By: Nicholas J. Myers

Executive Summary

Russia’s last friend on its border with Europe, Belarus acquired new significance for Russian strategy after the emergence of an anti-Russian regime in Kyiv in 2014. However, Moscow takes little interest in Minsk’s policies even as Russia’s Western High Command relies upon Belarusian cooperation in its contingency planning for conflict in continental Europe. Analysis of Russian military exercises and diplomatic patterns since 2017 shows how the Western High Command is thinking about future war with NATO in each of its three strategic directions.

In the northwestern direction—encompassing the Baltic States and coastal Poland—a compliant Belarus plays into the Russian high command’s planning as a staging area from which to take control of east-west rail links to isolated Kaliningrad Oblast. In the western strategic direction, mainly targeting Poland, Russian radars on Belarusian soil and Belarusian air-defense assets as well as Belarusian forces may be expected to defend supply lines through Belarus during a broader Russia-NATO confrontation. Losing Belarus would significantly impact Russian power projection, removing Warsaw from the reach of Russian ground forces without committing virtually its entire armed forces to the task. Belarus appears to play the most indirect role in the southwestern direction, covering Ukraine: mainly serving for Moscow’s war planners as a Russian salient, complicating European military support for Ukraine in wartime conditions given the presence of CSTO air-defense assets in Belarus. At the same time, if Russian land forces are able to use Belarus as a staging ground for escalated conflict with Ukraine or simply threaten to do so, this would force Kyiv to withdraw its military front line significantly further westward, leaving the capital region significantly more vulnerable.

A Belarusian exit from Moscow’s security planning—whether through neutrality or a changed geopolitical orientation—would seriously complicate Russian military thinking in Europe, significantly elevate Poland’s security and strategic influence, and potentially banish Moscow’s military threat from the North European plain for the first time in 500 years. However, such a transformation would put Belarus in an extremely precarious political situation that would be difficult to sustain. These considerations underline the significance of the current instability in Belarus following President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s contested reelection on August 9, 2020. For as long as the current present Belarusian government remains politically vulnerable, it raises the risks of Minsk losing its sovereign freedom of maneuver and adherence to de facto neutrality in the face of Russian pressure to join Moscow in the latter’s strategic standoff with the West.

Introduction

Tasked with defending Russia from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Western High Command of the Russian Federation holds a prominent place in the country’s security architecture. The command was created as part of former Defense Minister Anatoly Serdyukov’s broader reform of the Russian Armed Forces’ command-and-control structure. Most of its forces are supplied by the Western Military District, which was created at the same time by combining the preceding Moscow and Leningrad military districts.

Since 2014, ongoing overt strategic rivalry between Russia and the West has increased visibility for this command. Until that time, the Western High Command had focused on using next-generation technologies to reduce demand for massing force. Since the outbreak of war in Donbas, however, Russia has greatly increased its force in the West, standing up a tank army around Moscow and two divisions on the Ukrainian border. Though technological modernization remained a priority, it no longer offset an absence of force but complemented it.

This paper assesses how Russian diplomatic and military bureaucratic behavior reflects the Western High Command’s current contingency planning for war in Europe. And in assessing the state of Russian military modernization on its European border, it the following study will specifically evaluate the importance of Belarus to current Russian strategic thinking.

How Russia Perceives Its Western Neighbors

Since the end of the Cold War, Russia has had a fraught relationship with Europe. Western investment entered the undercapitalized Russian economy in the early years of President Vladimir Putin’s regime. In return, Russian natural gas not only heated Europe but also repaid the Soviet Union’s legacy debt.[1] However, the enlargement of the NATO strategic alliance into former Warsaw Pact territory and the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania helped sustain a residual Russian security skepticism of the West. In 2019, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall claimed that the hope for a “peaceful, prosperous Europe without dividing lines” was “not realized.”[2]

When these tensions exploded into military conflict in the 2014 Ukraine crisis, Europe established a serious sanctions regime targeting Russia[3] and revitalized NATO’s historic mission of defending Europe.[4] But at the same time, long-obscured fault lines in Europe crystallized in Russian government messaging: Moscow demonized any European NATO member state supporting the initiatives of collective defense and deterrence, calling them “Russophobic” policies that prioritized war over their citizens’ prosperity while justifying raised defense spending to appease the United States.[5] Anti-Western political figures, already in vogue after the 2011–2012 anti-Putin demonstrations in Russia, became the exclusive voice of Russian opinion in the state-controlled media.[6]

Russian diplomatic officials had hoped that the election of Donald Trump as President of the United States would reduce Washington’s interest in backing a pro-Western regime in Ukraine.[7] However, bipartisan support for assisting Ukraine continued. Meanwhile, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania successfully lobbied for a ramped-up and enduring NATO conventional force presence in their region to deter potential Russian aggression.[8]

