Taras Kuzio

Since 1991, there has been an in-built tension in Russian-Ukrainian relations, because ‘the more Ukraine asserted its sovereignty, the more Russia questioned it, and vice versa’ (D’Anieri 2019, 63). The 2014 crisis cannot be understood without ‘looking at its long-term sources’ because to do so would be to tackle them ‘out of context and therefore to misinterpret them’ (D’Anieri 2019, 253). The sources of the 2014 crisis lie in Russia’s inability to recognise Ukraine and Ukrainians, which hark back to the early 1990s. The 2014 Russian-Ukrainian crisis is not fundamentally different from the many disagreements the two sides have had since December 1991 (D’Anieri 2019, 265–266).

This chapter is divided into two sections. The first section analyses the impact of Russian annexation and military aggression on the disintegration of Ukraine’s ‘east,’ which comprised eight southeastern Ukrainian oblasts prior to 2014; the replacing of the Soviet concept of Russians and Ukrainians as close, but different ‘brothers’ with the Tsarist Russian and White émigré denial of Ukraine and Ukrainians, which particularly impacted upon Russian-speaking eastern Ukrainians; and the collapse in Russian soft power in Ukraine. The second section discusses the prospects for a peaceful settlement of the Russian-Ukrainian War. Former President Poroshenko was never the obstacle to peace, and President Zelenskyy will not become the harbinger of peace because the roots of the Russian-Ukrainian War do not lie in the choice of Ukrainian president, but rather in Russian nationalist (imperialist) attitudes towards Ukraine and Ukrainians, which will remain as long as Putin is de facto president for life.

Impact of the War

Pro-Russian Ukrainian ‘East’ is No More

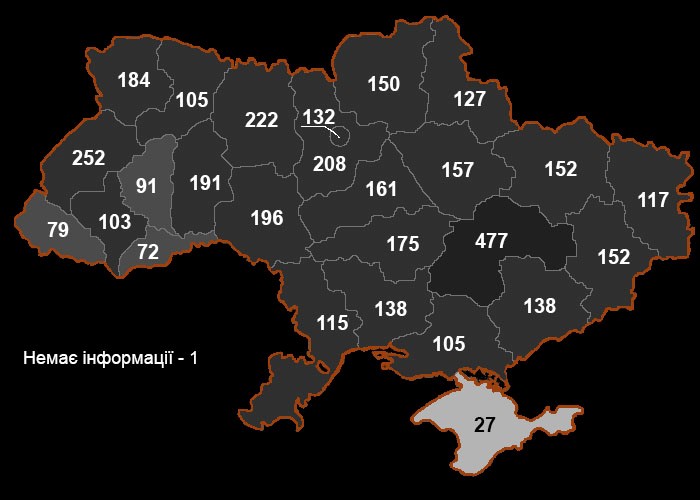

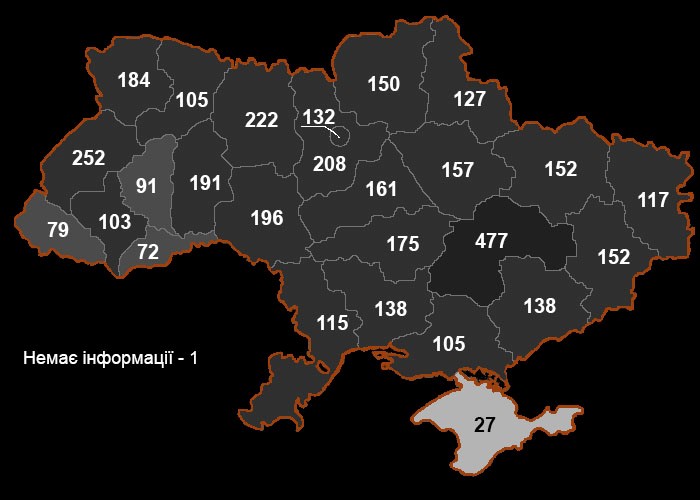

Russian-speaking southeastern Ukrainians have undertaken the majority of the fighting against Russian and Russian proxy forces, and they account for the highest rate of casualties of Ukrainian security forces. Over two million IDPs and refugees are Russian speakers from the Donbas. Russia is not fighting ‘western Ukrainian nationalists,’ but is primarily killing, wounding, and harming Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Eastern Ukraine has the highest proportion of military veterans and the highest rate of casualties among Ukrainian security forces (see 6.2 map).

6.1. Photographs in Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk Oblast of Ukrainian Security Forces Killed in the Russian-Ukrainian War.

Source: Author’s photographs.

Note: Top photograph:long wall alongside Kyiv’s Mykhayivskyy Zolotoverkhnyy Monastyr (St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery) with photographs of Ukrainian security forces killed in the Russian-Ukrainian war; bottom left photograph: one section of the large military cemetery in the city of Dnipro of Ukrainian security forces killed in the Russian-Ukrainian war; bottom right photograph: one of the many glass obelisks in the Alley Heroyiv (Alley of Heroes) in the centre of the city of Dnipro dedicated to the Nebesna Sotnya (Heavenly Hundred) killed during the Euromaidan Revolution and Ukrainian security forces killed in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Russian information warfare and Putinversteher scholars (Sakwa 2015, 2017; Cohen 2019) depict volunteer battalions as dominated by extreme right ideologies and western Ukrainians; in fact, they were largely filled by Russian speakers and national minorities (Aliyev 2020). Huseyn Aliyev (202) writes that ethnic nationalism was ‘one of the least probable causes of wartime mobilization.’ Azov and Pravyy Sektor battalions, the two battalions demonised for their ‘nationalist’ ideologies most often, included Georgians, Jews, Russians, Tatars, and Armenians.

6.2. Map of Ukrainian Security Forces Killed in the Russian-Ukrainian War by Oblast

Source: http://memorybook.org.ua/indexfile/statbirth.htm. Used with permission.

Note: Total of 4,270 known casualties as of 1 March 2020. Note the highest number of 477 casualties in Dnipropetrovsk oblast.

Six years of Russian military aggression have changed Ukraine, Ukrainian views of Russia, and Ukrainian-Russian relations. Russia’s annexation of Crimea and on-going military aggression in eastern Ukraine have two long-lasting consequences for scholarly research on Ukraine. The first consequence is the disappearance of a pro-Russian ‘east,’ and the second consequence is the collapse in Russian soft power. Since 2013, Russian policies have been counter-productive and have deepened Ukraine’s break with Russia.

Tatyana Zhurzhenko (2015, 52) writes that 2014 represented a ‘new rupture in contemporary history, a point of crystallization for identities, discourses, and narratives for decades to come.’ Ukraine’s fault line is no longer east versus west, but Ukraine versus the Donbas. Medical volunteer Natalya Zubchenko, based in the city of Dnipro, said, ‘We don’t think of ourselves as east or west. We’re central’ (Sindelar 2015). The fracturing of Ukraine’s ‘east’ and the reduction to two Donbas oblasts represent ground-breaking changes in Ukrainian identity and the country’s regional configuration (Zhurzhenko 2015; Kuzyk 2018; Kulyk 2016, 2018, 2019).

The collapse in pro-Russian sentiments and growth in Ukrainian patriotism in Dnipropetrovsk created a ‘domino effect,’ which spread to neighbouring regions because of the oblast’s industrial power and size. Opinion polls show that there is now a belt of four oblasts – Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Kherson, and Mykolayiv – within the former eight pro-Russian oblasts of southeastern Ukraine that no longer hold pro-Russian views or pro-Russian foreign policy orientations. Changes in Kharkiv and Odesa were not as dramatic, but even there, pro-Russian sentiment has declined. Ukrainian identity is also growing in Ukrainian-controlled Donbas (Sasse and Lackner 2018; Haran, Yakovlyev and Zolkina 2018).

Russian speakers in Ukraine are loyal to a multi-ethnic country where the Russian and Ukrainian languages are both spoken and disloyal to the Russian World. This is reflected in three-quarters of Ukrainians describing the conflict as a Russian-Ukrainian War (Poshuky Shlyakhiv Vidnovlennya Suverenitetu Ukrayiny Nad Okupovanym Donbasom: Stan Hromadskoyii Dumky Naperedodni Prezydentskykh Vyboriv 2019). Russia’s invasion led Russian-speaking Ukrainian patriots to view DNR and LNR leaders as Russian puppets; that is, Russian proxies (Aliyev 2019).

Until 2014, centrist Ukrainian and Russian speakers were not anti-Russian and adhered to the Soviet concept of Ukrainians and Russians being closely related, but different ‘brothers.’ They would never accept the Tsarist Russian and White émigré view of Ukrainians as one of three branches of the ‘All-Russian People’ and the non-existence of a Ukrainian state.

Putinversteher scholars believe that peace can be achieved in the Donbas by Ukraine embracing its ‘bicultural’ Ukrainian-Russian identity (Petro 2015, 33). Hahn (2018, 176) agrees with Russian leaders that left- and right-bank Ukrainians and Russians are a ‘single nation,’ ‘having common historical roots and common fates, a common religion, a common faith, and a very similar culture, languages, traditions and mentality.’ The failure of Putin’s ‘New Russia’ project shows that Ukraine never had a ‘bi-cultural’ identity, and adopting Petro’s (2015) proposals would have been impossible prior to 2014 and, after six years of war and bloodshed, his proposal is illusory.

Low levels of Ukrainian allegiance to the Russian World were already evident before the 2014 crisis (Wawrzonek 2014) and in 2014. A majority of Ukrainians in southeastern Ukraine did not believe that they were part of the Russian World. Of Ukraine’s eight southeastern oblasts, the Russian World was thoroughly unpopular in Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Kherson, and Mykolayiv, had only slightly higher support in Kharkiv and Odesa, and had the highest support in the Donbas. Overall, only 27.4% in southeastern Ukraine felt that they belonged to the Russian World (O’Loughlin, Toal and Kolosov 2016, 760). Russian military aggression ‘killed any appeal’ for the Russian World in Ukraine (Plokhy 2017, 345).

In spring 2014, Russia’s strategy to organise pro-Russian rallies that would capture official buildings, declare non-recognition of the Euromaidan government’s authority, and establish ‘people’s republics,’ which would seek protection through Russian military invasion, had low levels of support throughout southeastern Ukraine (The Views and Opinions of South-Eastern Regions Residents of Ukraine 2014). If Russia had invaded eastern Ukraine to ‘protect’ Russian speakers, only 7% in southeastern Ukraine would have greeted these Russian troops (The Views and Opinions of South-Eastern Regions Residents of Ukraine 2014).

Russians and Ukrainian are No Longer ‘Brothers

The 1863 thesis of tryedynstva russkoho naroda was revived in a refashioned form after 1934, when Ukrainians and Russians were presented as different, but at the same time close ‘brotherly peoples’ whose fate was forever bound together. During Putin’s presidency, Russian discourse and policies towards Ukraine stagnated from this Soviet ‘brotherly peoples’ concept to the Tsarist Russian and White émigré concept of tryedynstva russkoho naroda, which considers Ukraine an artificial state, Ukrainians and Russians as ‘one people,’ and Ukraine as including ‘Russian lands’ that were wrongly allocated by the Soviet regime. Such views have always had very limited support in Ukraine outside of Crimea and the Donbas.

It is also important to remember that sharp breaks in 1991 and 2014 followed changes that had taken place earlier. In 1991, the disintegration of the USSR and Ukrainian independence came after six years of civil strife, nationalist mobilisation, splits in the Soviet Communist Party of Ukraine, and opposition success in Soviet Ukrainian and local elections. The 2014 crisis similarly came after a quarter of a century of nation-building in an independent Ukrainian state, and the growing importance of national identity and memory politics following the Orange Revolution. Ukrainian nation-building progressed rapidly after 1991 and 2014, but this development had been set in motion by earlier periods of slower changes in identity.

The official Soviet historiography of Kyiv Rus as the joint inheritance of three eastern Slavs remained influential until the Orange Revolution. In a 2006 opinion poll asking which statement they supported, 43.9% of Ukrainians agreed that Ukrainian history was an integral part of eastern Slavic history, while 24.5% believed that Ukraine had exclusive title to Kyiv Rus (Rehionalni Osoblyvosti Ideyno-Politychnykh Orientatsiy Hromadyan Ukrayiny v Konteksti Vyborchoyi Kampanii 2006, 5). A decade later, this had changed, and 59% of Ukrainians believed that Kyiv Rus and other historical developments were exclusively Ukrainian, with 32% continuing to believe that Ukrainian history is part of eastern Slavic history (Konsolidatsiya Ukrayinskoho Suspilstva: Vyklyky, Mozhlyvosti, Shlyakhy 2016). Two years later, another poll found that 70% of Ukrainians believed that Ukraine is the exclusive successor to Kyiv Rus (rising from 54% in 2008), with 9% disagreeing (Dynamics of the Patriotic Moods of Ukrainians 2018). Within twelve years, the number of Ukrainians who claimed exclusive title to Kyiv Rus history had nearly tripled from 24.5% to 70%.

Five years after Russia launched its military aggression against Ukraine, only voters for the pro-Russian Opposition Platform-for Life (88%) believed that Ukraine is part of eastern Slavic history. Most of these voters live in the shrunken ‘east’ of Ukrainian-controlled Donbas. Most voters for the Fatherland Party (Batkivshchina, 62%), Zelenskyy’s Servant of the People Party (Sluhu Narodu, 61%), Voice Party (Holos, 54%), and Poroshenko’s European Solidarity Party (Yevropeyska Solidarnist, 54%) do not believe that Ukrainian history is part of eastern Slavic history (Ukrayina Pislya Vyboriv: Suspilni Ochikuvannya, Politychni Priorytety, Perspektyvy Rozvytku 2019). Could we deduce from this that Zelenskyy’s voters are more ‘nationalistic’ than those who support Poroshenko?

The Soviet ‘brotherly peoples’ concept gave eastern Ukrainians and Russian speakers a Ukrainian identity and a close relationship to Russia. Russian-Ukrainian ‘brotherly’ relations were undermined by the rehabilitation of Tsarist Russian and White émigré views of Ukrainians, and by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine. This was reflected in the outrage present in Anastastiya Dmytruk’s poem at the beginning of this book, which says that Russians will no longer be the brothers of ‘Ukrainians.’

Vasyl Kremen and Vasyl Tkachenko (1998, 18), two political consultants in President Kuchma’s team, stressed that unity in Kyiv Rus ‘does not mean “eternal unity” of the three eastern Slavic peoples.’ Plokhy (2017, 346) concludes, ‘The imperial construct of a big Russian nation is gone, and no restoration project can bring it back to life, no matter how much blood and treasure may be expended in the effort to revive a conservative utopia.’ By 2018, 66% of Ukrainians believed they had been brothers with Russians, but this was no longer the case, while another 16% believed that Russians and Ukrainians had never been brothers (Mishchenko 2018). This means that a high 82% of Ukrainians no longer view Russians as their ‘brothers’ (Kulchytskyy and Mishchenko 2018, 192).

The first nuclear bomb against Russian-Ukrainian ‘brotherly’ relations detonated around Crimea. Plokhy (2017, 345) writes: ‘The Russian World was now associated not just with Pushkin and the Russian language but with a land grab that had cost thousands of dead and wounded and disrupted millions of lives.’ Putin’s (2020c) claim that Russia’s annexation of Crimea was not the reason why relations with Ukraine were poor is untrue, because Crimea was one of the central components of the Soviet nationalities policy of Russian-Ukrainian ‘brotherhood.’ In 1954, the peninsula was transferred from the Russian SFSR to Soviet Ukraine on the symbolically important 300th anniversary of the reunion of Ukraine and Muscovy in the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav.

