by Patrick Mendis Joey Wang

In its continuing tensions with Japan, China sailed its ships near the Senkaku (Diaoyu in Chinese) Islands for 111-days straight beginning on April 14 until August 3, ending Beijing’s pressure on Tokyo only due to the approaching Typhoon Hagupit. These uninhabited islets in the East China Sea are claimed by China and Taiwan even as Beijing continues to challenge Washington in the South China Sea, Taipei in the Taiwan Strait, and New Delhi on border issues. If history is any guide, then China’s overall actions appear to be following the pattern of post-Meiji restoration (1868–1912) Japan.

Like China, Japan in the nineteenth century was too weak politically and too backward economically to repel the advances of the West. However, Japan’s view of its role in the world would depart from that of China. Whereas China’s place in the world remained largely unchanged well into the middle of the twentieth century, Japan would embark on modernization before 1900, build on a successful “industrial economy” and preserving the “empire,” according to William Beasley in his definitive book, Japanese Imperialism, 1894–1945.

Dale Copeland also explains in Economic Interdependence and War that the ruling elite of Japan advocated the “twin pillars” of “rich country, strong army” and “production promotion” to catch up to the great powers of Britain, France, and Germany—and develop the national goals of industrialization and economic growth.

The Japanese Monroe Doctrine

At the turn of the twentieth century, the idea of a Japanese Monroe Doctrine began to appear. There was some elasticity to this meaning, to be sure. But, according to the now-unclassified CIA report, the indisputable consensus among the Japanese was that Europeans and Americans had reduced the Asiatic countries to semi-colonial status. In the most assertive interpretation, it meant that all Western political influence should be expunged from East Asia and the “entire region should be organized under Japanese political control.”

In fact, the slogan for the Japanese Monroe Doctrine was “Asia for Asiatics.” In his “Japanese Monroe Doctrine” in Foreign Affairs, George Blakeslee wrote that implicit within this policy was the “right of Japanese leadership in the Far East.”

The Eight Corners of the World Beneath One Roof

The Japanese expansionist agenda continued with the fall of France and the Netherlands in 1940, giving Tokyo an opportunity to expand into the European holdings in Asia. Shortly thereafter, according to the CIA report, Japan would establish the Greater East Asia (GEA) “Co-Prosperity Sphere” in a broader application of the Japanese Monroe Doctrine. Incorporating the ideas of economic cooperation, Tokyo also established the GEA Ministry in its governance structure.

Tokyo later defined the policy as “an international order based upon common prosperity.” It was also front-loaded with the “traditional Japanese symbolism of Hakko ichiu, ‘the eight corners of the world beneath one roof’” as well as the “pragmatic policy of armed expansion.”

Gerald Haines explains in “American Myopia and the Japanese Monroe Doctrine, 1931–1941” that the primary motivations for the GEA was “securing East Asia for the economic well-being of Japan.” In “Closing Doors Against Japan” in the Far Eastern Survey, Ethel Dietrich also identified that Japanese exports were becoming increasingly squeezed by the West’s trade barriers. To ensure that Tokyo had a secure supply of raw materials as well as a market for its finished products, Japan hoped to create an economically and commercially linked bloc of states that would be resilient to external economic pressures, just as Great Britain and the United States had for themselves. The Japanese Monroe Doctrine provided the perfect rationale for Tokyo’s GEA policy.

China’s Post-Meiji Restoration Redux

Asian history is now repeating itself. Like Japan, China is now another textbook example of power from wealth—and wealth from trade and commerce. For well over a century, China suffered under the West’s humiliation. Indeed, it suffered concurrent humiliations under Japanese aggression while fighting its own civil war.

It was not until 1978 when Deng Xiaoping opened China up to the world and began adopting market-oriented reforms and allowing private enterprises to flourish. According to Nicholas Lardy in the Financial Times, these companies became the engine that powered the Chinese economy as it made significant contributions “to China’s stellar output, employment, and export growth.”

As a result of this wealth, however, China is also exhibiting some classic patterns of historical rage. Like Japan, Beijing is now implementing its own version of the “Monroe Doctrine” in the East and South China Seas. Since 2013, for example, it has reclaimed thirty-two hundred acres of new land in the Spratly and Paracel Islands and established twenty-seven outposts, militarizing a number of them despite the Hague’s ruling rejecting Beijing’s claims to the South China Sea (SCS).

This is central to China’s primacy objectives because it would not only give China tactical and operational control of the SCS, it could significantly control the economies of the East and South China Sea countries by interdicting maritime shipping from Singapore to Japan.

The control of the East and South China Seas would also facilitate China’s ultimate objective of unification with Taiwan by force and using it as a platform for pushing US and Western influence out of Asia. As part of this grand strategy, China has embarked on building amphibious forces to challenge “U.S. supremacy beyond Asia” with the primary objective to not only project power far from home, but “also strengthening its ability to invade Taiwan.”

China is also aggressively probing Japanese air defenses as part of what China considers to be some unfinished business with Japan. If there are any doubts about China’s lingering and justifiable historical grievances, it is likely no accident that China’s first indigenously built aircraft carrier has been commissioned the “Shandong”— a colonial province that was ceded to Japan from Germany after World War I.

A Shared Regional Security

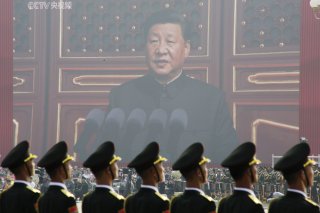

Under President Xi Jinping, China has likely done with Deng’s “hiding and biding” and now sees China as Asia’s rightful heir, much as Japan had done at the turn of the twentieth century.

Surely, China’s historical indignation is justified. Yet, Beijing’s primal desire to exact revenge on its neighbors is not only destabilizing global security but has no benefit that would justify its undertakings beyond nationalist self-satisfaction.

History teaches that which cannot be changed. China’s actions, in making the future, are telling the world what Beijing intends to do with that history. Indeed, these are the reasons why the United States and the West are (and must continue to be) committed to maintaining peace and stability in the region.

Patrick Mendis, a former American diplomat and a military professor, is a Taiwan fellow of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of China and a distinguished visiting professor of global affairs at the National Chengchi University as well as a senior fellow of the Taiwan Center for Security Studies in Taipei. Joey Wang is a defense analyst in the United States. They are alumni of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. The views expressed in this analysis neither represent the official positions of the current or past institutional affiliations nor the respective governments.

No comments:

Post a Comment