By Shawn McCann and Damien O’Connell

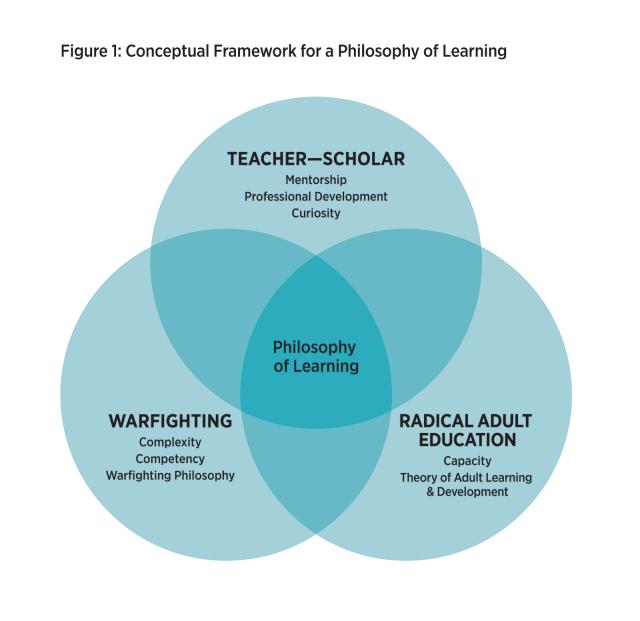

A major proponent of professional military education, Lieutenant General James C. Breckinridge called on the Marine Corps to adopt a culture of curiosity and challenging the status quo. As a follow-up to our previous article, “A Response to the Marine Corps’ New Doctrine on Learning,” we offer an alternative conceptual framework for Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 7 Learning (MCDP 7). We follow the process laid out by General Breckinridge—of curiosity, research, discourse, recommendation, criticism, and improvement—to encourage the Marine Corps to adopt a more comprehensive philosophy of learning. We offer a three-lens conceptual framework consisting of warfighting, the teacher-scholar relationship, and critical or radical adult education and training. Radical adult training and education refers to our capacity for action (training) and a learner-centered manner of facilitating the development of autonomous critical thinkers (education).

As we mentioned in the first article, MCDP 7 does a commendable job of stressing the importance of learning, but it lacks a firm conceptual framework. Marines have already begun referencing MCDP 7 for their scholarly and practical work. Therefore, MCDP 7 should present a sturdy and sound philosophy from which Marines can build a practice of personal and professional development. Unfortunately, MCDP 7 makes little use of the field of adult learning and development and focuses instead on instructional design concepts, such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs). Our conceptual framework (as depicted in Figure 1) leverages radical adult education and provides Marines with a more cohesive and complete mental model for learning. The lens of radical adult education will provide Marines with the necessary scholarship and relevant concepts to make learning an integral part of their practice as warfighters.

The First Lens: Warfighting

Warfighting, as it does in the current version of MCDP 7, provides Marines with the context, or the who, what, where, when, and why of learning. Through this lens, Marines learn about the inherent complexity of warfare and the competencies required to succeed in the chaos of combat. Warfighting provides Marines with a foundational understanding of the challenges and demands of the profession of arms.

Although MCDP 7 does introduce this context and the relationship between warfighting and learning, it fails to deliver anything particularly useful to Marines. For instance, on pages 3–4, MCDP 7 views warfighting through the lens of instructional design instead of adult learning and development. The authors of MCDP 7 use KSAs in their definition of learning, and we assert that KSAs describe the objectives of specific training more accurately than they do the process of learning. Instead, MCDP 7 should leave granularities of designing, developing, and delivering training and/or education to follow-on supplementary publications and focus on a learning paradigm matching the intellectual and theoretical depth of Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1 Warfighting.

The Second Lens: Teacher-Scholar Relationships

The Marines Corps has long encouraged its leaders to develop a teacher-scholar relationship with their Marines. Lieutenant General John A. Lejeune’s urging for the teacher-scholar concept provides a historical precedence and cultural foundation for today’s leaders to create mentor relationships that support Marines in their learning and development. In a recent interview, Major General Ray Smith, one of the Corps’ most decorated combat leaders since World War II, advocated for the enduring teacher-scholar relationship and endeavored to live his career following Lejeune’s guidance. General James Mattis did the same. MCDP 7, however, only mentions the concept once in the final chapter. The teacher-scholar relationship is a cornerstone of our framework. In our conception, however, we broaden the relationship beyond that of the original officer-enlisted construct to include all Marines. We also assert that the teacher-scholar concept refers to both groups learning together. Lastly, this lens includes the spectrum of military professional development (from joint professional military education to the small unit leader), the mentorship relationship itself, and the necessary intellectual environment for any of the above to take place.

The Third Lens: Radical Adult Education

Missing from MCDP 7 and required for Marines to thrive as teacher-scholars and warfighters is the third lens of radical adult education. Radical adult education, when combined with the other two lenses, provides Marines with the philosophical footing for developing a capacity to learn through the complexity of war. The capacity to learn through complexity in real time allows Marines to gain an intellectual advantage over their foes.

