Niall Ferguson

A little French word that used to play a big role in global politics is poised for a comeback: detente. The word was first used as a diplomatic term in the early 1900s, for example when the French ambassador in Berlin attempted — in vain as it proved — to improve his country’s strained relationship with the German Reich, or when British diplomats attempted the same thing in 1912. But detente became familiar to Americans in the late 1960s and 1970s, when it was used to describe a thawing in the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

I have argued since last year that the U.S. and the People’s Republic of China are already embroiled in Cold War II. President Donald Trump did not start that war. Rather, his election represented a belated American reaction to a Chinese challenge — economic, strategic and ideological — that had been growing since Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in 2012.

Now, Joe Biden’s victory in the U.S. presidential election (the various legal challenges to which will achieve nothing other than to salve Trump’s huge but hurt ego) creates an opportunity to go from confrontation to detente much sooner than was possible in Cold War I.

The Chinese government waited until Friday before offering Biden congratulations on his victory. Put that down to caution. As during the election campaign, Xi and his advisers have been striving not to provoke Trump, for whom they have come to feel a mixture of contempt and fear. But a few unofficial voices have ventured to express what Xi doubtless thinks. Wang Huiyao, the president of the Beijing-based Center for China and Globalization, said last week that he hoped a Biden administration would “provide China and the U.S. … with more dialogue and cooperation channels concerning energy saving and emission reduction, economic and trade cooperation, epidemic prevention and control.” Speaking at the same event, the former foreign vice-minister He Yafei talked in similar terms.

Such language might be expected to a ring a bell with the Democratic Party’s throng of foreign policy experts, who have spent the past four years — from the Brookings Institution to the Aspen Strategy Group to Harvard’s Kennedy School — bemoaning Trump’s assault on their beloved liberal international order.

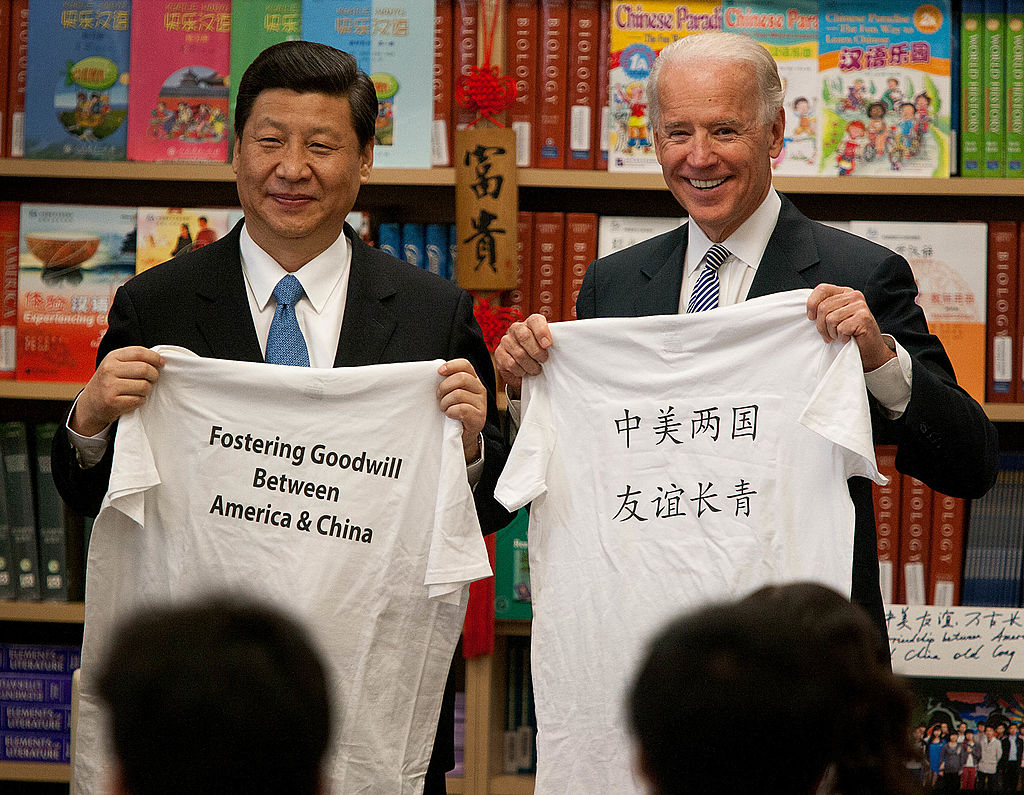

It seems pretty clear that Biden himself would gladly return to the days of the Barack Obama administration, when his meetings with Xi, Premier Li Keqiang and other Chinese leaders were all about the “win-win partnership” that I used to call “Chimerica.” Eight years ago, he was pictured beside Xi holding up a T-shirt with the slogan “Fostering Goodwill Between America & China.”

Asked about superpower competition at an event in Iowa in 2019, Biden replied: “China is going to eat our lunch? Come on, man. They can’t even figure out how to deal with the fact that they have this great division between the China Sea and the mountains in the East, I mean the West. They can’t figure out how they’re going to deal with the corruption in the system. I mean, you know, they’re not bad folks, folks. But guess what? They’re not competition for us.”

Luckily for Biden, he had few opportunities to say more in this nonsensical vein, as this year’s election campaign — including both presidential debates — scarcely touched on foreign policy, depriving Trump of the opportunity to point out how much more in touch he is with public sentiment, which has grown increasingly hostile to China since Biden left office four years ago.

Detente should not be confused with amity. Whatever comes of the diplomacy of the new presidency, it is unlikely to be a new era of Sino-American friendship. Detente means reducing the tensions inherent in a cold war and reducing the risk of its becoming a hot one.

“The United States and the Soviet Union are ideological rivals,” wrote Henry Kissinger, who was in many ways the architect of detente in the 1970s. “Detente cannot change that. The nuclear age compels us to coexist. Rhetorical crusades cannot change that, either.”

For Kissinger, detente was a middle way between the appeasement that he believed had led to World War II, “when the democracies failed to understand the designs of a totalitarian aggressor,” and the aggression that had led to World War I, “when Europe, despite the existence of a military balance, drifted into a war no one wanted and a catastrophe that no one could have imagined.”

Detente, Kissinger wrote in his memoir, “The White House Years” — published in 1979, 10 years before the effective end of the first Cold War — meant embracing “both deterrence and coexistence, both containment and an effort to relax tensions.”

Today, it is the U.S. and China who find themselves — as Kissinger observed in an interview with me in Beijing last year — “in the foothills of a Cold War.” As I said, this Cold War was not started by Trump. It grew out of China’s ambition, under Xi’s leadership, to achieve something like parity with the U.S. not only in economics but also in great-power politics. The only surprising thing about Cold War II is that it took Americans so long to realize that they were in it. Even more surprising, it took a maverick real estate developer turned reality TV star turned populist demagogue to waken them up to the magnitude of the Chinese challenge.

When Trump first threatened to impose tariffs on Chinese goods in the 2016 election campaign, the foreign policy establishment scoffed. They no longer scoff. Not only has American public sentiment toward China become markedly more hawkish since 2017. China is one of few subjects these days about which there is also a genuine bipartisan consensus within the country’s political elite.

Unlike the president-elect himself, the members of Biden’s incoming national security team have spent the past four years toughening up their stance on China. In Foreign Affairsthis summer, Michele Flournoy, the favorite to become secretary of defense in the new administration, argued that “if the U.S. military had the capability to credibly threaten to sink all of China’s military vessels, submarines and merchant ships in the South China Sea within 72 hours, Chinese leaders might think twice before, say, launching a blockade or invasion of Taiwan.”

Flournoy wants the Pentagon to invest more in cyberwarfare, hypersonic missiles, robotics and drones — arguments indistinguishable from those put forward by Christian Brose, a top adviser to the late Senator John McCain, in his book “The Kill Chain.”

Biden’s key Asia advisors, Ely Ratner and Kurt Campbell, have also acknowledged that the Obama administration, like its predecessors, underestimated the global ambition of China’s leaders and their resolve to resist political liberalization. Last year, Campbell and Jake Sullivan (who was Vice President Biden’s national security adviser in 2013-14), made what seemed like an explicit argument for detente in Kissinger’s sense of the term. “Despite the many divides between the two countries,” they wrote, “each will need to be prepared to live with the other as a major power.”

U.S. policy toward China should combine “elements of competition and cooperation” rather than pursuing “competition for competition’s sake,” which could lead to a “dangerous cycle of confrontation.” Campbell and Sullivan may insist that Cold War analogies are inappropriate, but what they are proposing comes straight out of Kissinger’s 1970s playbook.

Yet the lesson of detente is surely that a superpower ruled by a Communist Party does not regard peaceful coexistence as an end in itself. Rather, the Soviet Union negotiated the 1972 Strategic Arms Limitation Talks agreement with the U.S. for tactical reasons, without deviating from its long-term aims of achieving nuclear superiority and supporting pro-Soviet forces opportunistically throughout the Third World.

The crucial leverage that forced Moscow to pursue detente was the U.S. opening to China in February 1972, when Nixon and Kissinger flew to Beijing to lay the foundations of what, 30 years later, had grown into Chimerica. Yet the compulsive revolutionary Mao Zedong was never entirely at ease with his own opening to America. At one point in late 1973, when the U.S. offered China the shelter of its nuclear umbrella from a possible Soviet attack, Mao became indignant and accused Premier Zhou Enlai of having forgotten “about the principle of preventing ‘rightism.’”

For all its achievements, detente came to be a pejorative term in the U.S., too. It is often forgotten how much of Ronald Reagan’s rise as the standard-bearer of the Republican right was based on his argument that detente was a “one-way street that the Soviet Union has used to pursue its aims.”

