Lukas D. Herr

In April 2019, Congress cast a historic vote. For the first time, both chambers made use of the War Powers Resolution (WPR, Public Law 93-148), a resolution passed in the waning days of the Vietnam War to restore congressional authority in deciding when the nation goes to war, and directed President Trump to stop U.S. participation in the war in Yemen. Although Congress ultimately failed to override Trumps presidential veto, only one year later, Congress acted upon the WPR again. This time, Congress sought to restrict President Trump’s ability to use force against Iran and decided to ‘direct the removal of United States Armed Forces from hostilities against the Islamic Republic of Iran that have not been authorized by Congress’ (U.S. Congress 2020). Again, President Trump vetoed the resolution, stating that the resolution’s understanding of limited presidential power ‘is incorrect’, because ‘the Constitution recognizes that the president must be able to anticipate our adversaries’ next moves and take swift and decisive action in response’ (Trump 2020). Then Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden urged Congress to override President Trump’s veto, however, and to assert itself against presidential war-making. In his statement, Biden condemned President Trump’s veto and ‘his contempt for the U.S. Congress as a co-equal branch of government’ and added that, as president, he ‘will work closely with Congress on decisions to use force, not dismiss congressional legislation’ (Biden 2020).

At this point, it is worth remembering President Barack Obama, who, as presidential candidate, promised quite a similar approach to the politics of military interventions and the role of Congress. In an interview with the Boston Globe in December 2007, Obama stated that the president ‘does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation’ (Obama 2007). Nevertheless, he acted otherwise. During the military intervention in Libya 2011, Obama followed the legal interpretation of Harold H. Koh, Legal Adviser to the State Department, according to which the military intervention in Libya was consistent with the WPR and did not require congressional authorization, ‘because U.S. military operations are distinct from the kind of ‘hostilities’ contemplated by the Resolution’s 60 day termination provision’ (U.S. Department of State 2011: 25). Following this interpretation, which the New York Times called ‘legal acrobatics’, the president could unilaterally wage war against a country as long as the United States was only engaged in air strikes and expected no or few casualties, therefore strengthening the conviction that presidents possess inherent war powers independently from Congress (Pious 2007; Yoo 2005)

Although the framers of the constitution acknowledged that in the event of a sudden attack the President as ‘Commander in Chief’ had the duty to protect the mainland and the troops of the United States, the ‘President never received a general power to deploy troops whenever and wherever he thought best, and the framers did not authorize him to take the country into full-scale war or to mount an offensive attack against another nation’, according to Louis Fisher (2013: 8-9), one of the leading scholars on U.S. war powers. It was during the presidency of Richard Nixon and the final phase of the Vietnam War in 1973 that legislators realized they needed to assert themselves against a presidency which usurped more and more powers from Congress and led the country into an undeclared war.

In order to roll back what Arthur Schlesinger (2005 [1973]) has termed and what later has become widely known as the ‘Imperial Presidency’, Congress adopted the WPR against Nixon’s veto and provided itself with several procedures and legislative measures to limit presidential war-making and restore the ‘balance of power’ envisaged by the framers of the constitution. Two measures are especially important and noteworthy: first, section 5(b) of the WPR directs the president to terminate any use of U.S. armed forces in hostilities which have not been authorized or declared by Congress within sixty days, and second, section 5(c) provides Congress with the ability to direct the president to remove armed forces engaged in hostilities outside the territory of the United States by a concurrent resolution which, unlike other resolutions, does not require presidential approval. Even though this mechanism has been updated to comprise joint resolutions as well, since a Supreme Court ruling deemed legislative vetoes by concurrent resolutions unconstitutional, neither the House nor the Senate passed such legislation until April 2019, and Congress failed to fully utilize its instruments to curtail presidential power in the field of military interventions.

The question this article tries to answer is therefore straightforward: will Joe Biden, as the 46th president, follow Trump’s footsteps and toss away his promise to acknowledge Congress as a ‘co-equal branch of government’, as Obama did in Libya 2011, or will lawmakers successfully reign in the ‘Imperial Presidency’ and arrange for a new relationship between the presidency and Congress? In other words, what can we expect for the future of executive-legislative relations when it comes to the use of military force?

The Historical Record: Joe Biden and the Powers to Wage War

As president, Biden will have a congressional record unlike most other presidents before him. As one of 17 presidents, Biden served in the Senate before, where he represented Delaware from 1973 to 2009. This will make him the president with the longest time in the Senate, superseding Lyndon B. Johnson who represented Texas from 1949–1961. During his decades-long tenure as senator, Biden not only voted on the WPR in 1973, but was involved in the authorization of every major military intervention of the United States up until 2009, when Biden became vice-president of the United States. This includes the war in Afghanistan and the subsequent war in Iraq as well as several military interventions during and after the Cold War. In fact, Biden voted to authorize the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, along with the Gulf War in 1991 and the aerial warfare in Kosovo against Serbia in 1999, although this authorization did not become law because it failed to pass the House of Representatives by a vote of 213:213 in April 1999.

Besides these major authorizations, Biden was involved in many other votes regarding the use of military force, many of them limiting presidential war-making. In fact, Congress cannot only restrict the president’s power to wage war through its 1973 WPR, but through other legislative means as well. These include funding limitations as well as limitations on the scope and duration of the use of military force, or by providing the conditions under which U.S. troops can be deployed in hostilities through annual appropriation and authorization bills, which act as vehicles for restrictions through their relevance as ‘must pass’ legislations (Howell/Pevehouse 2007: 10-17, for an overview of congressional votes on the use of force abroad see this report of the Congressional Research Service).

Considering these alternative ways to limit presidential war-making, a slightly different picture of Joe Biden emerges, one in which he not only authorized presidential war-making on many instances, but also one in which he was willing to curtail it as well.

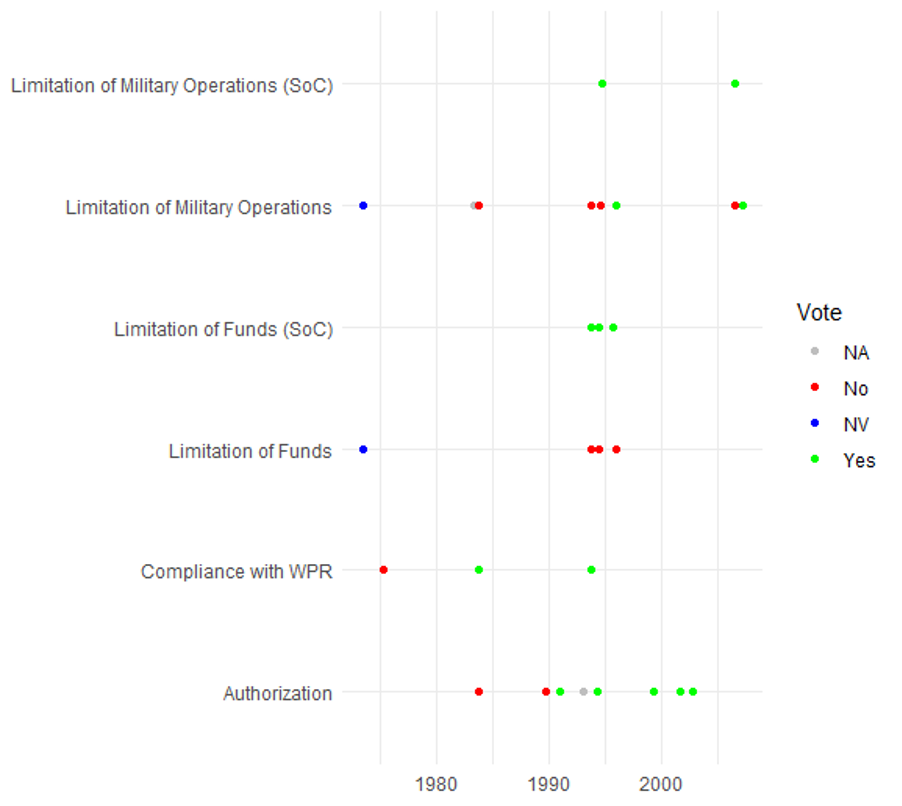

Figure 1: Congressional Votes of Joe Biden on the Use of Military Force Abroad

Note: Votes on motions to table a resolution have been inverted, in order to make them comparable with votes explicitly for limitations on presidential war powers. SoC stands for non-binding Sense of Congress resolutions. The complete list of votes can be obtained from the author.

The figure above plots Joe Biden’s authorization votes on each major instance involving the use of military force by the U.S. over time as well as the different ways Congress can limit the president’s power to wage war.[1] Three conclusions can be drawn from this depiction. First, although Biden voted to authorize almost every major use of force, there are three instances in which Biden did not authorize the use of military force: the military interventions in Lebanon 1983, in Panama 1989 and in Iraq 1991. During the intervention in Lebanon 1983, for example, Biden voted against a compromise resolution that authorized the ongoing deployment of U.S. forces in Lebanon for an additional 18 months under the WPR. Instead, he voted for two amendments which would have extended the sixty days deadline of the WPR for another sixty days and determined that hostilities according to the WPR exist, therefore forcing the president to adhere to the limitations of the WPR (both amendments did not make it into the resolution and died during the legislative process). Of course, this does not prove that Biden opposed the use of military force in Lebanon per se, but it does show that Biden was certainly aware of the broad timeline Congress would have given President Reagan through its compromise resolution.

Second, although Biden seems to have been reluctant to set binding restrictions on ongoing military operations, there are two cases where Biden voted to limit presidential war-making. In 1995 Biden voted for a resolution that would have authorized President Clinton to use armed forces to implement the Dayton Agreement in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but only for ‘approximately one year’ (U.S. Congress 1995), whereas in 2007, Biden voted for a binding timeline to withdraw American troops from Iraq, revising his decision in 2002 to authorize the Iraq War. Especially the Iraq vote is important as Biden was the Chair of the Foreign Relations Committee during the authorization vote in October 2002 and one of the key Democrats who supported the AUMF, leading to Biden’s ‘checkered history with Iraq’ (Golshan/Ward 2019).

Third, even though Biden seems to have been willing to limit presidential war-making for Republican as well as Democratic presidents – from 14 votes to restrict the president, six were under Republican and eight under Democratic presidents – Biden mostly refrained from using the power of the purse to set limitations. The figure above shows that whereas Biden was consistently willing to vote for non-binding funding limitations through Sense of Congress (SoC) resolutions, the only instance where Biden set a minor limitation through the funding of military operations occurred during the military intervention in Somalia 1993, when Biden voted to adopt an amendment that permitted the use of funds for the mission in Somalia after March 31, 1994 only, if the president sought and Congress provided specific authorization.

Admittedly, the question remains if we can infer from Senator Joe Biden’s previous voting behavior how Biden will act as a president, equipped with broad presidential (war) powers? Hendrickson (2010, 205) argues for the early Obama administration for example that Obama’s and Biden’s ‘previous views on congressional war powers are not […] the guiding constitutional principles that shape their relationship with the Congress’, because ‘as for previous presidents, assertiveness as commander in chief is an institutional pattern in the conduct of the executive branch’. Indeed, Obama accepted these institutional patterns during the Libya intervention and acted unilaterally without congressional support.

However, in 2020, two things stand in favor of Joe Biden’s promise to acknowledge Congress as a ‘co-equal branch of government’. First, Obama learned from the congressional opposition to his unilateral action in Libya that congressional support is indeed a vital asset in war-making. In 2013, Obama decided to seek congressional approval for a military strike in retaliation for a chemical weapons attack by the Syrian government, breaking with the tradition of using military force without congressional permission. Second, in an interview with Charlie Rose on PBS, Biden claimed that he strongly argued against an intervention in Libya within the administration and, as the ‘Afghanistan Papers’ revealed, was one of the ardent opponents of Obama’s decision in 2009 for a troop surge in Afghanistan. Therefore, it seems likely that Biden learned from the Libya debacle and knows about Congress’ role and influence on public support for military interventions (Howell/Pevehouse 2007; Kriner 2018).

The Other Side of the Coin: Congressional Action to Limit Presidential War Powers

That presidents usually prevail in foreign policy is not only a consequence of ‘presidential rapacity’, which, according to Biden’s legislative record, is less likely to occur during his presidency, but from ‘congressional pusillanimity’ as well, as Schlesinger (2005: x) noted in his seminal work on the ‘Imperial Presidency’. In fact, if Congress really wants to restore the constitutional balance between Congress and the presidency, lawmakers not only need to make use of their implicit instruments to control and check presidential power, such as hearings and congressional investigations that might deter the presidency from any unilateral actions, but also Congress’ real legislative powers. Besides using these powers in prospective confrontations that loom ahead for the next presidential term, such as the potential unilateral use of force against Iran which Congress recently tried to block, two main legislative mechanisms are clearly in need of improvement. First, the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF, Public Law 107-40) from 2001, which was originally adopted to authorize the war in Afghanistan after 9/11 but has lately become a catch-all legitimation for almost any use of military force, and second, the WPR itself, which has failed to effectively relocate power back from the president to Congress since its adoption in 1973.

The AUMF 2001, which was adopted by Congress only three days after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, authorized President Bush ‘to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks’ (U.S. Congress 2001), giving Bush and his successors in office a blank cheque to use force against terrorism wherever they wished. Although several resolutions tried to fix this imbalance and aimed at reasserting the role of Congress in deciding where military force should be conducted, none of these legislative measures have made it through Congress, leaving the 2001 AUMF, as well as the 2002 AUMF against Iraq, still in place.