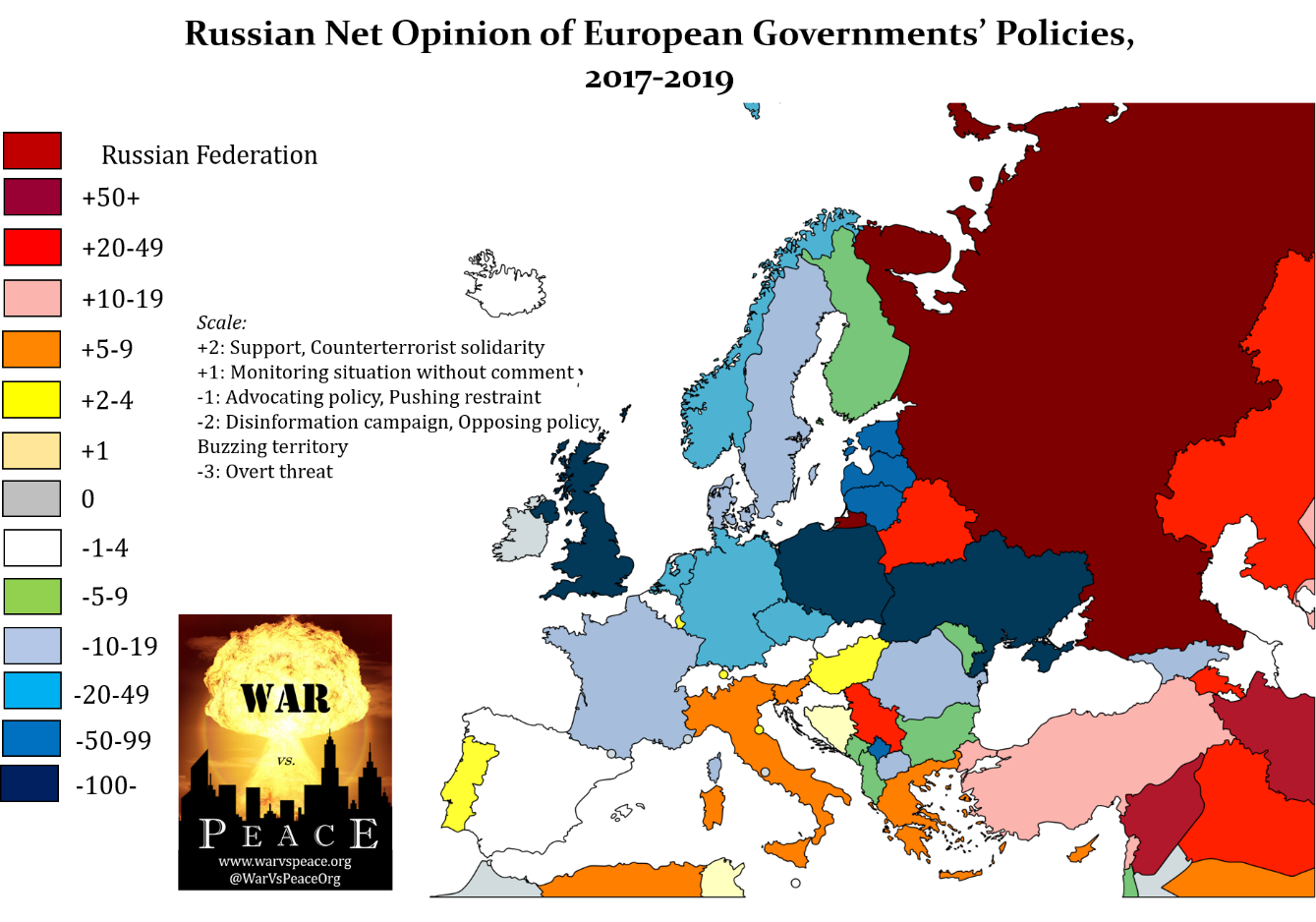

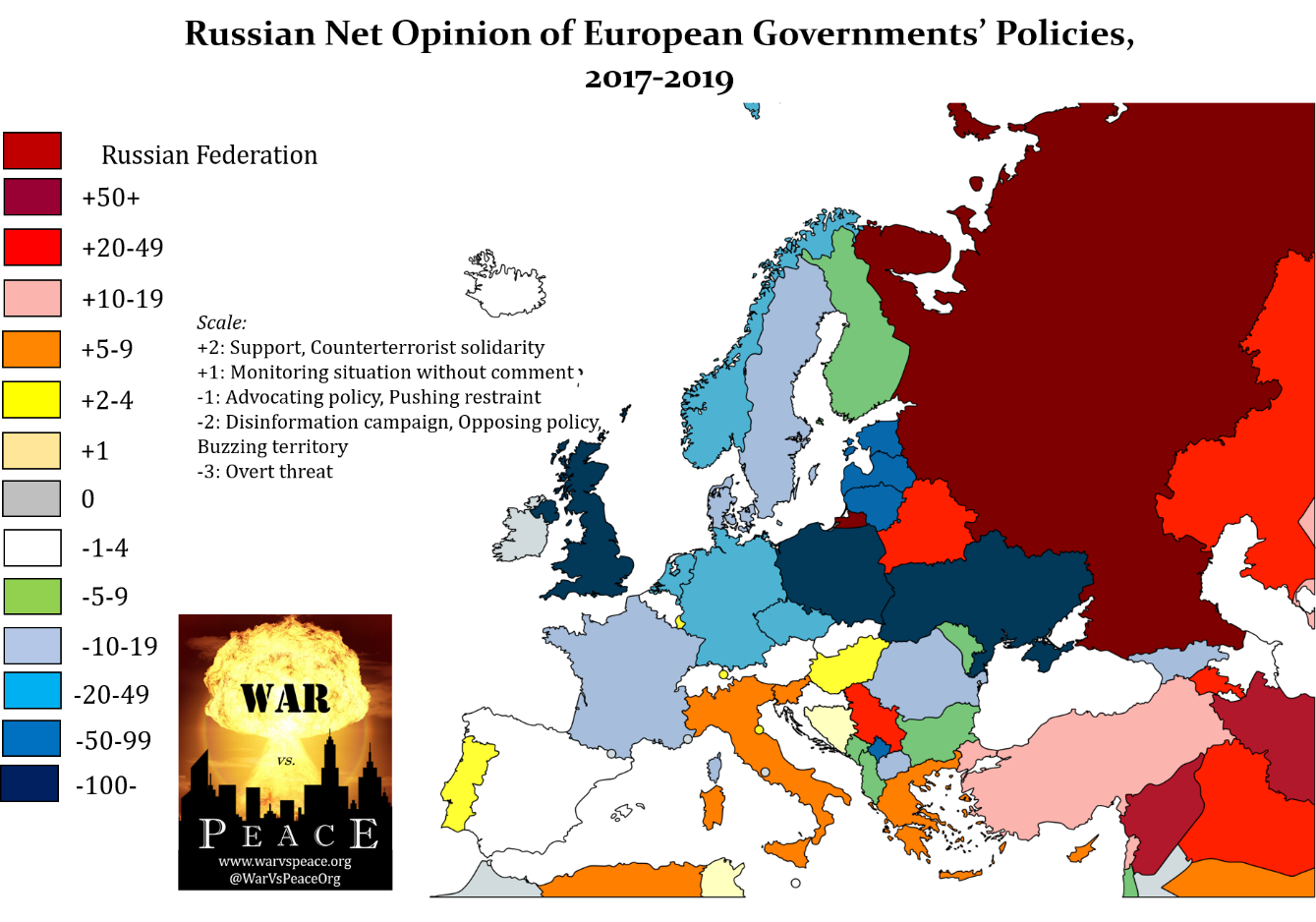

This divide has created a stark fissure in Europe. Map 1 depicts Russian perceptions of Europe by the frequency of diplomatic statements in favor of or against individual European states’ policies since the start of the Trump administration, with higher numbers/more red color denoting what Moscow perceives as friendlier states. As the conflict in Ukraine is already militarized, Russia has been forced to keep its military contingency plans for Europe updated to answer recent developments in NATO, even if the probability of a conventional war between Russia and the West remains quite low.

Map 1. Russian Net Opinion of European Governments’ Policies, 2017–2019

Compiled from official Russian government website press releases.

