See Seng Tan

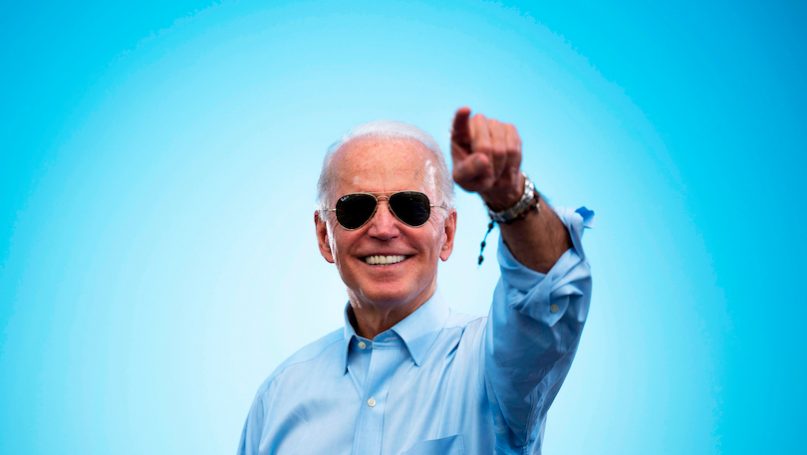

Joe Biden’s win in the 2020 US presidential election looks set to reverse the course taken by Trump and his “America First” platform over the past four years, which largely rejected multilateralism, downplayed alliances, took the fight to China, and abandoned America’s role in international leadership since the end of the Second World War. ‘Working cooperatively with other nations that share our values and goals does not make the United States a chump,’ as Biden argued in a 2020 essay for Foreign Affairs. ‘It makes us more secure and more successful. We amplify our own strength, extend our presence around the globe, and magnify our impact while sharing global responsibilities with willing partners’ (Biden, 2020).

America’s return to the international fold under a Biden administration will likely have key implications for multilateral cooperation in a host of global issues ranging from climate change, public health, trade, nuclear non-proliferation, human rights, to a rules-based international order (Patrick, 2020). But what might this anticipated return to multilateralism and international collaboration look like in the Asia-Pacific region, where China’s proprietary interests and influence loom large?

Where America’s initial re-engagement with international organizations and protocols goes, Biden will have his hands full working to restore his country’s standing and credibility with institutions, allies, partners, and friends alike. Almost any multilateral institution or global framework will do – so encompassing has Trump’s estranged relations with such been – but take for example the World Health Organization and the international climate-change pact, both from which, among others, Trump withdrew the United States. On his part, Biden has vowed to recommit his nation to those and other multilateral institutions and protocols.

The international response to Biden’s victory hitherto has been positive; the secretary-general of the United Nations recently hailed his organization’s partnership with the U.S. as an ‘essential pillar’ of world order (United Nations, 2020). Yet Biden’s claim that his foreign policy agenda ‘will place America back at the head of the table’ of those institutions and frameworks seems somewhat premature, even if U.S. leadership in those settings has been sorely missed (Biden, 2020).

Biden will find much of the Asia-Pacific amenable and welcoming of America, if only because regional angst over Trump’s hard-line stance against China has grown (Crabtree, 2020). For a region where impressions matter, Biden’s readiness to engage with his Asia-Pacific counterparts will make an immediate impact, especially since Trump skipped the region’s summits and key multilateral meetings over the past three years (Kuhn, 2020). According to a top advisor to Biden, as U.S. president, Biden ‘will show up and engage ASEAN [Association of Southeast Asian Nations] on critical issues’ (Strangio, 2020). Since the onset of the Obama administration’s ‘Asia pivot’ strategy, the region’s multilateral bodies like the ASEAN Regional Forum have become arenas where US-China histrionics over the South China Sea occasionally play out and little of substance is achieved.

On the other hand, the ADMM-Plus has demonstrated that Asia-Pacific militaries, including Chinese and U.S. forces, can successfully cooperate multilaterally in specific nontraditional security areas (Tan, 2020a). Whether Biden can work with Asia-Pacific partners to rejuvenate and strengthen those multilateral arrangements is an important question; here, one is reminded of past U.S. officials like Hillary Clinton who, not without exasperation, urged the need for Asia-Pacific institutions to go beyond just being talk-shops and ‘produce results’ (Tan, 2015: 121).

How Biden engages with China – with whom he has vowed to ‘get tough’ – will impact the quality and tenor of Asia-Pacific multilateralism. Biden’s stance on the South China Sea is unlikely to deviate from that of his predecessor. The Trump administration has conducted 20 or more freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea, of which nine took place in 2019 alone. While the pace and scope of a Biden administration’s participation in FONOPs in those waters remains to be determined, their intensity is unlikely to be diminished. Notably, Biden has avoided using the term ‘Indo-Pacific’ in his public remarks presumably to distance himself from the overtly anti-China slant of the Trump administration’s ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ strategy (Tan, 2020b). His willingness to listen to his Asia-Pacific counterparts could temper his security approach to the region and round the sharp edges of the Quad – the informal security forum comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the U.S. – which has been likened to an anti-China alliance (Quinn, 2020).

Furthermore, many believe America has fallen behind China in terms of their comparative influence in the region, seen by many as ‘ground zero’ in the conflict between those two major powers (Becker, 2020). America is neither a participant in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – of whose earlier incarnation, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, Trump backed the U.S. out – nor a member of the recently signed Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a massive trade deal spanning 15 countries and 2.2 billion people, nearly 30 percent of the world’s population, with a combined GDP of roughly $26 trillion or (based on 2019 data) nearly 28 percent of global trade (Tan, 2020c). Although China is not part of the CPTPP, it nonetheless is the fulcrum of the RCEP with an economy that dwarfs those of its fellow RCEP members.

Granted, America is no laggard despite its absence from those multilateral pacts; it does $2 trillion in trade with the RCEP countries – of which $354 billion was with the ASEAN region in 2019 alone. Yet that pales in comparison to China’s trade with the ASEAN region, which was $644 billion over the same year (Tan, 2020c). Isolated instances of debt traps caused by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) aside, the Asia-Pacific is arguably no passive recipient of Chinese largesse but an active shaper of the pace and scope of the BRI (Jones and Hameiri, 2020). Pursued smartly, America’s economic engagement with the region could regain it friends and produce significant dividends even if Washington cannot compete with Beijing’s checkbook diplomacy.

America’s anticipated return to cooperative multilateralism in the Asia-Pacific will be a welcome antidote to Trump’s highly transactional and fractious brand of international diplomacy. However, its success will very much depend on the quality of its ties with China as well as Washington’s ability to engage with regional partners on their terms.

No comments:

Post a Comment