However, two recent attempts are noteworthy. First, in 2018, Senators Bob Corker (R-TN) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) came up with a joint resolution to repeal the 2002 AUMF and replace the 2001 AUMF with an updated and more tailored authorization. According to their 2018 AUMF proposal, the president would have been authorized ‘to use all necessary and appropriate force against the Taliban, al Qaeda, and the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS)’ (U.S. Congress 2018), as well as its associated forces. During and after hearings in the Foreign Relations and the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs’ Subcommittee on Federal Spending Oversight and Emergency Management, lawmakers and experts sharply criticized the proposed AUMF, however. The new AUMF, the opponents argued, would cement the status quo and give Trump and his successors the ability to unilaterally wage war wherever they liked. Ultimately, the resolution, as well as a proposal by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR) in response to the criticism could not garner enough support to make its way onto the floor of the Senate.

During the expiring recent legislative period, a promising attempt has been made by several lawmakers in the House of Representatives, who came up with a bipartisan compromise resolution (Herr et al. 2020). The new resolution would leave the 2001 AUMF in place, but would limit its scope to ongoing hostilities and prohibit future uses of force to be justified with it. According to the bipartisan coalition, which tries to restore congressional authority, the resolution ‘is neither an attempt to repeal the authorization nor a statement on current or previous U.S. military actions’, but ‘would put constitutional guardrails on the further expansion of an almost two-decades-old authorization’ (Brown et al. 2020).

Although the proposal would leave future presidents with ample room of maneuver and even though it reaches out to a Republican controlled Senate and unifies different ideological positions on the use of military force as well, its prospects for success are dim. Even if Biden would support, or at least not obstruct, such a congressional effort, there are no signs of rising bipartisanship in the near future, which proved to be a significant condition for congressional action (Böller/Müller 2018). Furthermore, in the light of the rampant Covid pandemic and its economic consequences in the United States, updating an almost 20 years old legislation is unlikely to be on top of Congress’ political agenda.

The same fate will likely be true for an update of the 1973 WPR. The latest attempt to reform the WPR was made by Senator Kirstin Gillibrand (D-NY) and Representative Anthony Brown (D-MD), who introduced the War Powers Reform Resolution. This legislative attempt aims at amending the WPR with a new section that would limit new AUMF’s to a maximum of two years and prohibit the use of appropriated funds for the unauthorized introduction or use of United States Armed Forces into hostilities. However, the reform resolution would retain the sixty-days deadline, which allows the president to use military force for sixty days without congressional authorization. The sixty-days clock has been identified as one of the major problems of the WPR, because, according to Tess Bridgeman and Stephen Pomper, it ‘has been treated by both of the political branches as more or less free time during which the president is permitted to launch operations’ (Bridgeman/Pomper 2020). Notwithstanding the moderate changes proposed, the reform resolution has not managed to gain any legislative track since it was introduced a year ago and it remains to be seen if the new Congress will pick up on this approach.

Conclusion

This article has argued that two factors are crucial for turning back the ‘Imperial Presidency’ and for restoring Congress’ constitutional rights and duties when it comes to the use of military force. First, presidents need to truly recognize Congress as a co-equal branch of government and act accordingly, and second, Congress in general and lawmakers in particular must not only wait for presidential generosity, but confidently use their constitutional powers to establish binding limits on the president’s power to wage war. An analysis of Biden’s history as a senator as well as recent legislative measures shows that the prospects for an emancipated relationship between the Congress and the presidency might have risen a little bit.

Biden’s record as a senator indicates that he is not only aware of the problem of an ever-expanding presidency, but also of Congress’ independent powers when it comes to the use of military force. During his decades-long tenure in the Senate, Biden repeatedly voted to limit presidential war-making both through the WPR and Congress’ other legislative means to put limitations on military operations. In addition, Biden served as vice president during the Obama administration and witnessed first-hand Congress’ opposition when Obama contradicted his own promises that presidents cannot wage war without congressional approval during the military intervention in Libya 2011.

Restoring congressional status depends on repelling the 2001 and 2002 AUMF as well as reforming the 1973 WPR. Not only do the nearly two-decades old AUMF’s act as catch-all legitimations for ongoing and prospective military operations, the history of the WPR also shows its deficiencies in restoring Congress’ role in deciding if military force is being used. Even though the outlook for repelling both AUMF’s and for reforming the WPR seem to be dim, lawmakers have signaled during the last two years that they are willing to enforce their constitutional and legislative rights. It remains to be seen if sufficient Republicans and Democrats are willing to cross the aisle in the future or if the moderate bipartisanship we have seen in the last two years ends along with the presidency of Donald Trump.

Notes

[1] These include the Vietnam War 1973-1976, the use of military force in Lebanon 1982-1983, the U.S.-Invasion in Grenada 1983 and in Panama 1989-1990, the Gulf War in 1991, the uses of military force in Somalia 1992-1994, in Haiti 1993-1994, in Bosnia 1993-1995, and in Kosovo 1999, as well as the wars in Afghanistan 2001-2008 and in Iraq 2003-2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment