By Phillip Orchard

For the past several years, China has been going to exaggerated lengths to isolate Taiwan – diplomatically, militarily, even epidemiologically. But Taipei and Washington have been finding some subtle but pointed ways to make clear that the self-ruled island is not exactly alone. There was, for example, the photo Taipei released earlier this month of President Tsai Ing-wen and her Cabinet walking down a hallway at an early warning radar site, with a U.S. military technical officer lurking in the background. In August, there was the U.S.-released photo of a bunch of Taiwanese airmen and, conspicuously, a handful of U.S. avionics advisers, posing in front of a Patriot missile battery in Taiwan. Also in August, there was the first-ever visit by Taiwanese troops to the de facto U.S. embassy in Taipei, where Washington has openly discussed stationing troops.

Taiwan and the U.S. have little reason to play coy about traditional means of U.S. support for the self-ruled island. The U.S. is required by U.S. law to sell Taiwan the arms it needs to defend itself, and it doesn’t typically do so covertly. Such arms packages have been getting larger and more frequent over the past couple of years, as have appearances by U.S. warships in the Taiwan Strait. And Washington, which doesn’t have official diplomatic ties with the government in Taipei, has also become less and less inclined to keep playing its game of diplomatic make-believe around Taiwan to please China, as illustrated by a pair of recent senior-level visits by U.S. officials. Still, there’s a world of difference between providing material and diplomatic support for Taiwan and putting U.S. forces in Taiwan.

So are Taipei and Washington signaling that a return of U.S. boots on the ground in Taiwan is on the table? Probably not in a major way. But Taiwan hosting at least a modest U.S. military presence in the not-so-distant future shouldn’t be ruled out.

Foot in the Door

For nearly a quarter century beginning in 1954, Taiwan hosted as many as 30,000 U.S. troops as the U.S. sought to deter the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) from attempting to put a decisive end to the Chinese civil war (and to discourage Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang from launching its own mainland invasion). But the U.S. committed to withdrawing all its forces from the island in its breakthrough 1972 joint communique with Beijing, and all were gone by the time the U.S. switched diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing in 1979.

Since then, like the State Department and every other U.S. government agency with an interest in Taiwan, U.S. military engagement in Taiwan has largely had to rely on unofficial or civilian workarounds. When Taipei in August opened a “U.S.-backed” F-16 maintenance center in the western Taiwanese city of Taichung, for example, technically it was done in partnership with Lockheed Martin Corp., not the U.S. military itself. Otherwise, U.S. forces have generally steered well clear of the island in the interest of managing latent tensions with Beijing – or so it was thought until the past couple of years.

In 2018, the U.S. State Department stirred up a minor cross-strait kerfuffle by requesting a routine deployment of U.S. Marines to provide security for the American Institute in Taiwan, the de facto U.S. embassy in Taipei. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis reportedly decided against the move after talks with Beijing. But last year, an institute spokesperson said that, actually, active U.S. military personnel have been stationed there since 2005 – and not just Marines but personnel from the Army, Navy and Air Force as well.

Also in 2018, the U.S. National Defense Authorization Act authorized port calls by U.S. Navy ships, and the Navy followed through shortly thereafter by dispatching a research vessel to the island. Meanwhile, there’s been a marked increase in discussion in U.S. and Taiwanese defense policy circles, and even the Taiwanese parliament, about a return of more substantial U.S. forces to Taiwan. There’s little evidence that any formal discussions on the matter have taken place. Still, the rumors have sparked no small amount of consternation in Chinese state media, with the Global Times warning that such a move would trigger “reunification by force.”

Why Taipei Might Be Interested

The increase in chatter about U.S. troops returning to Taiwan makes sense. Chinese military pressure on Taiwan has surged over the past year or so. The PLA isn’t capable of launching an amphibious invasion of Taiwan yet – at least not at an acceptable cost. But the PLA’s breakneck buildup of naval, air and missile capabilities is rapidly turning the cross-strait balance of power in the mainland’s favor. And while Taiwan has enormous geographical advantages working in its favor, there’s growing concern in Taipei about just how optimized the military is for deterring an invasion given the growth in Chinese anti-access/area-denial firepower, much less countering a Chinese blockade or, say, a seizure of one of Taiwan’s outlying islands.

