Anit Mukherjee

India’s COVID-19 Lockdown and its aftermath

On March 24, with little advance notice, India’s federal government announced a strict countrywide lockdown to contain the spread of COVID-19. Within two days, it also announced a relief package providing cash transfers to women, elderly and farmers, as well as food grains through the Public Distribution System (PDS). In spite of these measures, millions of migrants – mostly urban informal sector workers - made a desperate attempt to return to their villages, often walking several hundred kilometers over many days to get there. The chaotic scenes witnessed during the first week of India’s lockdown underscored the precariousness of their livelihoods and highlighted the shortcomings in India’s extensive social safety net that caters to nearly 80 percent of its 1.3 billion people.

For nearly a decade, India has invested in building a digital infrastructure to transfer social benefits to its citizens directly to their bank accounts. Known as the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) platform, it currently includes 380 schemes run by 52 ministries of the federal government. State governments can use the DBT platform for their own cash transfer schemes as well. India also has a clear strategy in place to enable digital delivery of public services, subsidies and transfers. Known as the “JAM trinity”, the objective is to utilize universal coverage of its biometric ID system, Aadhaar, to expand bank account ownership through the Jan Dhan financial inclusion program and leverage mobile technology to reach final beneficiaries of social assistance. The COVID-19 lockdown provided a test of whether these investments in digital infrastructure would pay off and help the government deliver relief quickly and efficiently.

Early assessments suggest that this was indeed the case. The government transferred cash to over 200 million women-owned Jan Dhan bank accounts within a week of the announcement. However, the reasons for the migrant crisis soon became clear. It has been pointed out that while the government knows ‘how to pay’, it does not have an integrated view of ‘who to pay to’. Unlike countries such as Brazil or Pakistan, India does not have a unified beneficiary database or social registry that could be used to identify, target, register and pay those in need of assistance. Administration of benefits is fragmented – they are a mix of in-kind, voucher and cash transfer schemes run by different ministries, departments and agencies. More importantly, India’s states have their own social assistance programs while at the same time coordinate, supplement and implement federal schemes. This patchwork of financing and delivery of social assistance means that even though some states have implemented in-state portability for certain programs such as the Public Distribution System for foodgrains (PDS) and social pensions, in general benefits are not transferable across state jurisdictions.

Reaching migrants through cash transfers: Bihar’s Corona Sahayata (assistance) program

With the lockdown eliminating their sources of income, the lack of access to social assistance was an important consideration for migrants to undertake the journey to get back ‘home’, the place where they are registered to receive them. While some made it back to their hometowns and villages, the majority of migrants were left stranded in the cities where they worked. As India’s economy ground to a halt, the situation of those employed in the informal sector, in particular, became increasingly desperate. Many came from Bihar, a north Indian state of 120 million people. Responding to their plea for help, on April 7, the State government launched the ‘Corona Sahayata (Assistance)’ scheme to provide cash assistance through payments into bank accounts to tide over the immediate crisis.

In the global context, Bihar’s emergency assistance program is not unique.[1] Many countries have implemented social transfers to support informal workers or the “new poor” using digital transfers. However, Bihar’s initiative is a rare example of a sub-national government’s effort to identify, onboard and pay a specific segment of the population (i.e., migrants) adversely affected by the pandemic, doing so remotely, at scale and without the benefit of an existing database, using a “digital first” identification and payments approach to transfer funds quickly and efficiently.

Seen in that context, we believe that Bihar’s case holds lessons both for India and globally. As we have documented in a recent CGD policy paper, COVID-19 creates additional challenges that policymakers need to consider while designing and implementing new social assistance programs. This note describes how Bihar addressed the policy challenges to implement the program and the lessons it holds for India and globally.

Box 1: Rambabu’s story

After finishing high school two years ago, Rambabu Kumar left his native village in Bihar for Gujarat, an industrial state in western India 2000 km away. He got a job as a trainee in a manufacturing plant and became a machine operator after a year with a regular salary. But life was interrupted for the 22 year-old when the Indian government announced the national lockdown on March 24. The company refused to pay its employees, urging them to “go home”. With bus and train services suspended, Rambabu had no option but to wait for the lockdown to be lifted – his home was too far to walk.

Rambabu was forced to dip into his meagre savings to buy provisions from the local store. His ration card was registered in Bihar which made him ineligible to get food grains from PDS shops in Gujarat. His brother who lived in the village informed Rambabu about Corona Assistance program after it was announced on April 7. He decided to apply for it, as did nearly 3 million others who were in a similar situation.

