MICHAEL SCHUMAN

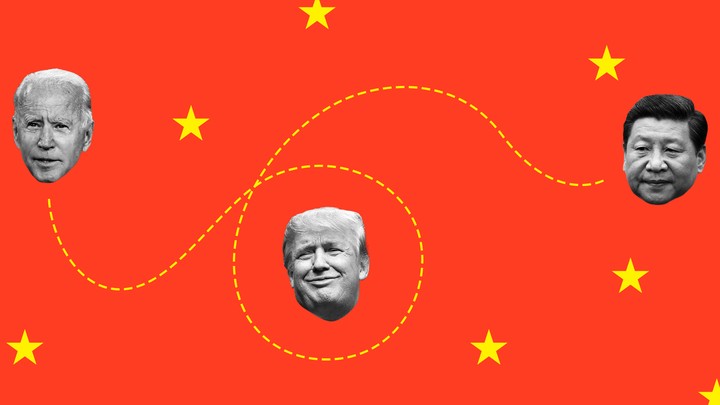

Like Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Adolf Hitler or George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, Chinese President Xi Jinping has just had an epic foreign-policy failure—he just doesn’t appear to have realized it yet.

Through four years of Donald Trump’s presidency, Xi had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to significantly, and perhaps permanently, expand Chinese influence around the world at America’s expense. By angering friend and foe alike, withdrawing from global institutions and agreements, and failing to tackle the coronavirus pandemic, Trump left the world ripe for a new leader to step into Washington’s worn shoes. Some were convinced this was China’s moment. “Sadly, the art of diplomacy has been lost in Washington D.C.,” the former Singaporean diplomat Kishore Mahbubani wrote earlier this year. “This has created a massive opening that China has taken full advantage of, on its way to victory over the post COVID-19 world.”

But Xi blew it. A recent Pew Research Center global survey revealed that attitudes toward China have drastically darkened in a number of countries, sinking to all-time lows in an array of nations such as Canada, Germany, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Xi himself didn’t fare any better. Though his image around the world is still a bit better than Trump’s, a median of 78 percent of respondents said they had little or no confidence that Xi would do the right thing in global affairs, a sharp spike from 61 percent in 2019. In almost all of the 14 countries included in the report, negative opinion of Xi reached the highest levels on record. With Joe Biden about to become the next U.S. president, Xi may have lost any chance of fixing his mistakes, and the consequences for China’s role in the world could be huge.

This disaster underscores how China’s political system is ill-suited for the role of global superpower. Beijing is undoubtedly more powerful than it was in January 2017, when Trump entered the Oval Office, yet what is perhaps not fully understood is how much stronger it could have been. Power is about more than simply military might, financial leverage, or economic size—it includes the exertion of a softer form of influence, whereby countries follow a hegemon’s example not because they are forced to, but because they want to. A pillar of Pax Americana has been the ideals it has traditionally promoted, including free speech and free trade, that appealed to other societies.

Xi is not unaware of the importance of “soft” power when it comes to global influence. He has called on the Chinese to market their own traditions and values around the world as a way of building the country’s international stature. Historically, cultural bonds were crucial to sustaining Chinese dominance in East Asia. Yet China has more recently defaulted largely to coercing rather than coaxing, imposing its terms abroad, and leaving a bitter taste for those who are forced to agree to Beijing’s demands.

The problem is that China’s leadership is too consumed by domestic concerns, and too insecure in its standing at home and abroad, to allow its diplomats to do their jobs with the deftness and flexibility to exploit opportunities. That means China will struggle to take over the role the United States has played in the world for the past seven decades.

Of course, they’ve tried. China now sits at the center of a substantial Asian trade bloc with the completion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, filling space emptied when Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a pact that would have solidified the American economic presence in Asia. Chinese leaders have attempted to capitalize on the coronavirus pandemic to promote themselves as more responsible global citizens. The state’s propaganda machine relentlessly mocked Trump for his inept response to the outbreak and touted Beijing’s own virus-fighting success as evidence that its governance system was a superior model for the world. While Trump pulled the U.S. out of the World Health Organization, Xi joined its program to provide a vaccine to poor nations.

Overall, this marketing effort has failed. In the Pew survey, a median of 61 percent of respondents thought China did a bad job handling the virus. But more important, whatever good Beijing did was reversed by its belligerence in other diplomatic disputes. After a nasty June brawl along the contested China-India border left 20 Indian soldiers dead, New Delhi responded by banning WeChat, TikTok, and other Chinese tech services, while the Indian public staged anti-China protests and boycotts of Chinese products. The U.K. was furious over a national-security law Beijing imposed on Hong Kong this summer to squash the city’s prodemocracy movement. Boris Johnson’s government believes the law violates a treaty the two countries signed regulating the former British colony’s handover to Chinese authority. And in disagreements with Canada and Australia, the Chinese government has blocked imports and effectively taken their nationals in China hostage. Michael Kovrig, a former Canadian diplomat, has been locked up in China for more than 700 days in retaliation for Ottawa’s arrest of a Huawei executive at Washington’s request on allegations of fraud. The Chinese even managed to anger more sympathetic African countries when Africans living in China faced severe discrimination during the coronavirus outbreak.

Often, Chinese diplomats and state media hurl insults and threats at their critics. In August, when a Czech politician led a delegation to Taiwan, which Beijing still claims as a runaway province, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi warned that his government “will make him pay a heavy price for his short-sighted behavior and political opportunism,” a threat that received a sharp rebuke from the Czechs, and even a protest from usually mild-mannered Germany. Hua Chunying, spokesperson for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, once tweeted that Washington’s campaign to contain China “is as futile as an ant trying to shake a tree.” The Global Times, a Communist Party–run newspaper, warned that Australia “risks becoming the ‘poor white trash of Asia’” by curtailing economic ties with China, while its editor called the country “chewing gum stuck on the sole of China’s shoes.” (It will come as little surprise, then, that Australians’ opinion of China has turned starkly negative. In the Pew survey, 81 percent held an unfavorable view of China, up from 57 percent the year before.)

It may seem bewildering that the leadership in Beijing, which so badly desires international respect and acclaim, would pursue a foreign policy so obviously not winning friends and influencing people—and even more baffling that it persists in that policy despite its many missteps.

The only way to understand this behavior is through a Chinese lens. Beijing’s aggressive foreign policy is an outgrowth of the government’s insecurity and confidence. On one hand, the Communist Party is always mindful of its standing at home. There, its propaganda has crafted a narrative of China as a victim of foreign predation whose time has come to stand tall once again on the world stage (under the firm guidance of the party). That almost requires Beijing to take a hard stance in foreign disputes—anything less might be perceived as unacceptable weakness. On the other hand, China’s growing economic clout has convinced Beijing policy makers that they possess the power to assert their will over other countries.

“Ultimately, the Chinese care first and foremost about stability and legitimacy at home, and they seem to be confident enough about China’s growing capabilities and its ability to influence the policies of other nations, in part through imposing fear of retribution,” Bonnie Glaser, the director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, explained to me. “They just believe that over time … countries will accommodate China and show deference to China.”

So far, though, China’s policy is achieving the opposite: not merely alienating foreign governments, but possibly driving them together. For instance, a loose partnership known as “the Quad,” comprising four countries with grievances toward and concerns about China—Australia, India, Japan, and the United States—could be coalescing into a more formal anti-China bloc in Asia. The foreign ministers of the four nations met in Tokyo in early October and China was a topic of discussion, especially with firebrand U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo in the room. Such budding coalitions ring alarm bells in Beijing. “China still believes that under most circumstances, it can divide and conquer,” Glaser added, “but it does have some concern today of the potential for countries to come together to work against China.”

Still, Beijing doesn’t appear concerned enough to do much about it. There are few signs that Beijing is reassessing its foreign policy. To commemorate the 70th anniversary of China’s entry into the Korean War in late October, Xi chose to deliver a fiery, nationalistic address. “Seventy years ago, imperialist invaders brought the flames of war burning to the doorway of the new China,” he said. “The Chinese people have a deep understanding that in responding to invaders, one must speak to them in a language that they understand.”

Even if Xi changes course, it may be too late. A well-known and well-liked president in Biden is likely to repair relations with America’s traditional allies in Europe and Asia, and even worse from Beijing’s perspective, he has already pledged to forge an international coalition to take on China. He also intends to reengage with the world in ways that could close off space for China, promising to rejoin the WHO and the Paris climate accord. “When I’m speaking to foreign leaders, I’m telling them: America is going to be back,” Biden tweeted after his election. “We’re going to be back in the game.”

And an unpopular Xi and his band of angry diplomats have left the world wide open for America’s return.

No comments:

Post a Comment