By George Friedman

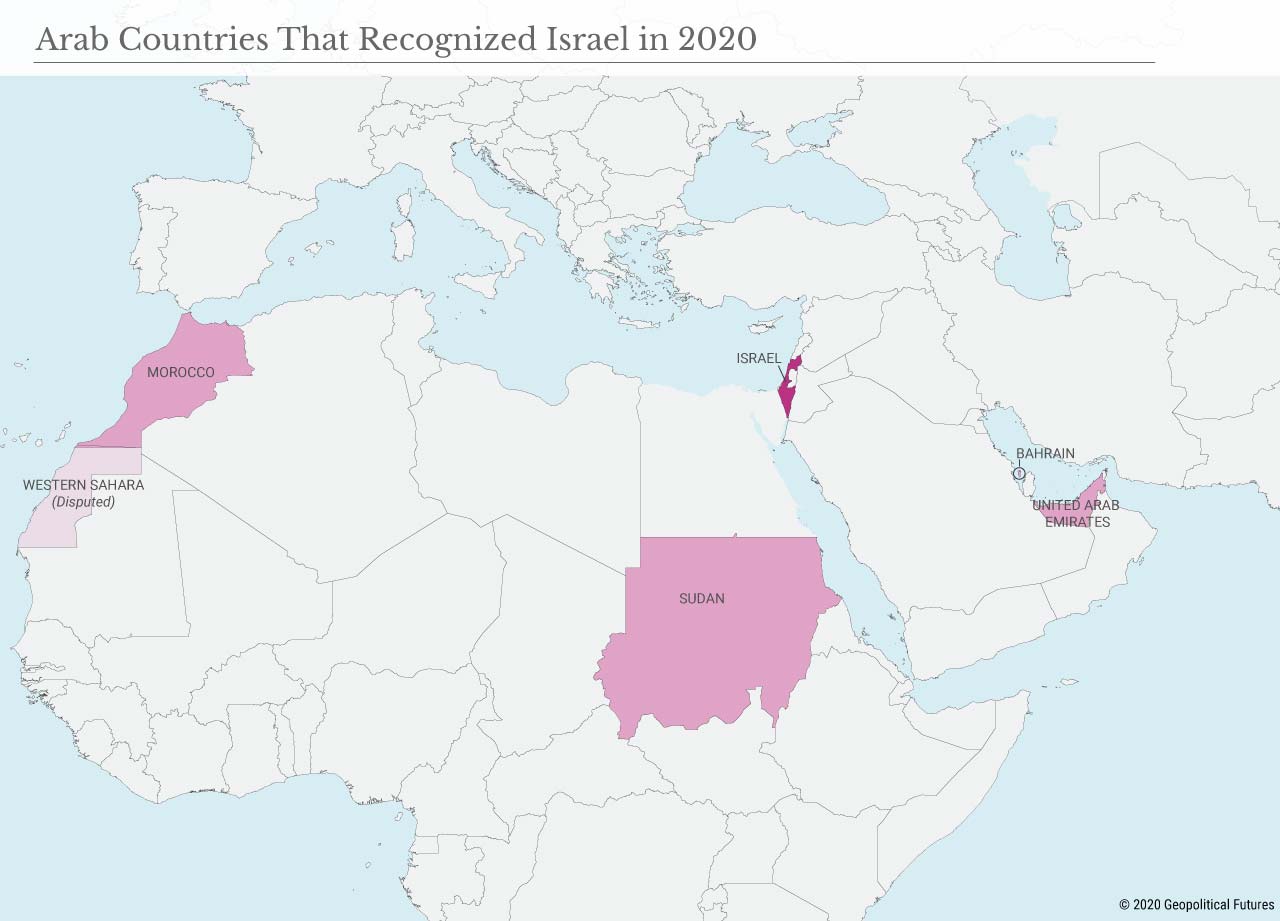

Last week, Morocco established diplomatic relations with Israel, joining three other Arab countries – the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Sudan – that normalized ties this year. In Morocco’s case, part of the deal was U.S. recognition of Morocco’s claim to Western Sahara, just as it had agreed to remove Sudan from its list of state sponsors of terrorism.