Before leaving for Gujarat, Rambabu had opened a bank account in Bihar through the Jan Dhan financial inclusion program, fulfilling one of the main criteria to receive the transfer. Rambabu had a smartphone so he downloaded the app and watched YouTube videos to learn how to apply for the assistance. His bank account was linked to his Aadhaar and mobile number, so the application process was relatively seamless. He got an SMS to confirm that his application was received and another one four days later to inform him about the bank deposit. This came as a huge relief – he went to the local grocery store-cum-bank agent, withdrew Rs.1000 paying a 1% cash out fee, paid his dues with the store and used the rest to buy a train ticket back to Bihar. But not everyone was so fortunate – his two friends also applied for the Corona Assistance but their applications were rejected. They did not know the reason why.

At the time of this interview, Rambabu was living with his family in his native village. He regularly gets phone calls from his former employers requesting him to return to his job in Gujarat. He said he is seriously considering doing so to support his family through the COVID-19 crisis.

Design and delivery

The objective of Bihar’s Corona Assistance program was relatively straightforward. It was to transfer Rs.1000 ($15) to the bank accounts of Bihari migrant workers who were stranded outside the state due to the lockdown and who were interested to return safely to Bihar. The database of registered beneficiaries was also used a few weeks later when special migrant trains (Shramik Specials) were operated from large urban centers all over India to Bihar. Hence, this registration process also helped in logistics at a time when regular railway ticketing processes were suspended owing to the lockdown.

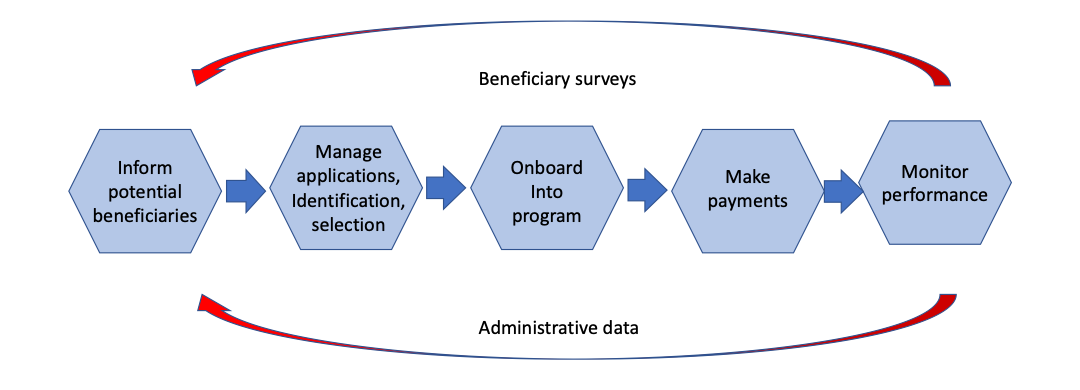

However, the design and implementation were complex. Given the circumstances of the pandemic, the scheme had to be ‘end-to-end’ digital across the whole social transfer value chain, with clear communication strategy, remote registration, verification, enrollment and payment.

The most critical factor was the identification of beneficiaries and verification of their eligibility– “who to pay”. Once that was successful, the “how to pay” was relatively simple. The DBT platform ensured that it was done quickly and efficiently, provided the financial information supplied was correct. As we shall see below, this was not the case in many instances, leading to confusion at best and denial of assistance at worst.

a. Information and onboarding

Cash transfer programs need clear communication of conditions of eligibility and documentation. Without that, administrative systems can be overwhelmed with spurious applications that slow down disbursement and erode trust in the capacity of the state to deliver on its promises. Digital technology – ID, mobile communication and digital payments - can be used to underpin the delivery infrastructure and help reach the target group efficiently and minimize exclusion errors.

For Bihar’s Corona Assistance, it was made clear that the scheme was only for those who were domiciled in the state but temporarily living in other parts of the country. It required applicants to provide proof of residence outside Bihar and bank account registered in Bihar to receive the assistance. Qualitative research shows that both of these were difficult to fulfill for many migrants, especially those working in the urban informal sector.[2]

The onboarding process was wholly digital. Those with smartphones could download an Android application (Corona Sahayata App) to complete the registration. People without smartphones could register through the website of the Bihar State Disaster Management Agency, the nodal agency in charge of program implementation. However, even those applying through the website were required to possess a mobile phone (or have access to one) to receive a one-time password, without which they would not be able to complete the application process.

