By Duncan Bartlett

If India fights a war, it will do so armed with weapons it has bought from Russia, the United States, and Israel.

The country already has a formidable armory – including approximately 150 nuclear warheads – and this year, despite the recession caused by coronavirus, it has significantly raised the amount it spends on arms. Following a clash with China on the Himalayan border in June, which led to the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers, defense minister Rajnath Singh persuaded parliament to endorse an emergency budget.

However, the policy of a close convergence with the United States, based around defense, was evident long before the last border clash with China, or the COVID-19 pandemic.

When President Trump visited the Indian state of Gujarat at the invitation of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in February 2020, he addressed a huge and friendly crowd: “As we continue to build our defense cooperation, the United States looks forward to providing India with some of the best and most feared military equipment on the planet. We make the greatest weapons ever made: airplanes, missiles, rockets, ships. We make the best of it. And we’re dealing now with India.”

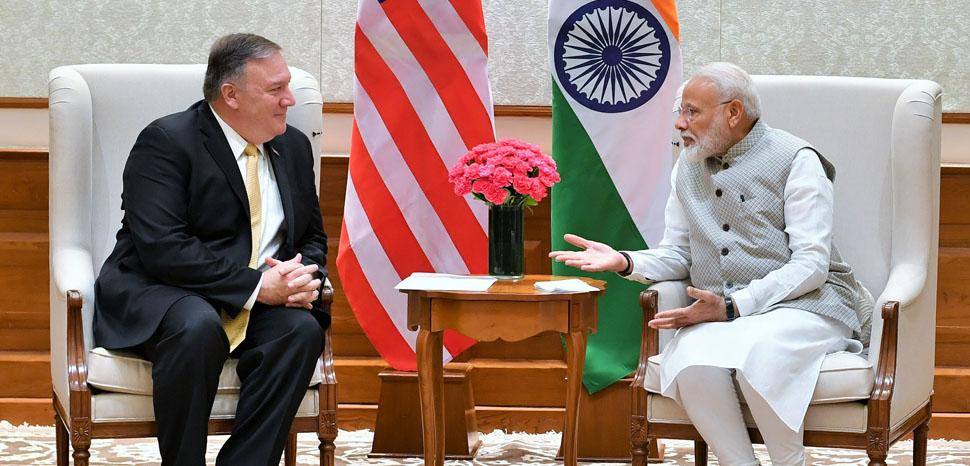

Just a week ahead of the November US presidential election, two of Trump’s closest aides carried his messages of support to India on a trip to New Delhi. Defense Secretary, Mark Esper, and Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, hailed what they described as a “significant milestone” as India and the United States signed the Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement, or BECA. The agreement enables the nations to share geospatial intelligence gathered from satellites and other sources.

Mr Esper also said that the US expects to increase arms sales to India, including fighter aircraft and unmanned aerial systems. The Trump administration wants the deals signed before the presidential election.

This all points to a stronger geopolitical alignment with India over the long term, regardless of who prevails in November.

At the same time, India is purchasing anti-tank guided missiles from Israel and fighter planes, drones, and air defense systems from Russia.

This led to what the Reuters news agency described as an “awkward moment” at a news conference in New Delhi involving Mr Esper and Defense Minister Singh. When he was asked whether India is prepared to stop buying Russian weapons, Mr Singh demurred: “Decisions happen on the basis of negotiations.”

Despite its pivot towards the United States, India is unwilling to sever its ties with Russia, with which it has a complex relationship. Traditionally, India attempted to follow a non-aligned approach in foreign policy, which it developed during the Cold War. This was influenced by its own strong sense of post-colonial independence, as well as a feeling of vulnerability in a bipolar world.

During the 1970s, as it built its nuclear arsenal, India was regarded as a rogue state by the United Nations, for violating the nuclear non-proliferation treaty. India insists it was never a signatory to the deal and needed to defend itself. Now, Mr Modi is seeking a great elevation in international status: a place at the top table of the United Nations.

In his address to the 75th General Assembly of the UN in September, Mr Modi reiterated his aspiration to gain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. He said it was justified considering India’s history, size, and economic potential.

The makeup of the security council, the P5, has remained unchanged since its inception in 1945. For India to join, all the members would need to invite it on board and agree to eject an existing member. Were it up to the United States, India would probably be offered a place. Russia would also value having India around the table. However, other P-5 members – namely France and the United Kingdom – will go to great ends to guard their own seats. And intense resistance to India joining the United Nations Security Council can also be expected from China.

The closer it gets to the US, the further India moves diplomatically from Beijing. Speaking to the Indian press in New Delhi, Secretary Pompeo said: “Today is a new opportunity for two great democracies like ours to grow closer,” urging the countries to confront the “Communist Party’s threats to security and freedom.”

Communist China’s strong support for Muslim Pakistan is a constant cause of frustration and alarm for India. China also holds considerable influence over most of India’s other neighbors, including Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

The US wants to use India as the key component of a coalition against China in what has been framed as its “Indo-Pacific” strategy. India is part of the Quad, an informal security alliance, also involving the US, Australia and Japan. Pompeo said he hopes the Quad will be formalized and enlarged, hinting that the United Kingdom and Canada may also join.

The populist-nationalist streak which brought Prime Minister Modi to power has often been likened to Trump’s approach. Both leaders are formidable campaigners, who promise national transformation and the restoration of traditional values. Prime Minister Modi won a landslide election last year.

Modi supporters tend to like Trump’s foreign policy priorities – especially the challenge to China. But away from the political meetings, the mood is more cautious. The International Monetary Fund predicts India’s economy will contract 10 percent in 2020, and not fully recover in 2021. China’s economy, by contrast, has already bounced back from the pandemic and is growing at around five percent. Despite Modi’s optimistic speeches about how India is a rival to China and could one day overtake it, Indians are much poorer than the Chinese and the economy is not about to catch up any time soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment