2016c). Russia is not fighting Ukrainians who belong to the ‘All-Russian People’ living in ‘New Russia’ and ‘Ukraine,’ and who are being prevented from being part of the Russian World. Ukraine is always portrayed as a country without real sovereignty, which only exists because it is propped up by the West. Similar to Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns, Ukrainian ‘nationalists’ are depicted as the West’s puppets and since 2014 have been doing the West’s bidding by dividing the ‘All-Russian People.’ Russian information warfare describes Poroshenko and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy as ‘puppets’ of Ukrainian nationalists and the West.

Similarly derogatory descriptions are made by Cohen (2019, 145), who describes US Vice President Joe Biden as Ukraine’s ‘pro-consul overseeing the increasingly colonized Kyiv.’ President Poroshenko was not a Ukrainian leader, but ‘a compliant representative of domestic and foreign political forces,’ who ‘resembles a pro-consul of a faraway great power’ running a ‘failed state’ (Cohen 2019, 36).

Cohen (2019) and Glazyev (2019), both with a history of support for left-wing politics, agree about Ukraine as a Western puppet state. Glazyev (2019) writes: ‘By itself, the election of a new president of Ukraine does not change the situation,’ because it is ‘obvious that in the top three candidates who won the majority of votes in the first round of the presidential “election,” there was not a single candidate who did not swear allegiance to the American occupation authorities.’

Sixth, Russian media and information warfare routinely dehumanise Ukraine and Ukrainians by belittling the idea that they can exist without external support, whether that support is Russian or western. One example of this idea is found in the mocking and ridiculing of Ukraine on Russian television as possessing a navy during the November 2018 Russian-Ukrainian naval confrontation in the Azov Sea.

Seventh, spreading disillusionment in Ukraine’s reforms and European integration is an outgrowth of previous themes. Ukraine and Ukrainians, because of their artificiality, are unable to introduce reforms and fight corruption, and therefore the goal of joining the European Union will end in failure. Ukraine is plagued by corruption and ruled by oligarchs. To hammer this point home, a final point is made that nobody is waiting for Ukraine in Brussels and that eventually Kyiv will understand this and return to Russia’s bosom.

One important reason for propagating this theme is that the potential threat of the success of Ukrainian reforms and their destabilising influence on Putin’s authoritarian system. Ukraine is a hub for anti-Putin opposition activities and exiled journalists.

Eighth, drawing on Soviet ideological campaigns against ‘Nazi collaborators’ in the Ukrainian diaspora, Ukraine is depicted as a country ruled by (Galician) ‘Nazis’ and ‘fascists’ – even after Zelenskyy, who is of Jewish-Ukrainian descent, was elected Ukrainian president. Soviet propaganda and ideological campaigns attacked dissidents and the nationalist opposition as ‘bourgeois nationalists,’ who were in cahoots with Nazis in the Ukrainian diaspora and in the pay of western and Israeli secret services. Today, a ‘Ukrainian nationalist’ in Moscow’s eyes is anybody who supported the Euromaidan and Ukraine’s future outside the Russian World.

With President Zelenskyy continuing his predecessor’s support for the goal of Ukraine joining the EU and NATO, Russia has also begun criticising him as a ‘nationalist.’ Director of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) and Chairman of the Russian Historical Society, Sergei Naryshkin (2020), commenting on the statements of the Ukrainian president during his visit to Poland said, ‘It is clear that Mr. Zelenskyy is more and more immersed in the ideas of Ukrainian nationalism.’ With Glazyev’s (2019) background in the national-Bolshevik Rodina party, it is unsurprising that he reacted to Zelenskyy’s election with an anti-Semitic diatribe (on anti-Zionism and anti-Semitism, see Kuzio 2017c, 118–140).

A common theme in Russian information warfare and diplomacy is the claim that, with ‘nationalists’ and ‘Nazis’ ruling Ukraine, there is an existentialist threat to Russian speakers. Putin (2019) refuses to countenance the return of Ukrainian control over the Russian-Ukrainian joint border because of the alleged threat of a new ‘Srebrenica-style’ genocide of Russian speakers similar to that perpetrated by Serbian forces against Muslim Bosnians in July 1995.

With Russian nationalists (imperialists), convinced that ‘New Russia’ is inhabited by ‘Russians,’ they are unable to fathom the very concept of Russian-speaking Ukrainian patriotism. Mocking Russia’s obsession with searching for ‘fascists’ in Ukraine, Jewish-Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoyskyy began wearing tee-shirts emblazoned with Zhydo-Banderivets (Jew-Banderite), a sarcastic reference to his status as an alleged Jewish supporter of Ukrainian nationalist leader Bandera.

Ninth, Soviet anti-Zionism, a camouflaged form of anti-Semitism, has been revived in Russian information warfare against Ukraine and by Russian proxies in the DNR and LNR. Glazyev (2019) linked Zelenskyy’s election to the ‘general inclination of the Trump administration towards the extreme right-wing forces in Israel.’ Glazyev does not attempt to hide his anti-Semitism, bizarrely claiming that the Trump administration will ‘set new tasks for the renewed Kyiv regime. I do not exclude, for example, the possibility of a massive relocation to the lands of Southeast Ukraine “cleansed” from the Russian population of the inhabitants of the Promised Land who were tired of permanent war in the Middle East, just as Christians fleeing from Islamised Europe.’ This anti-Semitic claim was made by one of Putin’s senior advisers on Ukraine, who together with Medvedchuk was a joint architect of Russian strategy that pushed Ukraine to crisis in 2013–2014.