With these eligibility rules, the Bihar government received 2.9 million applications within a month of the launch of the scheme, out of which 2.03 million were verified and paid by May 24. Even with the limited financial support and other constraints, the rollout and payment were rapid, addressing the primary objective of delivering compensation in a time of crisis to those who needed it most. [3]

b. Identification and eligibility screening

Verified identity: The scheme mandated Aadhaar as the only accepted identification document. Applicants had to upload a snapshot or a scanned copy of their Aadhaar credential. This step was needed to triangulate identification information – recent photo, Aadhaar details and mobile number. In addition, they had to upload a photograph (selfie was accepted for those using the app) which was matched against the one in their Aadhaar credential. While we are not aware of the exact backend process of verifying photographs, this is a novel way to undertake remote biometric verification using a face-enabled ID database – something that has not been used previously in the context of social assistance programs.

Physical address: Since the objective of the scheme was to provide relief to migrants from the state stranded outside due to COVID-19 lockdown, it was necessary to furnish proof of a physical address at the current place of residence. To establish that the person is from Bihar, the program stipulated that s/he had to provide details of a bank account registered in the state. It is unclear why the government decided not to use the information available from Aadhaar, voter’s ID, driving license or ration card which are accepted in most government programs. This was an interesting design feature, but we do not have sufficient information to determine if this proved to be exclusionary or not.

Financial address: As noted above, applicants could receive the benefits only if they had a bank account registered in Bihar. The last step was to provide information of the beneficiary bank account in Bihar (including the IFSC or Routing Code). This increased the risk of human error while typing multiple numbers, which caused many of the applications to be rejected, requiring beneficiaries to go through the process of re-applying for the benefit. This meant additional hardship for people who did not have smartphones, having to find alternative means to access the government’s online portal in the middle of the stringent lockdown. Moreover, the bank account had to be linked to Aadhaar to receive the payment, adding another layer of uniqueness but also potential for exclusion of those in need.

c. Payment mechanism and grievance redressal

As per the information released by the Government of Bihar (May 24), just over two-thirds of the applicants were successfully paid through the DBT platform within the first two months of implementation. Detailed implementation data is not publicly available making it difficult to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the scheme.

On the payments side, it has been reported that the cash assistance was insufficient given the need faced by migrants. The application process was cumbersome and many did not receive their payments due to incorrect banking information. A common problem was that many accounts were inactive which required updating KYC to receive the compensation. While this difficult even in normal circumstances, the lockdowns made it almost impossible for migrants to go through the process of activating their accounts to obtain what is a relatively small, one-off grant. The costs, it seems, outweighed the benefits.

Compared to other emergency relief programs announced by the federal government, Bihar’s Corona Assistance scheme was limited in scope and scale. However, it filled an important need and a significant gap in federal response which did not explicitly target stranded migrants – the previously invisible ‘new poor’ whose existence was brought to stark relief by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lessons from Bihar’s Corona Assistance program

Bihar’s initiative addressed a critical need for cash assistance that had to be designed, directed and delivered digitally. We do not, however, have enough data to make a judgement on its efficiency and impact. Specifically, we would like to obtain weekly registration and payment information to understand how well the scheme design translated into actual disbursement. Also, we are not aware of any beneficiary level surveys that can help us assess the experience and impact of the scheme along the social transfer value chain. Finally, it would be helpful to understand measures put in place to reduce exclusion (there are reports of difficulty in accessing the helpline) and obtain feedback, and whether such processes were used to re-design the program and make it more effective and efficient.

Even with these caveats, Bihar’s case indicates several lessons for over 200 countries delivering COVID-19 social assistance payments to over a billion new beneficiaries. Even with a unique, universal and digital ID platform, high rates of bank account and mobile phone ownership, identifying and paying migrants is a challenging proposition. Digital technologies help to quickly rollout and scale up programs but a lack of unified social registry is a serious constraint. Complex design, eligibility norms and ID verification can be critical roadblocks. Finally, receiving and accessing the cash transfer is not straightforward and bank accounts may not always be the best option to receive emergency payments especially with restrictions to mobility and access to cash out points.

Exclusion remains a daunting challenge. Digital first programs often ignore people at the bottom of the digital pyramid with the least digital capacity – Bihar’s program is no exception. People with smartphones could use the Android application (iOS was not supported) to register for the program while those without it had to overcome additional hurdles to complete the process. Last mile payment through bank accounts and many people faced problems entering correct bank account details, dormant accounts requiring KYC, and to cash out once the assistance was received. Bihar’s program could have paid to digital wallets or provided e-vouchers to cash out at bank or mobile money agent points, as was done in Togo, Namibia and Colombia - it was a policy choice not to do so.

In spite of all the drawbacks, Bihar’s Corona Assistance managed to reach over two million people within few weeks of its launch. This provides us with a case study on how to design a new program to target the “new poor”, using digital mechanisms and platforms to identify, onboard and transfer social assistance remotely, overcoming the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

No comments:

Post a Comment