Loren Thompson

Donald Trump is the most controversial U.S. president in modern times. Some have seen him as the salvation of a faltering democracy, others as an existential threat to that democracy.

It will be a long time before historians arrive at any kind of consensus concerning the significance of the Trump presidency. However, some consequences of his tenure are already apparent. One of those is the impact he has had on the nation’s defense posture.

Trump has done more in four years to shift the vector of U.S. military preparations than most presidents accomplish in eight. The fact that he did this while the nation was at peace is remarkable. The fact that he often did not know the details of how his defense strategy was being implemented is beside the point (few presidents do).

As President Trump prepares to exit the White House, it is important to see his military legacy clearly, because for better or worse, it is the foundation on which his successor will have to build.

LOREN THOMPSON

Avoiding new wars. Trump is the first president in decades who did not commit the nation to new overseas military campaigns. He shared with President Obama an aversion to such adventures, but Obama launched an Afghan troop surge (2009), an intervention in Libya (2011), a return of forces to Iraq (2014), and a U.S. military role in the Syrian civil war (2014). Trump preferred to use other instruments such as economic sanctions in dealing with threats—even when they were close to home, as in the case of Venezuela, or a danger to regional peace, as in the case of Iran. He thus bought the U.S. military four years of relative peace in which to rebuild from endless wars.

Targeting China. Trump presided over a wholesale revision of national defense strategy that shifted the focus of military preparations from counter-terrorism to great-power rivalries. Although Russia is often described as a “near-peer” rival of America’s military, former defense secretary Patrick Shanahan got it right when he observed that the new strategy is mainly about “China, China, China.” The Middle Kingdom will be the main locus of U.S. military preparations for the foreseeable future, and the need for new weapons is explained primarily in terms of the challenge posed by Beijing.

Rethinking collective security. U.S. leaders have been demanding more burden sharing from allies for two generations. Trump went a step further. He warned countries like Germany and South Korea that if they did not spend more on the common defense, the U.S. would stop protecting them. That included the possibility of no longer providing a nuclear “umbrella” pursuant to a strategy known as extended deterrence. Trump believed the U.S. was assuming great risk and expense for countries that often did not reciprocate, raising doubts about the value of longstanding alliances. President-elect Biden believes otherwise, but once the possibility of a break arises where none previously existed, the reconstruction of confidence is no simple matter.

Revitalizing nuclear deterrence. Trump began his 2016 presidential campaign calling for robust modernization of the nation’s strategic nuclear forces. All three legs of the Cold War nuclear triad—missiles at sea, missiles on land, and long-range bombers—were wearing out and Trump subscribed to the Reagan philosophy of peace through strength. His administration fully funded a modernization plan inherited from Obama without exhibiting any of the latter president’s hesitancy about nuclear weapons. He also funded the first major modernization of the nuclear command-and-control system since the Cold War ended.

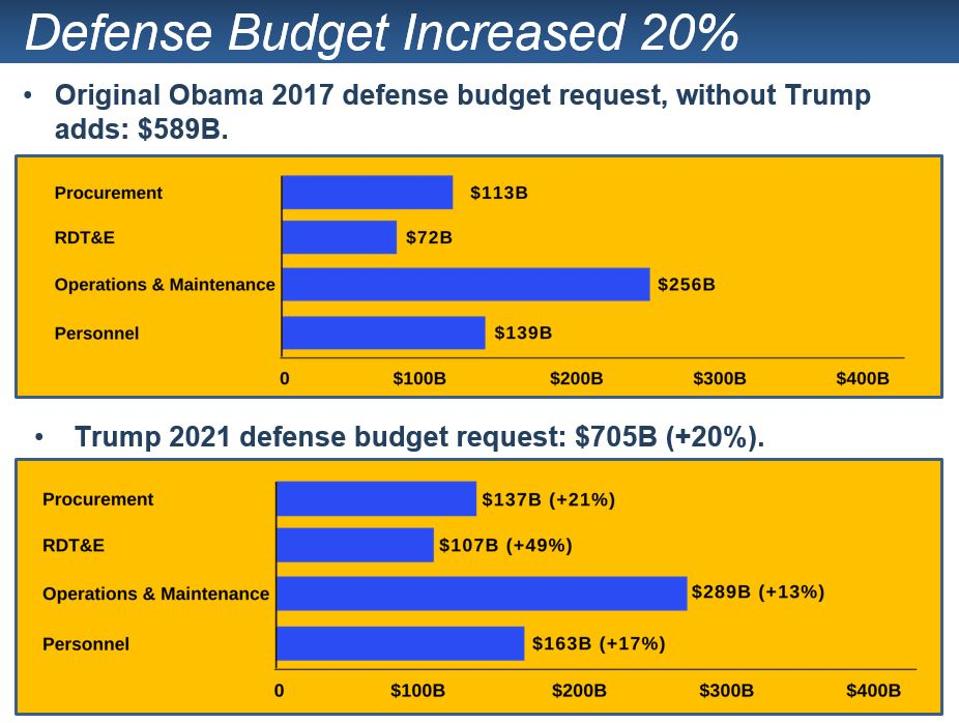

Surging military innovation. Trump increased the Pentagon budget 20% over four years, but the growth was not evenly distributed between readiness, force structure and investment. The big gainer was research and development, which in nominal terms rose 49% between Obama’s last defense request and the Trump 2021 request. This enabled all three military departments to develop next-generation weapons while actively pursuing disruptive technologies such as unmanned submarines (Boeing BA -1.6%) and hypersonic weapons (Lockheed Martin LMT -0.8%). The military embrace of new technologies such as digital engineering has the potential to keep America’s joint force ahead of rivals like China for many years to come.

Organizing for multi-domain operations. A key feature of the Trump national defense strategy is recognition that U.S. military forces will need to conduct future operations across five distinct warfighting domains: air, land, sea, space and cyber. To a greater degree than ever before, the military services are generating doctrine and developing networks that will enable them to cooperate across all five domains for optimal effect. For instance, an airborne threat might be tracked by Navy sensors but intercepted by Air Force weapons. A challenge to naval sea control might be eliminated by Army long-range fires. This kind of cooperative engagement has been discussed for many years, but the funding and motivation to pursue it has grown during the Trump presidency.

Creating a space force. The warfighting domain where American military dominance was most at risk when Trump took office was space. The joint force and the rest of American society had come to rely heavily on orbital assets such as GPS and geospatial intelligence satellites, but China and Russia were developing diverse methods of negating U.S. space capabilities in wartime. The Trump administration launched a series of new programs to bolster space resilience (many of them secret). But it also did something else: it separated development and management of orbital capabilities into a new military service, called the Space Force. The Space Force will remain within the Department of the Air Force, but space now has a powerful advocate in military councils that did not exist before Trump.

Integrating military & economic policy. One of the most unusual developments during the Trump era has been the integration of Pentagon weapons purchases with other facets of national economic policy. The process is by no means complete, but to a much greater extent than in the recent past, arms sales and weapons development are being treated as complementary to an emerging industrial policy aimed at bolstering competitiveness in manufacturing and science. The new approach harkens back to early Cold War years, when military research helped produce marvels such as the internet and digital computers. Because China is viewed as both a military and an economic threat, it was natural to think about defense programs in similar terms.

It is an open question whether any of these changes would have occurred during a Democratic administration. We presumably are about to find out. I’m betting that no matter how much the Biden team dislikes President Trump, it will feel compelled to stick with many of the military trends that define his defense legacy.

No comments:

Post a Comment