ANNE CASE, ANGUS DEATON

PRINCETON – American capitalism is not serving most Americans. While educated elites live longer and more prosperous lives, less-educated Americans – two-thirds of the population – are dying younger and struggling physically, economically, and socially.

The world received the blessings of cutting-edge science this holiday season with the record-fast development of effective COVID-19 vaccines that promise to end a pandemic that has so far killed more than 1.7 million people and caused the worst economic crisis in generations. But the rush by rich-country governments to secure enough doses for their own citizens threatens to prolong the agony for the developing world.

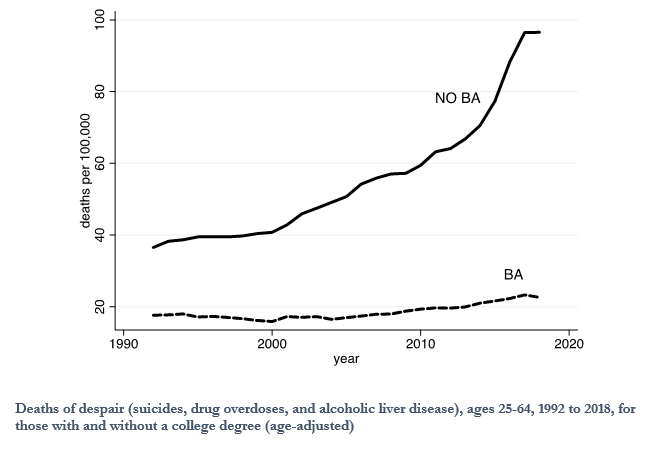

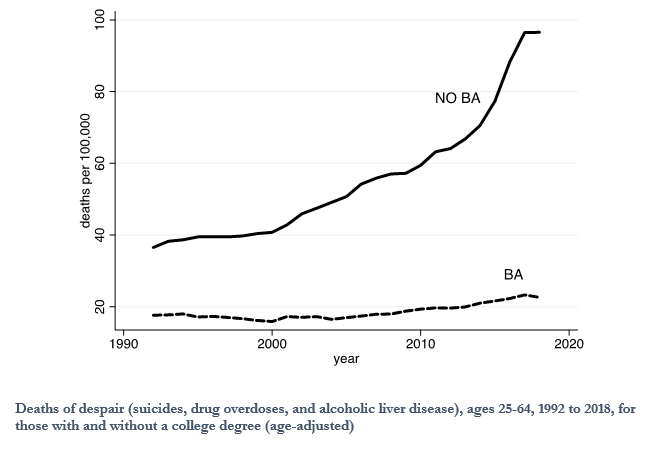

This growing divide between those with a four-year college degree and those without one is at the heart of our recent book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. The rise in deaths that we describe is concentrated almost entirely among those without a bachelor’s degree, a qualification that also tends to divide people in terms of employment, remuneration, morbidity, marriage, and social esteem – all keys to a good life.

The COVID-19 pandemic is playing out similarly. Many educated professionals have been able to work from home – protecting themselves and their salaries – while many of those who work in services and retail have lost their jobs or face higher occupational risk. When the final tallies are in, there is little doubt that the overall losses in life and money will divide along the same educational fault line.

The pandemic is also changing the business landscape, favoring large firms over small ones, and e-businesses over brick-and-mortar firms. Many of the large firms – especially Big Tech – employ few workers relative to their market valuations, and do not offer the good jobs that once were available to less-educated workers in old-economy companies.

These changes in the nature of employment have been ongoing for many years, but the pandemic is accelerating them. The share of national income accruing to labor has been – and will continue to be – in long-term decline, which is reflected in today’s record-high stock market. The market’s bull run during a pandemic illustrates, once again, that it is an indicator of expected future profits (not national income): stock prices rise when labor’s share of the pie shrinks.

Depending on how quickly and widely the recently approved COVID-19 vaccines are administered, some of these trends will be reversed, but only for a while. What death toll can America expect for 2021? The United States has already recorded more than 340,000 deaths from COVID-19 in 2020, and total excess deaths – including COVID-19 deaths that were not classified as such, and deaths from other cases that were indirectly caused by the pandemic – are about a quarter larger.

Moreover, even if vaccines are widely distributed by mid-2021, there could be several hundred thousand more pandemic-related deaths in the US before all is said and done, not to mention the additional deaths that could have been prevented by early detection or treatment of other illnesses that were missed during the pandemic.

In any case, we can at least look forward to a future in which COVID-19 has receded as a major cause of death in the US. The same cannot be said for deaths of despair (suicide, accidental drug overdose, and alcoholic liver disease), of which there were 164,000 in 2019, compared with the past “normal” US level of roughly 60,000 per year (based on data from the 1980s and early 1990s).

Although drug overdoses rose in 2019, and were rising in 2020 before the pandemic, predictions of mass suicides during lockdowns have not yet been verified in any country, nor do we expect them to be.

In our past work, we showed how suicides and other deaths of despair tracked with the slow destruction of working-class life since 1970. It is now entirely plausible that deaths in the US will rise again as the structure of the economy shifts after the pandemic. For example, cities will likely undergo radical change, with many businesses moving out of urban high-rise buildings and into suburban low-rises. If there is less commuting as a result, there will be fewer service jobs maintaining buildings and providing transportation, security, food, parking, retail, and entertainment. Whereas some of these jobs will move, others will simply vanish. And while there will be entirely new jobs, too, there is sure to be much disruption in people’s lives.

Overdoses today are largely from illegal street drugs (fentanyl and heroin), rather than from prescription opioids, as in the recent past, and this particular epidemic eventually will be brought under control. But, because drug epidemics tend to follow major episodes of social upheaval and destruction, we should be prepared for new ones in the future.

The US economy has long been experiencing large-scale disruption, owing to changes in production techniques (especially automation) and, to a lesser extent, globalization. The inevitable disturbances to employment, especially among less-educated workers who are most vulnerable to them, have been made vastly worse by the inadequacy of social safety nets and an absurdly expensive health-care system. Because that system is financed largely by employer-based insurance, which varies little with earnings, it places the greatest burden on the least skilled, who are priced out of good jobs.

No comments:

Post a Comment