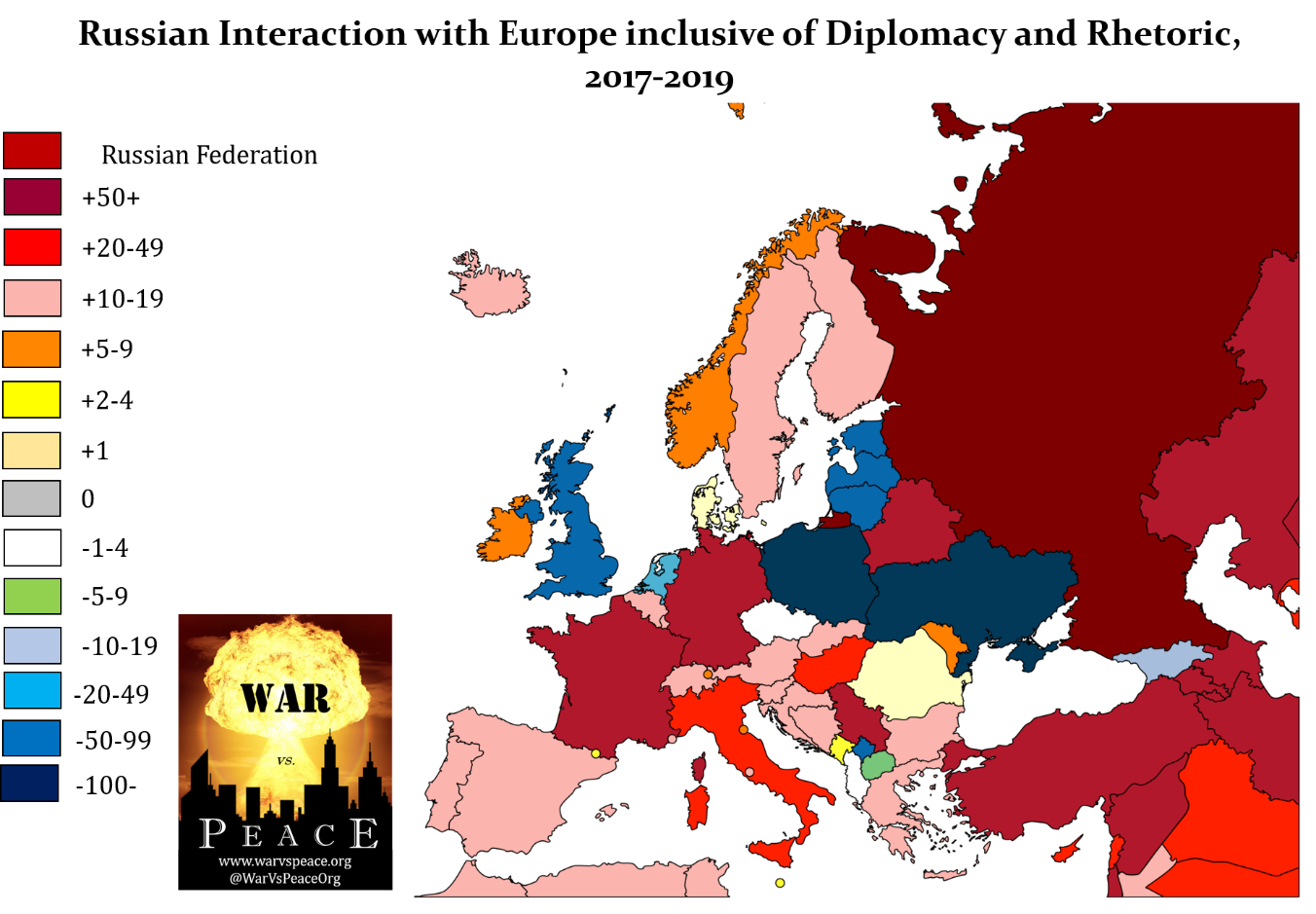

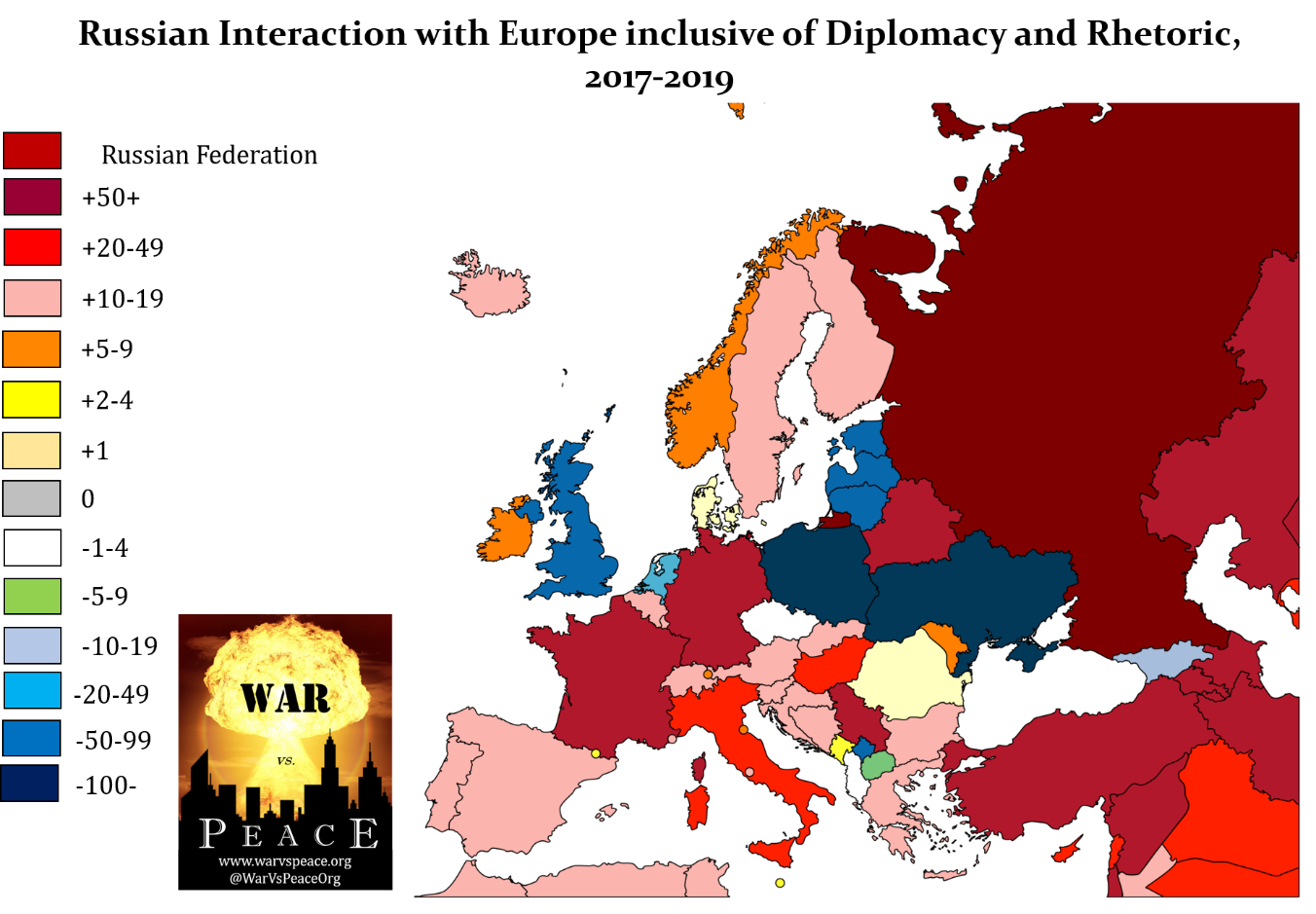

Before assuming that Map 1 represents the future battle lines of Europe, however, it must be noted that, despite the vitriolic rhetoric emanating from Moscow, Russian diplomatic engagement with Europe goes on. Much of this pertains to Russian actions in the Middle East, especially in Syria, but it also reflects the enduring bilateral relationships of much of Europe with Russia, regardless of the ongoing disputes over Ukraine. If one combines the frequency of these meetings, the rhetoric of Moscow, and the frequency of signing bilateral agreements (e.g. protocols for state meetings, visa-free travel, etc.) and exacting punishments (e.g. new sanctions, summoning the ambassador, etc.), Europe appears more as Map 2.

The latter map suggests that, in the event of a military confrontation with the West, Russia may yet be able to divide and conquer the NATO alliance, especially if the US remains lukewarm toward maintaining Transatlantic solidarity and cohesion. The map also clearly indicates that potential conflict is most highly anticipated in the Intermarium countries directly on Russia’s borders. Perhaps ironically, this divide follows roughly the cordon sanitaire of the interwar (1918–1939) years. Both maps indicate Poland and Ukraine as the center of Russia’s ire in the West, complemented by the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Georgia and Kosovo. Less