Ukraine’s oligarchs, such as Jewish-Ukrainian Kolomoyskyy, who took a decisive stance against Russia as governor of Dnipropetrovsk in 2014, are pillorised as being in bed with Ukrainian nationalists. Ukraine is being colonised by the EU, US, and the West as part of a liberal, elite conspiracy that promotes globalisation to destroy the sovereignty of nation-states. Globalisation, with George Soros as a favourite target, is synonymous with a world-wide Jewish conspiracy.

The tenth theme has its origins in the USSR, which covered up crimes it had committed against its own people and those undertaken by its security forces and assassins abroad. The 1933 Holodomor, for example, was denied by the USSR until 1990 (Applebaum 2017). Those who wrote about the Holodomor in the Ukrainian diaspora and well-known historians, such as Robert Conquest, were castigated as anti-Soviet ‘Cold War warriors’ (see Tottle 1987). Tarik Amar (2019; see Kuzio 2019b) continues this genre in devoting 20 of his 24-page review of Applebaum (2017) not to the Holodomor, the subject of her book, but to the evils of ‘Ukrainian nationalism’ (see Kuzio 2019b).

The rehabilitation of Stalin is accompanied by the denial of Stalinist crimes against Poles, such as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and 1940 Katyn massacres, the Holodomor, and the 1939 occupation of the three Baltic states. Sputnik International, an important weapon of Russian disinformation abroad, published the ‘Holodomor Hoax: Anatomy of a Lie Invented by the West’s Propaganda Machine’ (Blinova 2015) nearly three decades after the same arguments were used by Canadian communist Douglas Tottle (1987). In 2015, books by Polish Jewish scholar and lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who developed the concept of genocide after World War II and wrote about and testified on the Holodomor, were included in Russia’s Federal List of Extremist Materials. In August 2020, on the eve of Ukraine’s Independence Day, the monument to a little starving girl called the ‘Bitter Memory of Childhood’ outside Kyiv’s National Museum of Holodomor Genocide was vandalised in what the General Director of the museum, Olesya Stasyuk, described as an ‘inadmissible offense against the memory of an entire nation.’

Russian information warfare continues in the Soviet tradition of covering up crimes committed by the Kremlin. Blame for the shooting down of the civilian airliner MH17 is shifted away from Russia and the existence of Russian security forces in eastern Ukraine. Distraction of blame over the shooting down of MH17 has gone through 200 disinformation stories, which have been regurgitated in pseudo-academic writing (Pijl 2018).

Russia has always denied the existence of Russian forces in eastern Ukraine and, when these forces have been caught, has blamed soldiers ‘getting lost’ or ‘being on holiday.’ Nearly two-thirds of Ukrainians (65%) believe that Russian troops are in Ukraine, whereas only 27% of Russians believe this. Additionally, 72% of Ukrainians (but only 25% of Russians) believe that their two countries are at war (Poshuky Shlyakhiv Vidnovlennya Suverenitetu Ukrayiny Nad Okupovanym Donbasom: Stan Hromadskoyii Dumky Naperedodni Prezydentskykh Vyboriv 2019; Shpiker 2016).

Conclusion

This chapter has provided evidence and analysis of Russian nationalism (imperialism) and chauvinism towards Ukraine and Ukrainians. Nevertheless, nationalism (imperialism) in Putin’s Russia continues to be downplayed, marginalised, or described as temporary by Western scholars. Between the 2004 Orange Revolution and Putin’s re-election in 2012, Russian nationalism (imperialism) rehabilitated Tsarist Russian and White émigré views of Ukraine and Ukrainians into official discourse, military aggression, and information warfare. In 2007, the two branches of the Russian Orthodox Church were re-united, and the Russian World Foundation was created. Between 2008–2012, Putin evolved into viewing himself as the ‘gatherer of Russian lands,’ which include Ukraine. The most extreme example of this evolution was Putin (2020b) incorporating into official discourse the late-nineteenth century Tsarist Russian conspiracy of Austrians creating a fake Ukrainian people that had been earlier rehabilitated by Russian fascists (Vorobyev 2020).

In the same manner as western orientalism had earlier imagined in a negative manner peoples fighting for their national self-determination in their colonies, Putinversteher scholars have copied Kremlin templates about the evils of ‘Ukrainian nationalism.’ Ukraine, which has one of the lowest levels of electoral support for extreme right parties in Europe, is allegedly over-run by Nazis. At the same time, western scholars can find little or no evidence of nationalism in Russia, where it dominates domestic politics, underpins a cult of the murderous tyrant Stalin, and fuels territorial conquest and military aggression against Georgia and Ukraine. In reality, nationalism in Ukraine has become more civic since 2014.

This chapter has analysed how academic orientalism permeates the writings of western political scientists on the 2014 crisis, Russian-Ukrainian War, and Russian and Ukrainian nationalism. The next chapter takes my application of academic orientalism further by applying it to claims of a ‘civil war’ taking place in Ukraine to show that this is a false narrative that is not supported by what took place or by Ukrainians. The roots of the 2014 crisis go as far back as 1991 (D’Anieri 2019) and concern Russian intervention in Ukraine in the decade prior to the annexation of Crimea and hybrid warfare in Donbas. The next chapter provides evidence of a Russian-Ukrainian War taking place. The false narrative of a ‘civil war’ dovetail with Ukraine being portrayed as a country with acute regional divisions between Russian and Ukrainian speakers, which was captured by Galician-based ‘Ukrainian nationalists’ during the Euromaidan.

No comments:

Post a Comment