by Warfare History Network

In late 1979, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was torn apart by a civil war pitting the weak Communist government of Hafizullah Amin against several moderate and fundamentalist Muslim rebel armies. The war had been brought about by Amin’s incompetence and corruption, his vicious program of political repression, the massacre of entire village populations, and a ham-handed agrarian “reform” program that disenfranchised tribal leaders. Fearing that Amin would be defeated and replaced by a government of Muslim fundamentalists or—even worse—pro-American intellectuals, the Soviet Union launched an invasion on Christmas Eve aimed at removing Amin and replacing him with a more reliable strongman.

In late 1979, the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was torn apart by a civil war pitting the weak Communist government of Hafizullah Amin against several moderate and fundamentalist Muslim rebel armies. The war had been brought about by Amin’s incompetence and corruption, his vicious program of political repression, the massacre of entire village populations, and a ham-handed agrarian “reform” program that disenfranchised tribal leaders. Fearing that Amin would be defeated and replaced by a government of Muslim fundamentalists or—even worse—pro-American intellectuals, the Soviet Union launched an invasion on Christmas Eve aimed at removing Amin and replacing him with a more reliable strongman.To pave the way for the invasion, Soviet advisers with the Afghan Army tricked their clients into incapacitating themselves. In one case, the Soviets told an Afghan armored unit that new tanks were about to be delivered but that, due to shortages, the gas in the old tanks would have to be siphoned out. The Afghans obligingly siphoned gas out of their tanks, rendering them useless. In another instance, Soviet advisers told an Afghan unit to turn over all their ammunition for inspection, something that likewise was done without question.

A Former Prime Minister Declares Himself President

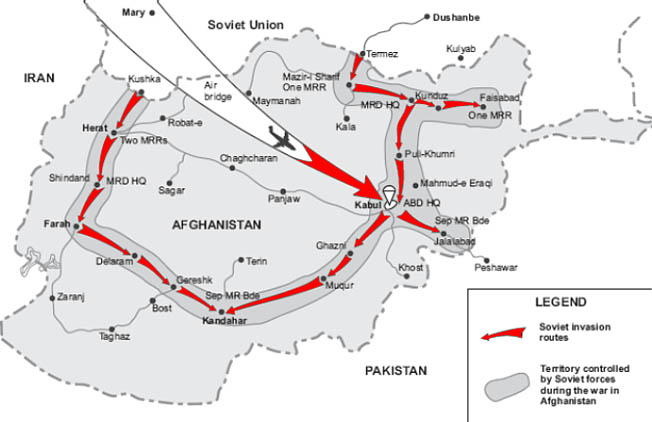

By the time the first Soviet transport planes landed at Kabul airport carrying elements of the 103rd Guards Airborne Division, the Afghan Army was largely incapable of fighting back. On December 27, the Soviet 5th Motorized Rifle Division rolled across the borders toward Herat, Shindahd, and Kandahar, while the 108th Motorized Rifle Division drove on Kabul. The 201st Motorized Rifle Division advanced toward Kunduz. That same day, Soviet troops captured the Kabul radio station and attacked the presidential palace, killing Amin. In a radio address broadcast from the Soviet Union, former prime minister Babrak Karmal, who had been handpicked by Soviet authorities, declared himself president.

The DRA army had an impressive strength on paper, numbering 13 infantry divisions and 22 independent brigades. There were also 40 separate regiments. This force was composed of at least 70 percent conscripts, including thousands of men who had been rounded up by government press-gangs and forced to serve in the army. What few volunteers there were usually became junior and noncommissioned officers. Despite the press gangs and financial incentives to volunteer, DRA army units were badly under strength, sometimes by as much as 40 percent. The army was decimated by desertions and riddled with mujahideen spies. Supplementing the army was the KHAD, or secret police, numbering 100,000 men.

Hope for Stabilizing the Region Was Failing

Soviet planners had hoped that the invasion and coup would stabilize the situation enough for the DRA army to take control. In fact, their strong-armed tactics devastated morale in the Afghan Army and led to further desertions and defections. Even worse, enraged mujahideen took to the field and engaged Soviet forces in open battle outside Kandahar, in Jalalabad, and along the Salang highway. After the Soviets’ massive firepower overwhelmed them, the mujahideen retreated into the mountains along the Afghan border and switched to guerrilla-style tactics. The Soviets followed.

The Red Army deliberately waged war on Afghan civilians and drove them over the border into Pakistan. By doing so, they hoped to deny the mujahideen local support and a native population to hide among. In 1980, the Soviets mounted a large-scale offensive into the Kunar Valley that resulted in the expulsion of nearly all of the valley’s 150,000 residents. A similar offensive was undertaken to the south in the Sultani Valley. Supporting these Soviet attacks were clearing operations south of Kabul and around Kandahar that destroyed dozens of villages. Similar operations were launched throughout the country in 1981, but with little long-term success.