problematic states include Albania, Czechia (the Czech Republic), Denmark, North Macedonia and Romania. This suggests that Russian defensive and counteroffensive planning for the Europe-facing strategic direction revolves around defeating the militaries of Ukraine and the countries on NATO’s northeastern (Baltic) flank.

Another indication of Moscow’s strategic focus on these countries is the frequency of articles written on their present-day military-political situations in the Russian press. Out of just under 500 articles surveyed in 2019,[9] 141 examined the changing dynamic in Europe. Of those 141, 94 (two-thirds) considered Poland, Ukraine, Belarus or the Baltic States specifically. Map 2. Russian Interaction with Europe inclusive of Diplomacy and Rhetoric, 2017–2019

Map 2. Russian Interaction with Europe inclusive of Diplomacy and Rhetoric, 2017–2019

Map 2. Russian Interaction with Europe inclusive of Diplomacy and Rhetoric, 2017–2019

Map 2. Russian Interaction with Europe inclusive of Diplomacy and Rhetoric, 2017–2019

Russian military planning in Europe therefore appears to concern itself primarily with these six countries in addition to NATO allies most likely to intervene on their behalf, especially the United States, United Kingdom and Canada.[10] Georgia boasts increased cooperation with NATO but lies outside the European strategic direction, while Kosovo represents a different potential challenge than those countries on Russia’s doorstep.