The Communist Party of China, moreover, has a political imperative to reunify on its terms. Thus, China must make Taipei think reunification – whether peacefully or by force – is a matter of when, not if. Toward this end, China also needs to sow extreme doubt in Taipei about the United States’ willingness to intervene on its behalf – something that would expose U.S. forces to substantial losses.

From Taipei’s perspective, U.S. arms sales may not be enough to keep China at bay indefinitely. Taiwan doesn’t have the budgetary capacity to build or acquire the level of firepower the U.S. could bring to bear. And since the U.S. is leery of handing over its most sophisticated weapons and surveillance systems to a government so vulnerable to Chinese espionage and potentially capture, Taiwan is at increasing risk of losing what’s left of its technological superiority over the PLA. Thus, bringing back U.S. troops and U.S.-controlled assets could reasonably be considered a fine way to preserve the cross-strait status quo.

Realistic Possibilities

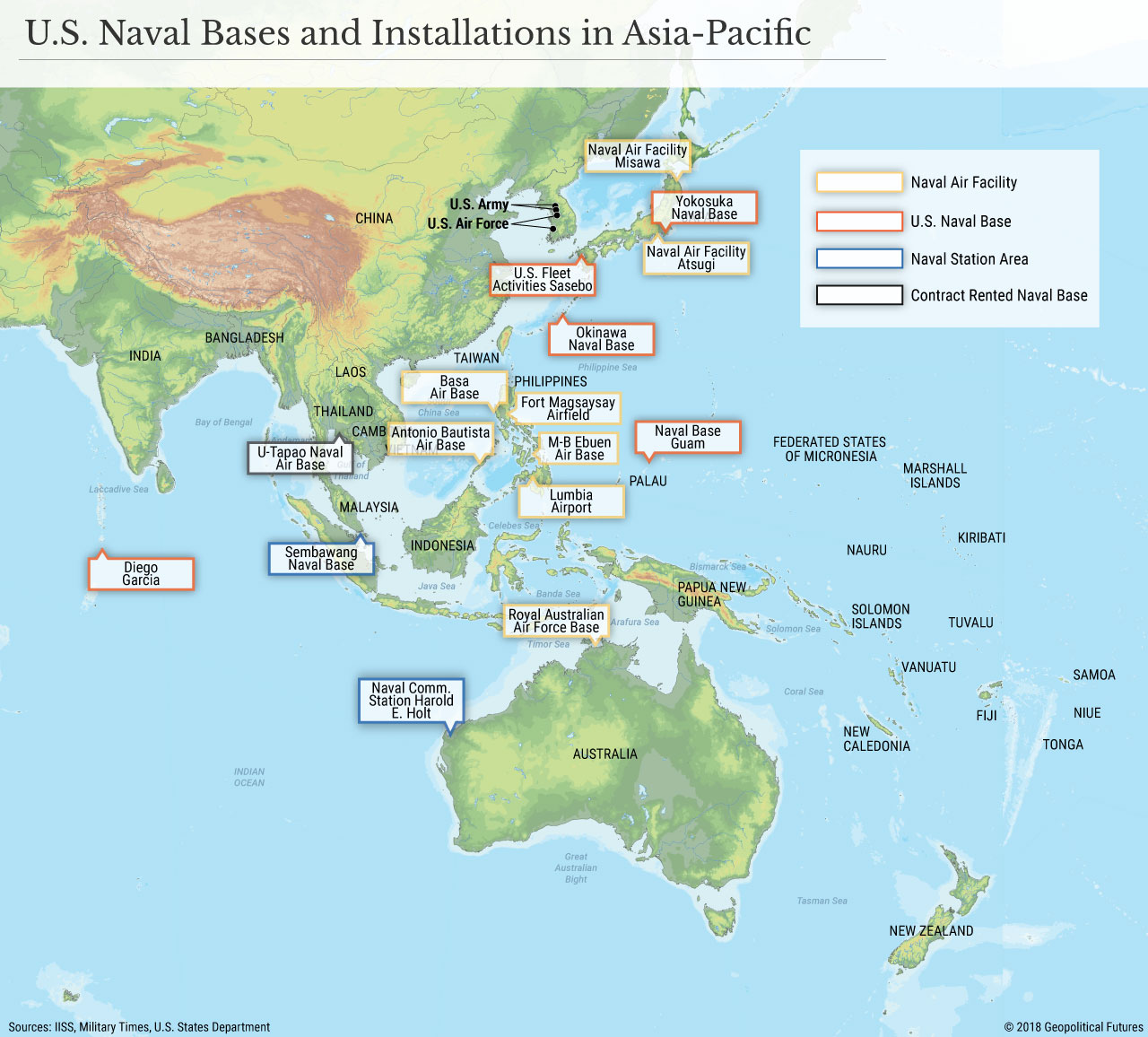

For the U.S., Taiwan’s geographic position offers innumerable advantages. Strategically, so long as the U.S. can pair its superior naval and aerial capabilities with bases and allied support along what’s known as the first island chain – Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia – it poses a threat to block sea lanes that are critical to China’s export-dependent economy. And more than any other island in this chain, Taiwan could be used by a foreign power to threaten the Chinese mainland itself. Since, with the U.S. basing agreement with the Philippines still stalled, the only existing major U.S. bases in the Western Pacific are thousands of miles away in Japan, South Korea and Guam, Taiwan could ostensibly also facilitate a more active U.S. presence in the South China Sea. More broadly, given China’s expanding arsenal of sophisticated precision-guided anti-ship missiles, the U.S. is keen to adopt a more distributed force posture in the region. The more places from which it can station and dispatch forces, the better.

In truth, the U.S. probably isn’t interested in basing large numbers of troops, warplanes and warships in Taiwan. The geographic benefits provided by the island probably are outweighed by the risks of putting U.S. forces so close to Chinese firepower. The U.S. can also exploit its main point of leverage over China – its ability to cut off chokepoints along the first island chain and egresses into the Indian Ocean like the Strait of Malacca – without Taiwan.