Guerrilla Attacks and Civilian Casualties

In the face of the Soviet onslaught, mujahideen forces retreated into the mountains or melted into a population made friendly by repeated Soviet and Afghan Army atrocities. When the mujahideen did come out and fight, they subjected Soviet forces to a constant stream of guerrilla attacks. DRA troops were no match for the mujahideen. In daring assaults in April and September of 1981, the mujahideen temporarily seized Kandahar from DRA forces and left only after the Soviet Air Force bombed them. Compounding anti-Soviet sentiment brought about by the Red Army’s complete disregard for Afghan civilian casualties was the brutality of the common Soviet soldiers, who regularly took out their frustration on the Afghan populace. An Afghan farmer passing through a Soviet roadblock could count upon his valuables being stolen and his wife being raped. Mounted Soviet troops seemed to take great joy in shooting at Afghans along the road. Soviet advisers, officers, and NCOs treated their Afghan proxies with contempt.

The frustration of the Soviet fighting man was easy to understand. Soviet soldiers were conscripts who often received only three weeks of basic training before being sent to savage Afghanistan. Once there, a new recruit was bullied by veteran soldiers and brutal NCOs. Soldiers were badly paid, ill fed and clothed, and lived in tents. Many soldiers found relief from their situation in the form of the opium or locally produced alcohol. Hungry conscripts sometimes traded their weapons to the Afghans for food. Fevers and infections caused by unsanitary camp conditions decimated thousands of Soviet recruits.

Hills Swarming With Mujahideen

Despite the Soviets’ various campaigns of annihilation, the hills outside the major Afghan cities were swarming with mujahideen. Soviet army units were confined to their bases and traveled only on the main roads. Traveling at night in anything other than a large convoy was suicidal. The Soviets, like their American counterparts in Vietnam, were heavily reliant on helicopters for movement through the hostile countryside. Also mirroring the American approach in Southeast Asia, the Soviets used only a bare fraction of their military might, refusing to delegate more men and material than were absolutely necessary. They even went so far as to call the 40th Army in Afghanistan a “limited contingent of forces.”

By 1981, the mujahideen numbered as many as 150,000 fighters organized into seven main Sunni Islam parties. Three Islamic fundamentalist organizations had roots reaching back to the 1960s, and a fourth group formed in 1982 to serve as an umbrella organization and raise money for the cause throughout the Islamic world. There were also three “moderate” parties. These were formed after the 1978 coup, and although not as radical as the other four groups, they were still Muslim organizations. There were also three smaller Shiite groups with ties to Iran.

Excellent Fighters, but Poor Soldiers

The average mujahideen fighter was an illiterate farmer or herder. Although they were excellent fighters, mujahideen tended to be poor soldiers. They disliked field craft, were reluctant to crawl even when under fire, and were often unwilling to conduct sabotage missions, as these were not seen as glorious and honorable. They were terrified of Soviet land mines, which often maimed rather than killed—the former being considered a fate worse than death. Mujahideen saw firearms as a status symbol, and most were excellent shots. They took great pride in their centuries of tribal warfare and raiding, and consequently they believed that they had little to learn from Pakistani and Western advisers about how to fight a modern superpower.

In 1982, the closest thing the mujahideen had to a central command was the Afghan Bureau of the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence agency, or ISI. Led by General Mohammed Yousaf, the Afghan Bureau operated numerous training camps in the border area, provided advisers from the Pakistani Army, and funneled supplies to the mujahideen. These were provided by the American Central Intelligence Agency, which bought weapons from sellers all over the world, including China, Egypt, and, ironically, Israel, which sold equipment it had captured during the various Arab-Israeli wars. The Afghan Bureau also tried to coordinate mujahideen attacks. This inevitably led to conflicts. Afghan leaders were interested in disrupting Soviet supply lines and sabotaging infrastructure, while mujahideen commanders wanted to engage Soviet troops in open combat. Still, some highly valuable and successful attacks were carried out. In one bold raid, mujahideen fighters loyal to Ahmad Shah Massoud fought their way onto Bagram Air Base, attacked Soviet barracks packed with sleeping troops, and hit the airstrip, destroying 23 aircraft. They then retreated to their bases in the nearby Panjshir Valley.

Ahmad Shah Massoud

In the aftermath of the airport raid, the Soviets launched a massive counteroffensive against the Panjshir Valley designed to destroy mujahideen forces and install permanent DRA army garrisons there. The Panjshir Valley juts out from the Hindu Kush, pointing like a dagger at Kabul and Bagram Air Base. The Salang highway, the road over which 90 percent of the Soviets’ supplies were carried, went right past the valley entrance. Running through the valley is the Panjshir River. The banks were dotted with villages, farms, and vineyards. Dozens of canyons were home to small, isolated villages. At the beginning of the war, some 100,000 people of Tadjik origin resided there.

The valley was also home to the mujahideen’s most feared commander, Ahmad Shah Massoud. Born in 1953 in Herat, Massoud was part of Afghanistan’s minuscule educated class, having attended the French-run Lycee Istaqlal and the Russian Polytechnique Institute (both located in Kabul) where he studied engineering. Massoud was an accomplished athlete, voracious reader, and spoke French, Pashto, and Dari. During his time in Kabul, he became politically active, joining the Jamiat-e Islami party. When Mohammad Daoud seized power in 1974, Massoud fled to Pakistan, where he underwent military training and studied the art of war, particularly the campaigns of Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, and North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap. He returned to Afghanistan in 1978 and began operations in the Panjshir Valley, quickly gaining a cadre of tough, loyal followers who waged a guerrilla war against DRA forces.By 1980, Massoud controlled the entire valley.

No comments:

Post a Comment