Notable from both above-presented maps is the unique role in Europe played by Belarus. Each one indicates that Moscow regards Belarus as a critical continental partner. However, unlike other major perceived partners France and Germany, Belarus is not considered an “important country” in Moscow. This is quantitatively demonstrated in Map 3, which tallies the number of separate deputy foreign ministerial interactions Moscow has conducted with each European capital throughout 2019. This metric is inherently illustrative because Moscow generally assigns only one deputy foreign minister to each region in addition to several responsible for specific diplomatic projects such as arms control. Thus, Moscow indirectly demonstrates the importance it attributes to foreign governments by whether it is worth dispatching deputy foreign ministers irrelevant to bilateral relations to better understand that government’s broader foreign policy.[11] Map 3 indicates that whereas Russian partnerships with France, Germany and Turkey are based at least in part on Paris’, Berlin’s and Ankara’s perceived importance, neither Minsk nor Belgrade receive this respect despite the sentiments displayed in Map 2.

Belarus’s geographic position between Russia and its perceived opponents in Central and Eastern Europe makes it a critical component of regional Russian military contingency planning, as will be shown below. However, Map 3 suggests that Minsk’s own policies are frequently ignored in Moscow and have little bearing on Russia’s foreign or defense policy calculations. This reveals a potential weakness in Russian military and strategic planning if Minsk objects to Russian use of force against Europe from Belarusian territory.[12] Map 3. Number of Russian Deputy Foreign Ministers Consulting Each Country in Europe, 2019

Map 3. Number of Russian Deputy Foreign Ministers Consulting Each Country in Europe, 2019

Map 3. Number of Russian Deputy Foreign Ministers Consulting Each Country in Europe, 2019

Map 3. Number of Russian Deputy Foreign Ministers Consulting Each Country in Europe, 2019

Western High Command Training Patterns

The author does not consider overt Russian aggression against NATO members in Central and Eastern Europe probable. Indeed, such a scenario seems almost implausible given the North Atlantic Alliance’s vastly superior overall military capabilities, despite the demographic-driven weakness of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania and an unfavorable (toward NATO) balance of forces within the Baltic region itself. This paper, therefore, assumes that Russian military contingencies in Europe involve Moscow perceiving its neighbors to be actively destabilizing either the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave, other Russian territories or Russian political society at large. A hypothetical example may be Poland, Lithuania and Latvia blocking the resupply of materials to Kaliningrad Oblast during anti-Kremlin civic disorder in the region. Yet, even in that circumstance, Russia would probably attempt to resolve the crisis by maritime and air lines of communication before resorting to armed force; the most likely instigation for war would be a NATO member’s use of force to support anti-Kremlin protesters, another improbable prospect, albeit one feared in Moscow and Minsk. The Zapad 2017 strategic-operational exercise scenario involved expunging Western special forces support for anti-government forces.[13] Belarusian President Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s military response to protesters after the disputed 2020 presidential election seems to follow this pattern,[14] suggesting the president’s suspicion of the West’s presence among his opponents.

It is also important to note that the Russian Western High Command (ZGK) does not consider the five aforementioned “problematic” border states—Ukraine, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania—to form part of a single strategic direction. Rather, the ZGK plans along three strategic directions roughly analogous to the late Soviet teatr voennykh destvii (TVD) borders: northwestern, western and southwestern. The northwestern strategic direction encompasses the Baltic region, including Polish coastal areas. The western strategic direction primarily pertains to Poland and Belarus. The southwestern strategic direction includes Ukraine and the Balkans. As in the Soviet era, these regions include some territorial overlap. Belarus, Russia’s only ally in the region, also divides its forces between two strategic directions—northwest and west—seemingly contiguous with Russia’s definitions.

Though Russia could attempt operations along multiple of these strategic directions simultaneously, this would be a risky gamble. The ZGK’s strategic and strategic-operational exercises of recent years have each focused on an individual strategic direction at a time, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Russian Strategic and Strategic-Operational Exercises in the West

Exercise Strategic Direction

Zapad 2009 (West 2009) Western

Zapad 2013 (West 2013) Western

Shchit Soyuza 2015 (Union Shield 2015) Northwestern

Zapad 2017 (West 2017) Northwestern

Shchit Soyuza 2019 (Union Shield 2019) Northwestern

Belarus participated in each of those exercises, perhaps explaining why there has not yet been any focus on the southwestern strategic direction. At the very least, it suggests Belarus has made no overt contingency plans for attacking Ukraine with its own forces. To date, the war in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas appears to be managed from Rostov Oblast, under the auspices of Russia’s Southern High Command.