Still, establishing at least a modest military footprint in Taiwan could serve U.S. interests in a couple of key ways. One is by countering China’s creeping superiority in regional information operations (i.e., its communications, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities – the main benefit of its island bases in the Spratlys and Paracels). Another is by aiding the U.S. search for land-based missile sites in the Western Pacific. The U.S. is very keen to deploy land-based, intermediate-range cruise and ballistic missiles to the region to avoid being fully dependent on overstretched U.S. warships, which inherently carry limited magazines and would be difficult to resupply during combat. But the U.S. has had a devil of a time finding anyone willing to host such missiles. U.S. missiles in Taiwan would have the range to reach certain flashpoints in the East and South China seas, to say nothing of ports, airfields and anti-ship missile sites on the mainland itself.

Second, the U.S., of course, also has a strong interest in making it excessively risky for China to make a move on Taiwan – and thus incentivize Beijing to be content with less aggressive ways to meet its own strategic and political needs. It wouldn’t take a huge U.S. force to raise such costs. Even the presence of a relatively small number of U.S. military personnel at Taiwanese bases, radar sites and so forth would function as a tripwire and make it abundantly clear to Beijing that an attack on Taiwan – and thus on U.S. personnel – would very likely lead to war with the United States. Indeed, this may have been the intent behind the release of the photos of U.S. personnel at Taiwanese radar and anti-missile sites, which would be the initial targets in a Chinese “shock and awe” attack aimed at forcing Taipei to the negotiating table.

The political and diplomatic risks of such a move, though, are real and may quite likely be intolerable to Taipei and/or Washington. Despite the recent surge in tension with Beijing, both Washington and Taipei have every interest in avoiding backing China into a corner and in keeping a lid on the potential for conflict. So for now, think of any move dangling the possibility of a return of U.S. forces to Taiwan as merely a play for leverage – something intended to make clear to Beijing that its continued coercion could backfire. But if the two sides conclude that Beijing’s strategic and political imperatives make conflict inevitable, and that the best way to preserve the cross-strait status quo is to make an attempt at forceful reunification too risky for Beijing to stomach, then things might just get interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment