By Geopolitical Monitor

The list of mutual recriminations between Turkey and Saudi Arabia is a long one, but the two erstwhile US allies have generally managed to keep their hostility within acceptable bounds. A growing, government-backed movement to boycott Turkish goods in the Kingdom suggests that this could well be changing.

A decade of bilateral drift

The governments of Saudi Arabia and Turkey have occupied opposing sides of international crises at several points of the past decade.

The rift first opened in 2011 when a rash of popular protests broke out across the Arab world – the “Arab Spring.” Turkey widely embraced the protests and became a prominent backer of the Muslim Brotherhood and political Islam in general, many of whose proponents viewed Ankara as a role model. For an Islamic theocracy like Saudi Arabia however, the Arab Spring represented an existential threat, and the Kingdom responded by pushing back (and against Turkey’s proxies) on all fronts.

While many of these Arab Spring movements eventually fizzled out with their original ambitions unrealized, the same fault lines surfaced once again in 2017, when Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the UAE, and Bahrain instituted the blockade of Qatar – another state ally of the Muslim Brotherhood. Turkey, along with Iran, would eventually come to Qatar’s aid with diplomatic support and much-needed imports of essential goods, blunting the more serious economic effects of the blockade.

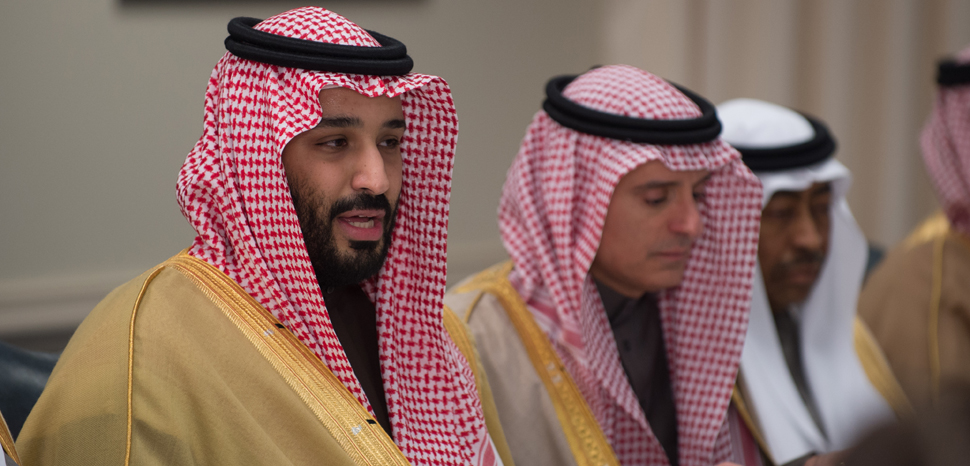

The next and arguably most decisive breach occurred when Saudi dissident Jamal Khashoggi was assassinated at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018. Some 26 Saudi nationals have been tried in absentia in Turkish courts over the killing. President Erdogan has also made vague accusations of the operation being authorized at the highest levels of the Saudi government, though he has stopped short of directly naming any royal family members, likely out of a desire to insulate the bilateral fallout at a time when the United States government was unwilling to push back on its longstanding ally in Riyadh. Still, President Erdogan hasn’t shied away from re-litigating the Khashoggi incident, nor has he endeared himself to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman with public allusions to a rogue ‘shadow state’ operating within Saudi Arabia.

Enter the boycott

Then something strange happened in 2019: reports began to emerge of an unofficial embargo against Turkish exports being enforced by Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies. Much like the boycott currently being urged by President Erdogan against French goods, it seems as though there are behind-the-scenes pressures being exerted on Saudi businesses to boycott any and all Turkish exports.

Though these pressures first manifested sometime last year, lately they have been intensifying and coming into the open. For example, last week, Saudi Prince Abdurrahman Bin Musa’ad Al-Saud called for the boycott to continue until “Ankara reviews its policies on the Kingdom.” This comes after Ajlan al-Ajlan, head of the Saudi Chamber of Commerce, called for the boycott of “anything Turkish” in early October.

Other recent examples include four of the Kingdom’s major supermarkets announcing that they wouldn’t be carrying Turkish goods in the future. Then there’s the sudden appearance of signs in various shops in Riyadh imploring customers to avoid Turkish goods.

Calls to boycott have also appeared on social media, with hashtags like “#Boycott_Turkish_Products” and “Turkish_Products_Boycott_Campaign” trending over the past month. Though before ascribing any popular legitimacy to the movement, it’s worth noting that Saudi social media trends have generally remained in lockstep with government messaging during the MBS era.

Saudi Arabia absorbed some $3.1 billion’s worth of Turkish exports over the course of 2019, with food, clothing, tobacco, and construction materials constituting most of the trade. So far through 2020, Turkish exports to the Kingdom stand at $1.9 billion through August, down by around $400 million at the same point last year; however, it’s hard to determine whether flagging exports are the result of COVID-19 or the Saudi boycott. Just $1.9 billion worth of Saudi exports went the other way to Turkey in 2019.

A struggle for regional – and religious – hegemony

The boycott movement can be viewed as another assertive move on the part of MBS, whose Yemen campaign and (presumable) authorization of the Khashoggi assassination is garnering him a reputation for advancing a bold, if at times reckless, foreign policy for the Kingdom.

Saudi-Turkey acrimony is longstanding, but the boycott comes at a time of particular weakness on the part of Turkey (more on this in a recent situation report). It appears as though MBS is trying to ‘kick Turkey while its down,’ and in doing so can claim that the economic effects (blunted though they are at present) are the result of COVID-related disruptions. This also comes at a time when President Erdogan is making efforts to project an image of bilateral harmony, likely in full realization that Turkey can ill afford another diplomatic fire to have to put out.

The sum of all of these parts is worsening Saudi-Turkey relations, with potential geopolitical ramifications in a region that’s already in flux. One possible outcome is a US-Saudi-Israel-GCC axis in opposition to a Turkey-Iran-Qatar bloc. These external power dynamics would also dovetail with Saudi Arabia and Turkey’s opposing pitches for the hearts and minds of people throughout the region and the Islamic world. Interestingly, as others have pointed out, MBS’ concerns over Turkish influence extends to the realm of soft power and cultural exports, and the Saudis have even deployed a kind of ‘historical warfare’ to contest the Ottoman legacy in the Islamic world.

One final note is that these informal boycotts, deniable at the highest levels yet eagerly encouraged by top-down nationalist appeals, are set to become increasingly common going forward, and can be viewed as a symptom of the breakdown of the WTO-headed global trade system.

No comments:

Post a Comment