By Ekaterina Zolotova

On Sept. 23, Alexander Lukashenko officially took office as president of Belarus again. It wasn’t your typical inauguration ceremony, the date of which was kept secret until recently and which was attended by only 700 or so government officials. Anti-government protesters, already upset about what they consider a sham election, are even angrier. Protests this Sunday are expected to be even larger than the previous Sunday’s, which boasted 100,000 people.

It’s unclear how exactly this will shake out. On the one hand, Lukashenko hasn’t completely cracked down on the protests, and efforts to do so may fail. On the other hand, the opposition has yet to overwhelm the president – either through labor strikes or by crippling the government. No matter what happens, the Belarusian people will have to count on the good graces of Russia – which is exactly what Russia wants. That’s because neither the inauguration nor protests have solved Belarus’ problems. Lukashenko may stay, or he may go, but either outcome will be inclined to maintain good ties with Moscow.

Another Lukashenko term certainly means that he will continue relations with Russia. Relations between Minsk and Moscow are periodically overshadowed by trade and economic disputes, but Lukashenko has rarely strayed too far outside Russia’s orbit. Similarly, if Moscow had a choice, it would choose Lukashenko; the Kremlin already understands how to deal with him and how to leverage him.

For now, Moscow can sit tight because Lukashenko has a lot going for him. In contested elections such as these generally, the power lies in who can retain control over the economy, especially over the state sectors of the economy. And in the case of Belarus, Lukashenko still holds that power. The government also controls the education and health care systems, the media and the state budget. Despite some recent strikes and subsequent layoffs, the economy is largely unaffected, and enterprises continue to operate. The military supports Lukashenko too. During his inauguration, representatives of every branch swore an oath of loyalty to the president.

The political elite haven’t yet abandoned Lukashenko, nor has the opposition credibly threatened his control. All in all, he is confident that he still has the support of Russia, which has already provided a loan worth $1.5 billion and has promised to intervene in the event of an external threat. (The Kremlin would prefer to avoid this, if possible.)

Of course, Lukashenko cannot be called an undisputed electoral winner. The opposition may not yet be formidable enough to take him down, but it continues to coordinate its efforts in contesting the results of the election. Every Sunday, the protests against him grow larger, and every “dissident” he locks up will only add fuel to the fire. Discontent among the working population is growing as employees organize more strikes, and various opposition blocs say they are ready to unite.

Yet, Moscow can still rest easy. The opposition parties advocating new elections have already acknowledged that they will maintain dialogue and ties with Russia if they gain power. Moscow has been careful to (officially) distance itself from the events in Belarus so that it doesn’t alienate itself from any side. The government was quick to note, for example, that Russian representatives were not invited to the inauguration (nor even knew about it).