Understanding Russian military planning in Europe requires a greater depth of examination of the units available to the ZGK as well as how they train. The strategic and strategic-operational exercises listed above are merely capstone events of training cycles rather than displays of all capabilities.

The Western High Command’s Evolving Order of Battle

In Russian military parlance, a high command (glavnoe kommandovanie) is the staff commanding forces within a TVD or strategic direction.[15] A military district (voenniy okrug) is responsible for training and arming units in peacetime so that they are at maximum readiness for the demands of the high command in the event of war.[16] The ZGK is responsible for potential warfighting, but the Western Military District (ZVO) supplies only the core of the force that the ZGK would command.

The Western Military District

The ZVO is comprised of three armies, one air force and air-defense army, three airborne divisions, one airborne brigade, the Baltic Fleet, and an army corps attached to the Baltic Fleet.

– Ground Forces. The ZVO’s three armies fall neatly into the three strategic directions on a map, if less so in practice. The 6th Combined Arms Army is based around St. Petersburg, in the northwestern strategic direction; the 1st Guards Tank Army is around Moscow, in the western strategic direction; and the 20th Guards Combined Arms Army is based between Smolensk and Voronezh, in the southwestern strategic direction. The 11th Army Corps, formally attached to the Baltic Fleet, is based in the Kaliningrad Oblast exclave. These units’ paper-strength capabilities are not comparable, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. ZVO Ground Forces Unit Breakdown

Army (Corps) Tank Units Motor Rifle Artillery Units Engineer Units Attack Helo Units Units*

1st Guards 1 Division, 1 Division, 2 ARTY Brigades, 3 Brigades,

Tank Army 1 Brigade 1 Brigade 1 Missile Brigade, 1 Regiment, 1 Brigade

1 Thermobaric BAT 1 LOG BGE,1 Rail BGE

2 ARTY Brigades, 1 Regiment,

6th Army N/A 2 Brigades 1 Missile Brigade, 1 LOG BGE, 2 Brigades

1 Thermobaric BAT 1 Rail BGE

1 ARTY Brigade, 1 Regiment,

20th Guards 1 Brigade 2 Divisions 1 Missile Brigade 1 LOG BGE, N/A

Army 1 Rail BGE

1 Brigade, 1 ARTY Brigade, 1 Regiment,

11th Army 1 REG 1 Regiment, 1 Missile Brigade 2 Battalions 2 Battalions

Corps 1 Marine BGE

*Attack helicopter units are technically part of the Air Force and Air Defense Army

*Attack helicopter units are technically part of the Air Force and Air Defense Army

Immediately notable is the far greater strength of the 1st Guards Tank Army compared to the others, though the 20th Guards Army is still not fully organized and may yet acquire additional forces. Another key specialization visible is that whereas the 1st Guards Tank Army possesses by far the most tanks, the 6th Army has the most attack helicopters. This suggests that the different units are expected to fight in different regions.

– Airborne Troops. The Airborne Troops (VDV) form a separate branch of the Russian Armed Forces. Though they follow their own training regimen and frequently exercise separately from the other services in the strategic exercises, they appear also to conform to the strategic directions based on their peacetime garrisons.

Table 3. Distribution of ZVO VDV Units by Strategic Direction

Northwestern 1 Division

Western 2 Divisions

Southwestern 1 Brigade

– Aerospace Forces. The Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) combine combat aviation, air defense, and space-based capabilities. In the ZVO, this is organized into the 6th Air Force and Air Defense Army. This is augmented by a separate 15th Army responsible specifically for the air and missile defense of Moscow, but this unit is extremely unlikely to deploy away from the capital under any circumstances. The 6th Air Force and Air Defense Army frequently exercises moving its assets across ZVO territory but garrisons those assets in several bases analogous to the strategic directions. However, it should be assumed that in wartime, all these assets would be redirected as necessary to any of the three strategic directions.

Table 4. Distribution of ZVO VKS Units by Strategic Direction in Peacetime

Strategic Direction Fighter Units Strike Units Reconnaissance Units Air Defense Units

Northwestern 2 Regiments N/A N/A 1 Division

Western N/A N/A 1 Regiment 1 Division

Southwestern 1 Regiment 1 Regiment N/A N/A

Kaliningrad* 1 Regiment 1 Regiment N/A 1 Division

*Kaliningrad’s aviation assets are technically naval aviation but infrequently exercise as such.

– Navy. The ZVO possesses the Baltic Fleet, based out of Baltiysk, Kaliningrad Oblast, and Kronshtadt, St. Petersburg, though most assets are garrisoned in the former. While it possesses a decent number of ships, the Baltic Fleet generally keeps most of them at port. To illustrate this, Table 5 displays how many ships the Baltic Fleet possesses that have conducted an exercise at least once over the past three years arranged into how many training activities they have publicly reported in 2019.

Table 5. Baltic Fleet Assets by Number of Reported Exercises in 2019

Exercise Destroyers Frigates Corvettes Amphibious Minesweepers Other Submarines

Count Ships Support

10+ 1 5

5–9 7 3

1–4 1 8 8 5 4 1

0 1 1 3 2 4

Total 1 2 21 14 7 8 1

As can be observed, the emphasized capability in the Baltic Fleet are the corvettes or small missile ships. These ships are specially equipped to offer distributed lethality against all targets—including shore and missiles.

Neighboring Military Districts

The ZGK can be augmented by assets outside the ZVO in wartime. Although most units could conceivably be redeployed in that manner, this paper will only list the most likely sources of reinforcement and their potential roles in the European strategic directions.

– Joint Strategic Command “North.” The Arctic-focused Northern strategic command was detached from the ZGK and ZVO only in 2014 and features Russia’s most powerful, if aging, Northern Fleet with considerable subsurface assets. This force would almost certainly augment operations in the northwestern strategic direction as well as provide medium- to long-range sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM) support from the Arctic. The Northern Fleet could also attempt to penetrate the so-called Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom (GIUK) gap to provide a wider range of missile targets, though such an operation would imperil the fleet’s survival given the large number of NATO naval aviation assets around the North Sea. The ground and air assets in the North would likely engage Norway in wartime if the latter joined NATO’s defense, but these assets would be extremely unlikely to deploy to another strategic direction given Russia’s self-perceived vulnerabilities in the Arctic.[17]

– Central Military District. The Central Military District (TsVO) encompasses a vast swathe of Russian territory, from the Volga region to eastern Siberia, with only two armies. Its air assets have recently been modernized (see below) and its ground forces are specialized for deployment, so it could augment the ZGK, though this would leave central Russia virtually undefended. TsVO air assets and its 2nd Guards Army would likely move forward to augment Russian defenses wherever the ZVO’s deployed forces departed. For example, during the northwestern-focused Zapad 2017, the 2nd Guards Army deployed some forces to Karelia and Murmansk Oblasts opposite the Finnish border.[18] This probably was intended to absorb a hypothetical NATO attack on St. Petersburg or a Finnish counteroffensive honoring bilateral ties with Estonia.[19] In an extended conflict, these assets could also form a subsequent echelon of a Russian offensive.

– Southern Military District. The Southern Military District (YuVO) faces the Caucasus, Black Sea and Caspian Sea, and it has coordinated the military activities in Crimea and Donbas against Ukraine since 2014. However, whereas its assets would play a critical role in a southwestern strategic direction campaign, it appears that the impetus for creating the current 20th Guards Army since 2015 has been to reduce the demands of Ukraine on YuVO assets. As in the Second World War, the YuVO’s 8th Guards Army might deliberately fix Ukrainian assets in Donbas while the ZVO’s 20th Guards Army assaulted Kyiv directly. However, this would likely be the only scenario employing YuVO assets in Europe. Though the Baltic Fleet regularly exercises sending assets to the Mediterranean Sea and sometimes the Black Sea, the Black Sea Fleet has made no similar effort to the Baltic Sea in recent years, though this may simply be a product of the current military-political situation.

– Non-District Forces. Russia also possesses several assets unattached to a particular military district, including Long-Range Aviation, Strategic Rocket Forces, and some special airborne troops. During wartime, the Strategic Rocket Forces would prepare for strategic nuclear exchange if the war escalated out of control. However, Long-Range Aviation and the other special airborne troops would provide additional strike and disruption capabilities wherever the ZGK required them, as was, indeed, exercised in Zapad 2017.[20]

Recent Military Modernization

Since Zapad 2017, of 1,589 incidents reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense of new capabilities delivered to the Armed Forces or unit restructurings or standups, 222 (14 percent) have been reported in the ZVO. Table 6 indicates that, after a surge at the end of 2017, the recent focus of Russian military modernization has been in the TsVO. Table 7 breaks down deliveries of new equipment within the ZVO, showing that the 6th and 20th guards armies have received the most attention. However, the absence of any disproportionate spike suggests that these trends show no significant realignment of priorities within the Russian General Staff or Ministry of Defense leadership on priorities among the three European strategic directions.

No comments:

Post a Comment