The danger of detente 2.0 is that Biden will be Jimmy Carter 2.0. Throughout his four years in the White House, Carter was torn between the “progressive” left wing of his own party and hawkish national security advisers. He ended up being humiliated when the Soviet Union tore up detente by invading Afghanistan.

Consider how China will approach the new administration. Beijing would like nothing more than an end to both the trade war and the tech war that the Trump administration has waged. In particular, Beijing wants to get rid of the measures introduced by the U.S. Commerce Department in September, which effectively cut off Huawei and other Chinese firms from the high-end semiconductors manufactured not only by U.S. companies but also by European and Asian companies that use U.S. technology or intellectual property.

In the tech war, Team Biden seems ready to make concessions. Some of the president-elect’s advisers want to offer wider exemptions for the foreign chipmakers who supply Huawei and to drop Trump’s executive actions against the Chinese internet companies TikTok and Tencent. But in return for what? Is China about to halt its dismantling of what remains of Hong Kong’s semi-autonomy? Clearly not. Is China going to suspend its policies of incarceration and re-education of Uighurs in Xinjiang? Not a chance. Will China stop exporting its surveillance technology to any authoritarian government that wants to buy it? Dream on.

If China’s quid pro quo is nothing more than Xi’s recent commitment to be “carbon neutral” by the distant year 2060, then the Biden administration would be nuts to do detente. China is currently building coal-burning power stations with a capacity of 250 gigawatts, more than this country’s total coal-fueled power capacity. The country accounts for roughly half of all the new CO2 emissions since the Paris Agreement on climate change was signed. If Biden is determined to take the U.S. back into the Paris accord, he needs to say explicitly that it will soon be a dead letter without meaningful Chinese actions.

The microchip race is a bit like the nuclear arms race in Kissinger’s time. Beijing lags behind qualitatively, as the Soviet Union did, though it can win in terms of quantity. China cannot yet match the sophistication of the chips made by Taiwan’s TSMC.

Its goal is to buy time while catching up and achieving “technological self-reliance.” The obvious U.S. response is to try to stay ahead. Biden (who is going to need all the bipartisan issues he can find if Republicans retain control of the Senate) may well work with the GOP to pass the CHIPS Act, which aims to promote domestic semiconductor production.

Such technological races can go on for years. Similar races are underway in the fields of artificial intelligence, digital currency and even Covid vaccines. But the lesson of Cold War I is that the ultimate test of any national security policy is its first crisis. In 2021 there is a significant chance that North Korea will provide the Biden administration with its earliest foreign-policy challenge in the form of new missile or nuclear tests. But there is another scenario: a Taiwan crisis.

Biden should have no illusions about Xi. The Chinese leader’s ultimate goal is to bring to an end Taiwan’s de facto autonomy and democracy and bring it fully under Beijing’s control. This is not just about asserting the principle of “One China, One System.” There is the eminently practical argument that China would no longer need play catch-up in the chip race if it directly controlled Taiwan. Earlier this year, one nationalist blogger proposed a simple solution: “Reunification of the two sides, take TSMC!”

Meanwhile, as we have seen, there has been a bipartisan upgrade of the U.S. commitment to Taiwan, which dates back to the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act. Not long after Flournoy’s pledge to increase America’s capacity to deter Beijing from invading the island, Richard Haass of the Council on Foreign Relations argued for an end to the “ambiguity” of the U.S. commitment to defend Taiwan. “Waiting for China to make a move on Taiwan before deciding whether to intervene,” he wrote in September, “is a recipe for disaster.” But another recipe for disaster would be a showdown over Taiwan before a Biden administration has even begun beefing up deterrence.

Relations between Washington and Beijing reached an impasse this year. Strategic dialogue gave way to Twitter abuse. Detente 2.0 would be an improvement, if only at the level of superpower communication.

The rationale for detente, as Kissinger often argued in the 1970s, was the world’s growing interdependence. That argument has even more force today. The pandemic has revealed the immense extent of our interdependence and the impossibility of a world order based on — to use French again — sauve qui peut (“every man for himself”) and chacun a son gout (“to each his own”).

A novel virus in Wuhan has caused a global plague and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans. Similar interdependence will be revealed if global warming has the dire consequences projected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Economically, too, the U.S. and China remain interdependent. Trump’s tariffs did nothing whatever to reduce the bilateral trade deficit.

Yes, the U.S. and China are in the foothills of a Cold War. But there is no good reason to go through decades of brinkmanship before entering the detente phase of this cold war. Let Taiwan in 2021 not be Cuba in 1962, with semiconductors playing the role of missiles.

Nevertheless, as in Kissinger’s time, detente cannot mean that the U.S. gives China something for nothing. If the incoming Biden administration makes that mistake, the heirs of Ronald Reagan in the Republican Party will not be slow to remind them that detente — diplomatic French for “let’s not fight” — was once a dirty word in American English.

No comments:

Post a Comment