Radical: Far Reaching and Thorough Change

In the context of military education, the word “radical” has no political meaning. It indicates the measure of change required of the Marine Corps’ approach to learning. Radical adult education urges Marines to challenge the status quo, just as Lieutenant General Breckinridge advocated. It means Marines must purposefully examine and tactfully challenge the validity of their commands’ standing operating procedures and even service-level concepts, such as expeditionary advanced base operations. The Corps’ warfighting philosophy requires leaders at the lowest levels to think, decide, and act. To do this in the 21st century, Marines will need to challenge not only their own assumptions, but also the assumptions of their peers, commanders, and the Marine Corps itself. In doing so, Marines will not devalue the experiences of veterans. Nor will they disqualify the adage that “everything old is new again.” In fact, surfacing and testing assumptions will allow Marines to get the most out of those experiences. This is where experiential learning, another component of the Radical Adult Education lens, comes into play.

Experiential Learning

As General Alfred M. Gray, 29th Commandant of the Marine Corps, stated, “There is no substitute for the tested veterans telling how they survived and how things work.” Radicalizing learning in the Marine Corps will allow Marines to get the most out of those stories of survival. Experiential learning provides a framework for how learning occurs and applies to both training and education.

However, the most appropriate learning does not emerge naturally from experience. Rather, it requires Marines to deliberately reflect on their experiences to avoid reinforcing outdated ideas. And applying a purposeful reflective practice allows Marines to get the most beneficial learning out of their experiences. When Marines push beyond this type of reflection and instead critically reflect, or challenge their assumptions, beliefs, and values, they can open themselves up a more significant type of learning—transformative learning.

Transformative Learning

Transformative learning goes far beyond an indoctrination process, such as recruit training, where new experiences shape civilians into Marines. Transformative learning is more than just good, eye-opening learning. Transformative learning changes how we know. It is “a process by which previously uncritically assimilated assumptions, beliefs, values, and perspectives are questioned and thereby become more open, permeable, and better validated.”

Traditional learning paradigms (not to be confused with “wrong” or “useless” paradigms) focus on providing content: facts, figures, processes, performance steps, etc. We have witnessed numerous teacher-centered Socratic seminars in both enlisted and officer professional military education, with facilitators steering the conversation to cover their main ideas, outcome, or objective. This approach treats learners as an empty cup and the facilitator simply needing to fill that cup. By contrast, transformative learning does not seek to fill the cup but to change its capacity. Because transformative learning describes the development of that type of capacity, it is worthy of inclusion in a doctrine on learning.

A final ingredient to our framework is creating and sustaining a culture of curiosity, a condition necessary for any long-term meaningful change in how we train and educate Marines.

A Culture of Curiosity

Without accepting curiosity as a required trait for Marines, no doctrine, directive, or order will perpetuate a culture of learning. Curiosity is a motivator for learning and aptly listed as the first step in General Breckinridge’s process for improvement. A vital component for collecting data for decision making, curiosity also enhances learning and contributes to adult development. To sustain curiosity, Marines must learn how to formulate and ask questions, and leaders must learn how to employ active and empathic listening. Leaders who practice listening can provide an environment that cultivates curiosity in learners. Otherwise, learners may engage in what John Dewey called collateral learning, where students disengage from the material being taught and even learn to develop an emotional revulsion to it.

MCDP 7 mentions the words “curiosity” or “curious” six times, but mostly in reference to the individual Marine’s responsibility. It therefore misses the opportunity to address the role of the Marine Corps and its leaders in encouraging Marines to practice curiosity. In other words, without curiosity there is no lifelong learning.

MCDP 7 includes terms like curiosity as it makes the case for learning as a doctrine. It mentions warfighting throughout its text and references a teacher-scholar relationship when discussing the importance of learning and humility. However, MCDP 7 lacks accuracy when introducing key terms, concepts, theory, and in providing examples. On pages 4–7, MCDP 7 seems to recommend maintaining the status quo of learning in the Marine Corps. It fails to differentiate between a philosophy of learning and instructional design techniques, even including the KSA construct in its definition of learning. The Marine Corps already asks Marines to memorize information, conduct many repetitions of exercises, and achieve brilliance in the basics. Revising MCDP 7 through the combined lenses of warfighter, teacher-scholar, and radical adult educator can provide the Marine Corps with a more cohesive and complete learning philosophy.

To implement this three-lens framework, the Marine Corps must shift from its current understanding of learning and require all leaders to stop expecting big results from small changes made to training and education. Leaders must use the appropriate tool to, as MCDP 7 calls for, “create a culture of continuous learning and professional competence.” Radical adult education, framed in the context of warfighting and supported by teacher-scholar relationships, provides the right hammer for this nail.

No comments:

Post a Comment