By PARAG KHANNA

As U.S.-China relationships further deteriorated this spring, Chinese company ByteDance, the owner of platform TikTok, appeared to respond by opening up hundreds of new jobs in its Singapore office. The move was an acceleration of a long-term trend for the $100 billion company, which has been moving to localize its products for Southeast Asian consumers, and to forge new relationships with governments and utilities, expanding its soft power — and China’s.

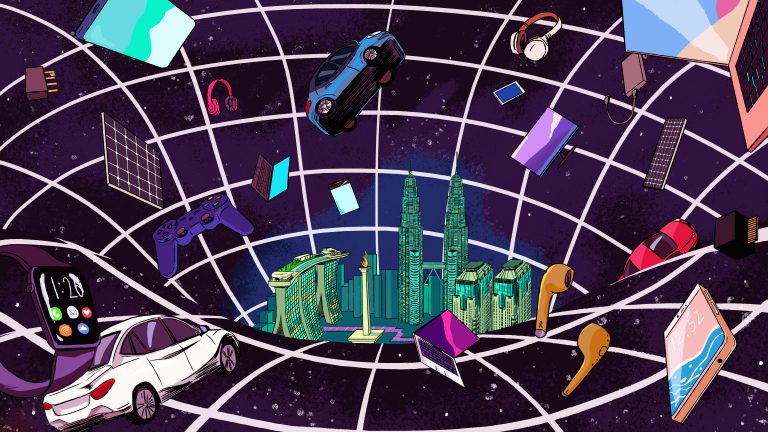

Indeed, well before the U.S.-China trade war thrust Singapore and the rest of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a catchall term for an area encompassing ten countries and 700 million people, into the spotlight, it had been experiencing an economic renaissance. As supply chains for technology shift, as Chinese and American companies compete for the huge opportunities in the region, and as governments and militaries jostle for strategic position, the region seems to be at the nexus of a great power rivalry in 2021 — and likely beyond.

But even as geopolitical rivalries beset Asia, supply chains and technology continue to flow like water, seeping across borders. Thus, the U.S.-China competition to carve up Southeast Asia into discrete spheres of influence is a scenario spoken about far more outside the region than within it. That alone is a vital reminder of the gap between perception and reality, between would-be masters of the universe and happenings on the ground. But Southeast Asia is not virgin territory: geopolitics, trade, investment, and technology are already deeply entangled across the region. The region is ground zero not for a new Cold War but rather a more sophisticated and layered diplomacy — a “multi-alignment” of sorts — in which the protagonists do not choose sides but play all sides to their own benefit.

During the Cold War, Southeast Asia was seen as a set of dominoes falling toward either Soviet or American camps. But today it is, above all, the center of the Asian megaregion. Neither China nor the U.S. is Southeast Asia’s largest investor. Japan began shifting its manufacturing supply chains out of China and into lower-cost Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, and India in the early 2010s. American and European multinationals pursued a similar strategy, recognizing the opportunities in the region’s young population and fast-growing consumer markets. A “China plus one” model took root, with “make where you sell” becoming the new norm in diversifying production.

Japan has retained its leading role as an investor, both in terms of volume and breadth. Unlike the U.S., it has joined two megatrade frameworks, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Asia-centric Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Even as Tokyo seeks to bring its high-end manufacturing back onshore by offering subsidies to Japanese companies, it is also ramping up investment across Southeast Asia, to boost exports to these high-growth markets.

Knit tightly into global supply chains, Southeast Asia’s manufacturing sector effectively wins twice from the U.S.-China trade war: American companies are shifting investment from China to reduce costs and avoid tariffs, and China will import more from Southeast Asia to substitute for the U.S. within the RCEP framework.

In the years to come, rising geopolitical tension in Asia could further bolster Southeast Asia’s tech supply chain economy. The Quad — the U.S., Australia, Japan, and India — have worked to counter Chinese territorial and maritime aggression, efforts that have since spilled over into the industrial arena, with a Resilient Supply Chain Initiative (RSCI) yanking multinational manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, electric vehicles, solar panels, semiconductors, and other high-value sectors out of China and mostly into Southeast Asia.

Given China’s geographic proximity to Southeast Asia, it is logical that Chinese lenders and contractors are trying to lead the region’s largest infrastructure projects. But digital infrastructure remains a realm of intense competition, as evidenced by U.S. attacks on Huawei, the Chinese national technology champion. While Huawei advanced its market share in 5G on the back of international standard-setting efforts, European providers, such as Ericsson and Nokia and Japan’s NTT, are gaining ground. This is thanks, in part, to countries such as India sidelining Huawei and ZTE, and Vietnam blocking Huawei from its telecom networks.

But these dynamics could change. For now, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand remain open to Chinese 5G providers. Singapore, the region’s technology leader, is constructing its own 5G base network and welcomes all vendors to bid in the services marketplace.

Even though decisions on technology and regulation are still being seen in the West through the lens of a great power competition, the picture on the ground is more nuanced and has as much to do with consumer demand as it does national interest.

Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce and payments giant, has controlling stakes in Southeast Asian online retailers Lazada and RedMart and has made significant investments across the consumer value chain. It is now one of the region’s largest e-commerce backers, competing with local unicorns like Gojek and Shopee. Alibaba’s success has come from pursuing an inclusive, rather than exclusive, approach. It has welcomed vendors of all nationalities, shown flexibility by allowing users to pay by credit card instead of forcing them to use UnionPay, and enabled access to the giant Chinese market. Amazon, by contrast, has struggled to gain a strong foothold in the region.

Both Alibaba and Tencent have been instrumental in spurring the growth of digital wallets and payments throughout poorer ASEAN countries, providing essential services for hundreds of millions across the region. Even as China promotes its own technology, it is also enabling greater digital and e-commerce access to its own marketplace.

A customer uses his mobile phone to pay via a QR code with the WeChat app at a market in Beijing, China. Kevin Frayer/Getty Images

A customer uses his mobile phone to pay via a QR code with the WeChat app at a market in Beijing, China. Kevin Frayer/Getty ImagesU.S. tech giants Google and Facebook have stepped up to play too. For both, Southeast Asia is the fastest-growing region for user expansion and advertising. Facebook has reached nearly 600 million daily active users across Asia, and Singapore is the global hub for Google’s “Next Billion” initiative focused on adapting its Android apps and features to the population’s diverse bandwidth speeds and needs. Both want to expand their pilot programs in mobile payments and digital identity across the region. In the arena of digital services, such as cloud computing and business transformation consulting, American players Amazon, Microsoft, and Google are also the region’s leaders — all ahead of Alibaba.

With more than 605 million mobile subscribers, Southeast Asia is clearly a hyperactive digital marketplace. But still, large populations remain unbanked: according to the World Bank, more than half of Indonesians, Filipinos, and Vietnamese lack banking services. As telecoms become the pathway to mobile banking, and mobile banking the pathway to broader consumption, the region is undeniably the world’s greatest untapped market. A rule of thumb in economic modernization is that development accelerates as countries deploy technologies that are better, faster, and cheaper for the masses. China has been there with broadband internet and telecoms. The region would prefer America give them affordable alternatives to Chinese technology than merely scolding them for using it.

Southeast Asian nations are fully aware of all of this jostling at the diplomatic and commercial levels. This mere fact has encouraged them to incrementally push forward with their own regional agenda. Indeed, there is strong evidence that Southeast Asia is, rather than splitting up along Cold War lines, coming together and asserting its collective leverage.

While the ASEAN Framework on Personal Data Protection, a set of principles that promote personal data protection in the region, has no binding authority, numerous governments and companies have committed to the EU’s GDPR data protection regulations, both due to rising services trade with Europe as well as to guard against foreign monopolies. At the same time, ASEAN fragmentation makes it difficult for a single outside player to dominate. Telecommunications and banking remain localized. Efforts toward pan-ASEAN licenses for financial services are ongoing, but their full fruition is still some years away. American, Chinese, and Japanese tech companies and banks have a national presence across the region, but eventual integration will also favor trusted regional banks, such as DBS and Maybank, and telecoms, such as Singtel. Even as the region comes together, it will therefore remain a quilted patchwork.

The lesson is that the great tech stories of Southeast Asia in the years to come are not of China or the U.S. creating technological colonies but rather of their simultaneously capitalizing the region’s homegrown champions.

The outstanding landmark examples include SEA Group — initially funded by American private equity firm General Atlantic and China’s Tencent and now one of the largest companies from the region listed on the NYSE — and Grab, with large stakes by Singapore’s Temasek, Japan’s SoftBank, and China’s Didi Chuxing (whose stake was gained through its absorption of Uber’s regional operations). Indonesia’s Gojek has become the country’s super-app, for everything from ride-sharing to payments, and counts Japan’s Mitsubishi and American firms Google, Facebook, PayPal, Visa, and Sequoia as investors. Tokopedia, one of Indonesia’s leading online marketplaces, is another example of how geopolitical competition takes a backseat to bottom-up financial multi-alignment: Japan’s SoftBank and China’s Taobao are its largest shareholders. VNG Corporation, Vietnam’s first unicorn and leader in gaming, e-commerce, and social media, is another example of a company far too rooted domestically to need to cede ground or supplicate even the largest foreign tech companies. They will have to play by its rules.

There is no doubt that the U.S.-China rivalry will evolve and lurch in the years ahead. There is now a broad, bipartisan American consensus that China cannot be trusted, allies must be reassured, and supply chains must be decoupled. China too will continue its policy of aggressively trying to substitute American imports with homegrown alternatives, its quest for technological self-sufficiency, and its efforts to lure countries into its infrastructural, financial, and technological orbit.

Southeast Asia is a natural location for the two to compete. But it is also among the most ethnically diverse regions on the planet, as well as one of the most politically fragmented. With most countries carefully guarding their hard-won postcolonial sovereignty, they have no intention of bowing to outsiders in their own neighborhood ever again. The region is clearly not a bloc. Rather, it is a sponge, absorbing foreign technology and practices to increase its own weight. The winner of the U.S.-China confrontation may well be Southeast Asia.

No comments:

Post a Comment