This process, which began with the UAE, is rooted partly in a paradox of U.S. Middle Eastern policy. The United States has played an important role in implicitly endorsing the process and occasionally throwing a sweetener on the table. But the United States also made it clear that it was withdrawing its forces from the region and reducing its commitments. That left the region without the power that held it together. Public hostility among nations in the region, and especially with Israel, was possible while the U.S. served as coordinator and bridge. These countries could and did work together but only through secret contacts and U.S. coordination. Without the United States, each state was left to either go it alone or form meaningful relations on the whole. U.S. policy forced the countries of the region to face a reality they had tried to hide: They needed each other.

They needed each other because the Sunni Arab world had enemies, none more dangerous to their interests than Iran. The Arabs framed their policy on the assumption that the United States would guarantee their interests, and even their existence, against an Iranian threat. That remains possible, but what the United States has done is create a critical uncertainty. Iran cannot be sure of what the United States would do under any particular circumstances. Neither can the Arabs. Each has to prepare itself for an absent United States, rather than simply assume an American reaction.

At the same time, the Iranians have a weakened position. One of their strategies was to play off Arab states against Israel, the United States or each other. They could also take advantage of conflicts that periodically flared up between fragmented Arab states. Now Iran has less room to maneuver, while the Arabs find themselves needing to negotiate with neighbors rather than offload risk and responsibility to the United States.

The decision to open diplomatic relations by itself would not normally create an alliance. The U.S. and China have diplomatic relations; they are not allies. But in the case of the Arab world, the matter is different. Within each country, there are factions that are hostile to Israel. Any regime that opens relations with Israel must face this reality. The threat here is internal, and each state that has recognized Israel has broken a barrier. In the U.S. and Israel, this is a welcome break. Among many Arabs, it is a violation of what has been a fundamental principle. Saudi Arabia, wary of the intense feelings on such matters in a significant sector of society, has not taken the step of recognizing Israel, even though it has cooperated with Israel for quite a while. Given the politics of the region, recognition may as well be an alliance. There is little to lose and much to gain for Arab states that have recognized Israel.

The implicit alliance leaves Iran in an extremely difficult position. The Arab world was hostile in many ways before. Now it is organized around Israeli power, making Israel even more dangerous to it. In addition to ruinous sanctions, internal political tension and the potential threat of the United States, it now faces the possibility not only of Arab hostility but of Arab alignment with Israel. In many ways, this is the worst-case scenario for Iran, and the intelligence services arrayed against it will do all they can to encourage the internal opposition.

Iran’s counter is a serious one. The recognition process leaves the Palestinians isolated from their former allies. Iran can portray itself reasonably as the only champion of the Palestinians and the only true enemy of Israel. The Arab states have regarded Palestine as a side issue for a long time. But the same is not always true for their citizens. Iran’s move is to adopt the Palestinian cause as its own, and speak to the Arab public in terms of the betrayal of the Palestinians and capitulation to Israel.

It is not clear that any Arab regime will be forced to change policy or be overthrown. On the other hand, it is not clear that Iran’s formal isolation will cause regime change. But what is clear is that if Iran undertakes military action of any sort against states that have recognized Israel, Israel will be free, and even welcomed, to undertake disproportionate retaliation. And any Iranian allies in the region, such as those in Syria or Iraq, would face the same.

What this move has done is to vastly widen the circumstances under which Israel can attack Iran without facing condemnation in the Arab world. The balance of power has shifted dramatically in the region since the 1970s, when it was Israel facing unified hostility. Now it is Iran that faces hostility. How unified it will be remains to be seen. Unity is rare in the Arab world, but the risks to Arab regimes of both participating in and destabilizing the emerging structure would be too great. Many things could go wrong, but it is a profound redefinition of the Middle East, however it goes.

No comments:

Post a Comment