The second nuclear bomb detonated in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Putin chose Ukrainian Independence Day to invade Ukraine in 2014. Russian speakers who joined Ukrainian volunteer battalions viewed Russian-controlled Donbas as run by ‘gangsters’ that misrepresented Ukraine (Aliyev 2019). They were especially resentful at Russia’s invasion in August 2014, which for them crossed a ‘red line’ and turned the conflict into a Russian-Ukrainian War.

Putin offered ‘guarantees’ for the withdrawal of Ukrainian forces, who were surrounded by an invading Russian force. Putin lied and, near the Donetsk oblast town of Ilovaysk, Russian forces killed 366 Ukrainian soldiers, wounded 429, and took 300 prisoners. The General Prosecutor’s Office of Ukraine described Putin’s maskirovka as a war crime and sent the case to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. An additional war crime was ‘Russian servicemen and the irregular illegal armed formations under their control’ who murdered and wounded Ukrainian soldiers. Ilovaysk buried Ukrainian-Russian ‘brotherhood.’

15% of Ukrainian voters are veterans of the Donbas War or are family members of veterans. By the end of Putin’s term in office in 2036, a far higher proportion of Ukrainian voters will be veterans of the Donbas War. Veterans are very active in civil society and party politics.[1] Streets and roads have been renamed throughout Ukraine in honour of Ukrainian soldiers who have died fighting in the Donbas. New sections of cemeteries for casualties of Ukrainian security forces who died fighting in the Russian-Ukrainian War are now commonly found alongside graves of Soviet soldiers who fought in the Great Patriotic War and in Afghanistan, and Ukrainian nationalists who fought for the Western Ukrainian People’s Republic (ZUNR) and Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA). As of December 2019, 523 plots of Ukrainian soldiers killed in the Russian-Ukrainian can be found throughout Ukraine, containing a total 1,636 graves.

Military casualties and veterans of the war increase support for radical post-Euromaidan memory politics, breaking with Soviet and Russian interpretations of Ukrainian history and Ukraine’s divorce from Russia (Identychnist Hromadyan Ukrayiny v Novykh Umovakh: Stan, Tendentsii, Rehionalni Osoblyvosti 2016). In 2016, 69% of veterans, compared to 46% of Ukrainians overall, condemned the Soviet regime and backed the prohibition of communist symbols. Meanwhile, 58% of Donbas War veterans supported one of four de-communisation laws (Law No. 314-VIII) providing legal status and honouring those they consider to be their predecessors in the fight for Ukrainian independence (Identychnist Hromadyan Ukrayiny v Novykh Umovakh: Stan, Tendentsii, Rehionalni Osoblyvosti 2016). Veterans and soldiers of the Russian-Ukrainian War are largely in the 20–45 age group, which also makes them more radical proponents of Ukrainian identity and negative towards Russia. More Ukrainians under the age of 59 support (than oppose) one of the de-communisation laws banning communist and Nazi symbols and denouncing the USSR and Nazi Germany as totalitarian states. Only the 60–69 and above 70 age groups had higher numbers of opponents than supporters of de-communisation (Shostyy rik dekomunizatsii: stavlennya naselennya do zaborony symboliv totalitarnoho mynuloho 2020).

Russia’s invasion had its greatest impact upon eastern Ukrainians, such as Russian-speaking Anatoliy Korniyenko, whom I interviewed in the city of Dnipro in 2019 and 2020. His 22-year-old son Yevhen had been killed in the Russian-Ukrainian War on 12 August 2014, and Anatoliy Koniyenko volunteered for combat duty at the age of 58 (the last time he had served was in the Soviet army in the 1970s). He served four years on the Ukrainian-Russian front line. I asked him why he had enlisted, to which he replied, ‘I wanted revenge.’ There are very many Korniyenko’s in Ukraine, particularly in the east and south, who have lost loved ones to Russian military aggression or who have friends who have lost family members in the war.

No comments:

Post a Comment