By George Friedman

In 2005, in a speech delivered in front of Russia’s Federal Assembly, Russian President Vladimir Putin said that the fall of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe in Russia’s history. What he meant is that the fragmentation of the Soviet Union would cost Russia the element that had allowed it to survive foreign invasions since the 18th century: strategic depth.

For a European country to defeat Russia decisively, it would have to take Moscow. The distance to Moscow is great and would wear down any advancing army, requiring reinforcements and supplies to be moved to the front. As they would advance into Russia, the attackers’ forces would be inevitably weakened. Hitler and Napoleon reached Moscow exhausted. Both were beaten by distance and winter, and by the fact that the defenders were not at the end of their supply line.

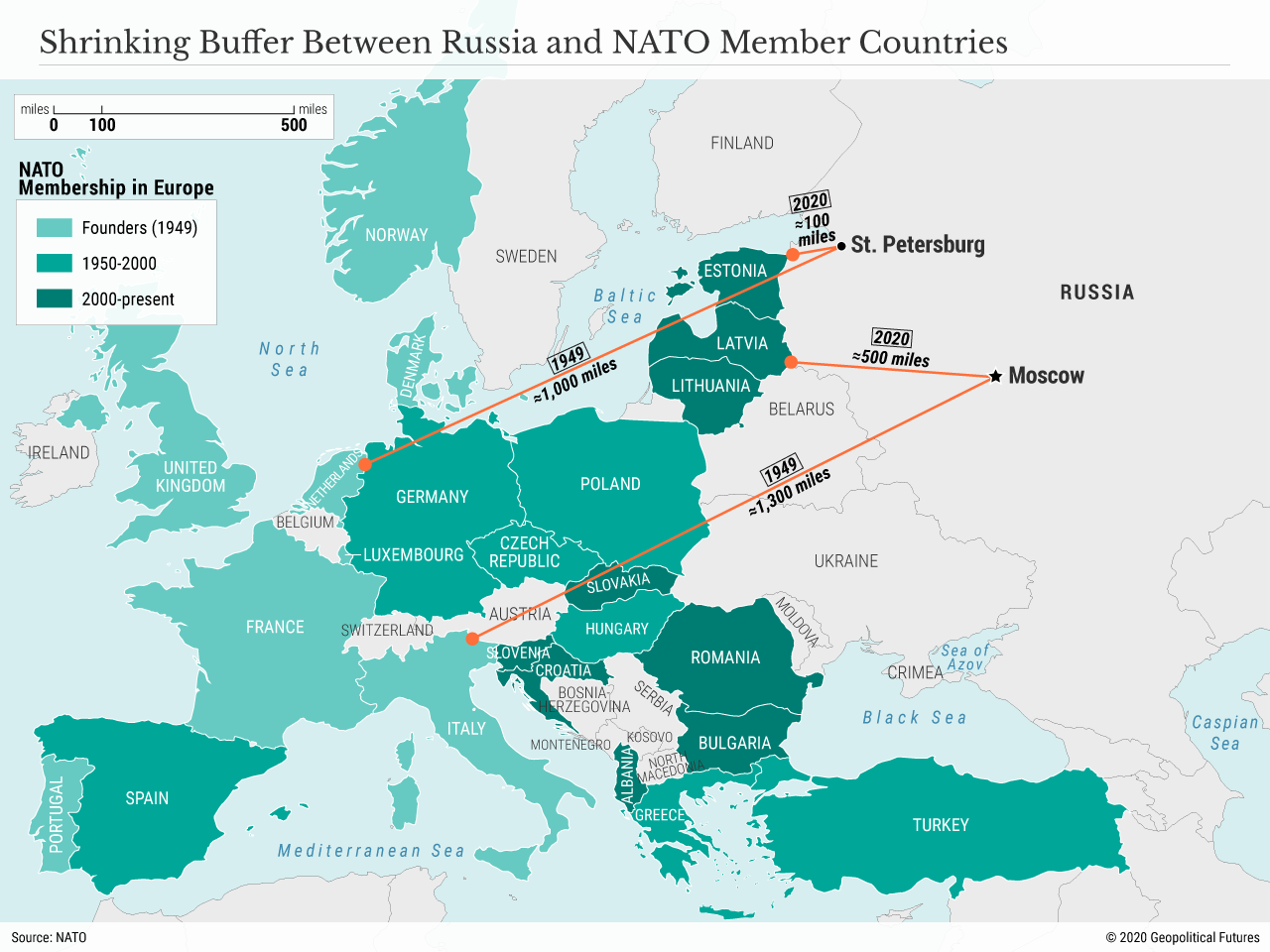

At the height of the Cold War, St. Petersburg was about 1,000 miles from NATO forces, and Moscow about 1,300 miles. Today, St. Petersburg is about 100 miles away, and Moscow about 500 miles. NATO has neither the interest nor the capacity to engage Russia. But what Putin understood was that interest and capacity change and that the primary threat to Russia is from the west.

There is another potential entry into Russia from the south. The Russian Empire used this route as a buffer zone with Turkey, especially during the numerous Russo-Turkish wars. Russia was protected by the Caucasus, a rugged, mountainous region that discouraged any attacks to the point that NATO never considered this option. But if anyone managed to force their way through the mountains, they would be about 1,000 miles from Moscow on flat, open terrain in far better weather than attackers from the west would face.

The Caucasus consists of two mountain ranges. The northern is far more rugged. The southern is somewhat less daunting. The North Caucasus contains Chechnya and Dagestan, both of which contain Islamist separatists. Chechnya, at the center of the northern range, posed a serious challenge to Russia, and one that Putin defeated early in his presidency.

What was most frightening to Putin was that the South Caucasus, consisting of Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan, had left Russia and formed independent states. Russia maintained an alliance with Armenia, the weakest of the three, and complex relations with Azerbaijan, a prosperous oil producer. Georgia, which faced the northern range on a broader front than the others, aligned with the United States.

If the South Caucasus states formed an anti-Russia coalition, and the United States, for example, supported a rising in the North Caucasus, the barrier might be shattered and a path northward opened. Therefore, Russia followed a strategy of imposing strong controls in the North Caucasus while engaging in a war in 2008 with Georgia, its most significant southern threat, based on geography and Georgia’s alliance with the U.S. The war demonstrated the limits of American power while it was engaged in wars in the Muslim world. It was a successful strategy save for the fact that the long-term threat from the south was not eliminated.

Russia needed a strategy in the west and one in the south. In the west, part of that strategy evolved in Ukraine, keeping it from being a threat without the use of major Russian force. A tacit agreement was reached with Washington: The United States would not arm Ukraine with significant offensive weapons, and Russia would not move major force into Ukraine beyond the insurgencies already in place. Neither Russia nor the U.S. wanted war. Each wanted a buffer zone. That is what emerged.

Another piece of the lost buffer became, so to speak, available. Belarus is about 400 miles from Moscow. Poland, to its west, is hostile to Russia and contains some American forces. This represents a significant threat to Russia, unless Belarus could be brought into the Russian fold. The elections in Belarus held this year created an opportunity. President Alexander Lukashenko, a long-time ruler and in many ways the last Brezhnevite, faced serious opposition. The Russians backed Lukashenko and have essentially preserved his position. In return, Lukashenko is locked out of any accommodation with the West that Russia disapproves of, and also must accommodate Russian military requirements. The Baltics are still a threat, but their terrain makes large-scale assaults eastward difficult. The Poles and Americans are blocked from increasing eastward power unless they initiate a conflict, which they won’t. If the Lukashenko regime survives, it represents a major improvement on Russia’s western border.

In the south, we have a messier situation. Azerbaijan and Armenia have long fought, at various levels of intensity, over Nagorno-Karabakh. Recently, Azerbaijan, with the support of Turkey, chose to launch a major attack on Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan has avoided a full-scale conflict there for 20 years. (The Four-Day War in 2016 does not constitute a full-scale conflict.) Its reasons for launching the attack now are obscure. Turkey’s desire for a successful conflict likely derives from economic problems, coupled with reversals in its Mediterranean policy and its inability to impose its will in Syria. It needed a victory somewhere, and aiding its ally in taking Nagorno-Karabakh made sense.

The matter is more complex, however. The Russians are allied with Armenia and ought not to have wanted their ally defeated. Moreover, Russia would not want Turkey to be a significant force in the Caucasus. It undoubtedly knew of Azerbaijan’s plans because its intelligence would have detected Azerbaijani movements, and because Azerbaijan could not afford to alienate its northern neighbor. So the idea that the Russians were unaware of the war plan borders on the impossible. Russia had to have tacitly accepted Azerbaijan’s plans.

The reason all this was possible is that, in the end, it was Russia that helped negotiate the end of the war and, far more important, agreed to send nearly 2,000 troops as peacekeepers to Nagorno-Karabakh for at least five years. Two thousand Russians in this region represent a decisive force. No one will engage them. This means that its ally, Armenia, now has Russian troops to its east, and Azerbaijan has Russian forces to its north and also in the west. Georgia now faces a similar situation. In effect, Russia has made a significant move to reclaim, or at least have a major element of control in, the South Caucasus. The presence of a major Russian force, with a long-term right to remain there, eliminates what had been a potential long-term threat. The presence of U.S. troops in Georgia might be a problem, but given the lack of U.S. offensive intentions, it is unlikely to be willing to invest major forces in the region. And a minor presence of U.S. trainers in Georgia is something Russia can live with.

Apart from Armenia, the great loser in this is Turkey, which was excluded from the peacekeeping force. Turkey saw Azerbaijan, an important ally in the region, accommodate Russia and accept its blocking of Turkish ambitions at a time when Turkey badly needed a win. In addition, this affair – accidentally or deliberately – coincided with the American presidential transition, a time when decision making in the U.S. is usually difficult, and this time near impossible. It is hard not to think that the Russians either took advantage of events or engineered them. In any case, their apparent successes in Belarus and now in the South Caucasus are major steps in Putin’s vow to reverse the strategic consequences of the fall of the Soviet Union without forging a single nation.

Strategic depth is vital in the very long term, and it’s importance is burned into Russia’s memory. But it has minimal significance now. The United States and NATO have no interest in invading Russia. While Russia must assume the worst, its immediate problem remains its economy and reliance on energy exports as a prime revenue source, without any control over pricing. Russia has executed a strategic coup, but it continues to experience the financial and internal political stresses on which we based our forecast. It has not solved its core problems by strategic maneuvers, however useful. Without a transformation of its economy, it continues to be in crisis.

No comments:

Post a Comment