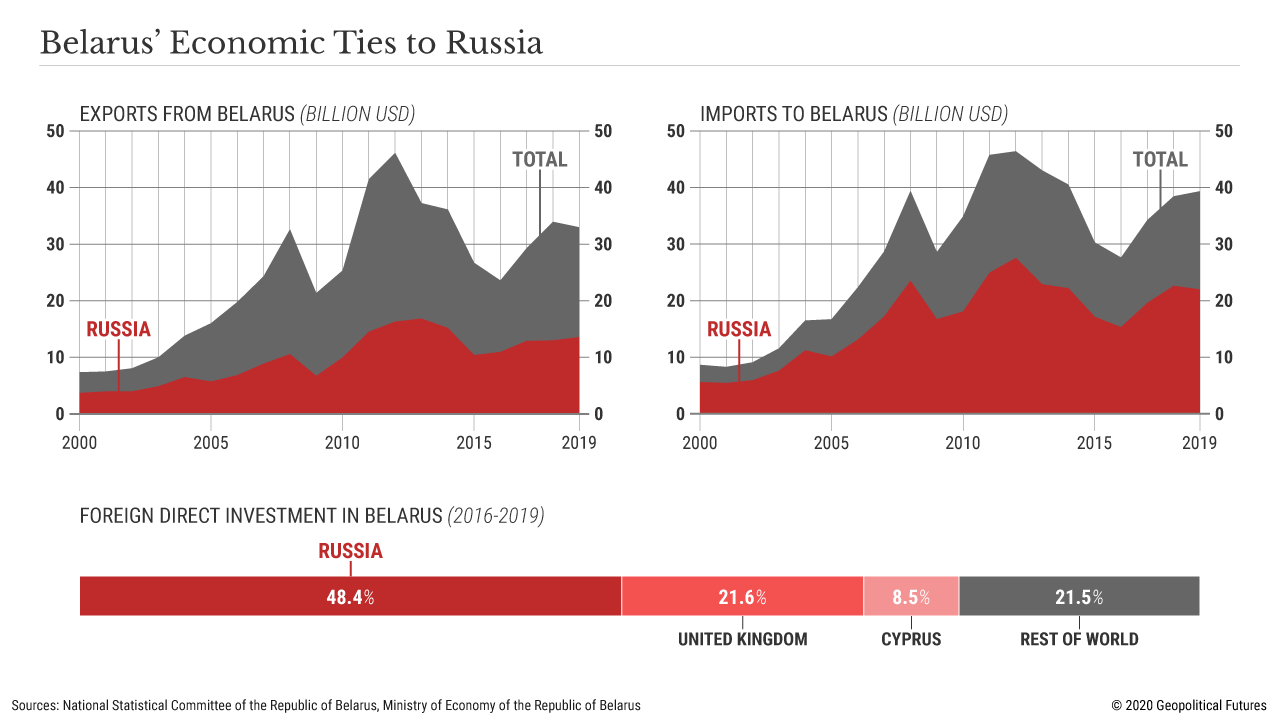

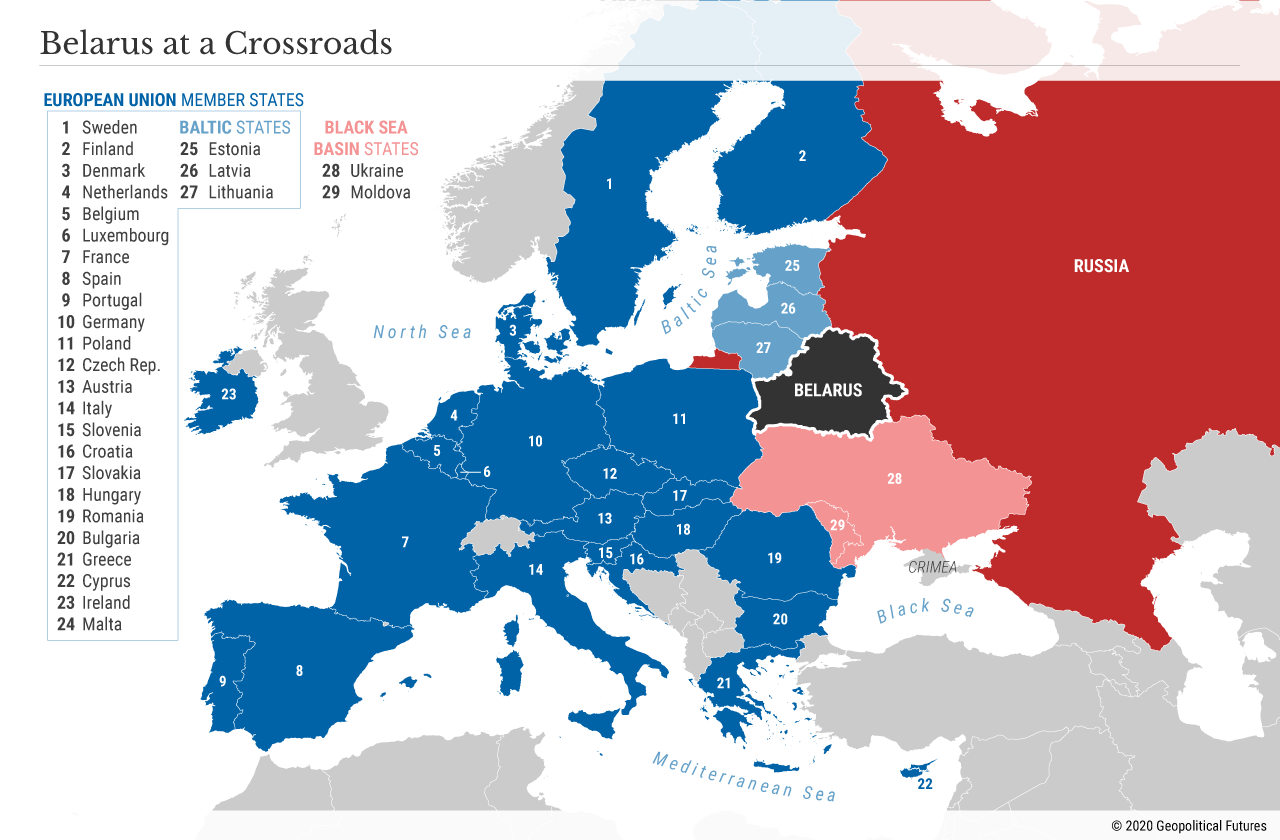

The Kremlin understands there is no need to attract additional attention to itself by appearing to act in bad faith when whoever wins will want to stay close to Moscow anyway. Belarus is too economically dependent not to. Nearly half of all Belarusian trade is with Russia, and Russia accounts for about 40 percent of all investment in Belarus. Many of the protesters may disapprove of Union State projects, which look to integrate Russia and Belarus, but they know Moscow has the power to dictate the pace of the negotiations. They are generally silent on the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union and the Collective Security Treaty Organization.

And aside from Russia, they have minimal external backing besides moral support. The United States, European Union and Canada refused to recognize Lukashenko but have chosen not to interfere. The EU is divided on the issue despite attempts by Poland and Lithuania to bring attention to it – in no small part by supporting the political opposition and trying to persuade other member states to apply sanctions. (There was only so much they could ever do. With the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, no one has all that much incentive to try, and besides, Belarus is too important to Russia as a buffer state to let acts of perceived aggression go unanswered.) The EU may not want Lukashenko in power, but between an economic crisis, a second wave of the pandemic and revitalized immigration issues, Brussels has much more pressing matters to deal with. Even if it did levy sanctions, Belarus has been under them so many times that it knows how to withstand them. For Brussels, sanctions are an easy, low-cost fix to let Russia and Belarus know the EU disapproves of the current government but not enough to provoke a major conflict.

The first episode in the drama that is Belarus ends inconclusively. Poland and Lithuania could not achieve what they wanted, the EU wasn’t in a hurry to impose sanctions, and the U.S. ignored it to the extent it could, worried as it is about its own elections. The protesters will continue to protest, and the opposition will continue to oppose. But among all this confusion, the only one who is definitely confident in its future is Russia.

No comments:

Post a Comment