Chilamkuri Raja Mohan

As China and Pakistan deepen their strategic alliance and intensify their coordination on the Kashmir question and other regional issues, India’s relations with its two most important neighbours are likely to become more challenging now than before. The larger geopolitical churn among the major powers and the regional environment further complicates this challenge.

Introduction

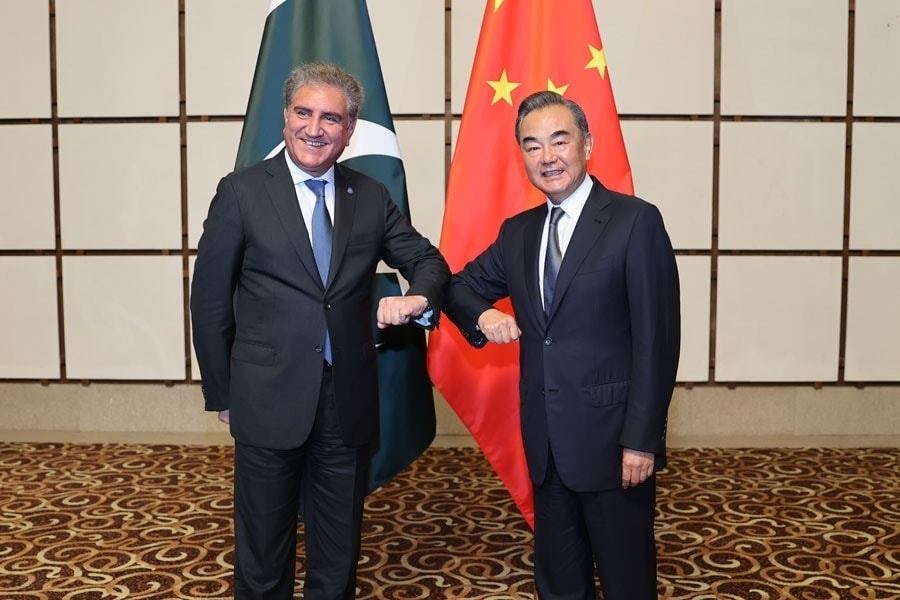

The second round of the strategic dialogue between China and Pakistan, led by foreign ministers Wang Yi and Shah Mahmood Qureshi in August 2020 in the Hainan province, did not produce any significant new initiatives. The focus was on the further consolidation of the all-weather partnership between Islamabad and Beijing across a broadening range of issues.

What makes this round of Sino-Pak strategic dialogue significant is the rapid deterioration of the India-China ties amidst the unresolved military standoff in eastern Ladakh. Coupled with the turbulence in the Middle East and the Indian Ocean, where China’s stakes are rapidly rising, and the sharpening contradictions between Beijing and Washington, the subcontinent’s geopolitical environment has arrived at a moment of discontinuity.

India has had to cope with the consequences of China-Pak partnership that can be traced back to the mid-1950s. Yet, Delhi has continuously underestimated the deepest sources animating it and possibilities for an ever-wider collaboration between Islamabad and Beijing. To make matters worse, Delhi has always over-determined the prospects for its own partnership with China and its ability to transcend the Sino-Pak alliance. However, the new dynamic of collaboration between its two troublesome neighbours makes it harder for Delhi to downplay it.

Kashmir Coordination

For India, the immediate concern is about intensive Sino-Pak political coordination on Kashmir. China has lent strong support to Islamabad’s efforts to mobilise international condemnation of Delhi’s constitutional changes in Kashmir since August 2019. The joint statement issued after the talks between Wang and Qureshi saw China reaffirm its criticism of India’s “unilateral actions” in Kashmir, in a reference to India’s decision to change the constitutional provisions relating to the state of Jammu and Kashmir, bifurcating the province into two Union Territories. No. 805 – 24 August 2020 2

“The Pakistani side briefed the Chinese side on the situation in Jammu and Kashmir, including its concerns, position and current urgent issues. The Chinese side reiterated that the Kashmir issue is a dispute left over from history between India and Pakistan, which is an objective fact, and that the dispute should be resolved peacefully and properly through the United Nations Charter, relevant Security Council resolutions and bilateral agreements. China opposes any unilateral actions that complicate the situation”, the statement said. In India, Delhi was quick to reject the references to Kashmir as an unwarranted interference in India’s internal affairs.

Iron Brothers

Delhi, of course, notes the expression of solid commitment from China and Pakistan to support the “core national interests” of the other. While China underlined its support for Pakistan’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, Islamabad expressed support for Beijing’s controversial policies against the majority Muslim community in Beijing’s far western province of Xinjiang.

The point here is not about Pakistan’s double standards in raising human rights concerns about Muslims in Kashmir but supporting China in Xinjiang. Hypocrisy is very much part of international life; neither Islamabad nor Beijing have a monopoly on this. The real story is about the deep foundations of the Sino-Pak alliance that transcends religion and is tied to shared interests of the two nations in containing India. In the joint statement, China described Pakistan as its “iron brother” and called Islamabad its “staunchest partner” in the region. India, however, has been reluctant to confront this central reality – which continues to express itself in multiple ways.

These range from the construction of the Karakoram Highway through Kashmir in the 1970s to the expansive China-Pakistan Economic Corridor of the present and from Beijing’s nuclear and missile assistance to Pakistan in the 1980s to the integration of Pakistani naval forces and bases into China’s ambitious Indian Ocean strategy.

Even as it fends off their coordinated attempt to put India in the international dock on Kashmir, Delhi must prepare for a full range of other contingencies that might allow for a joint probing of India’s other internal, regional and international vulnerabilities.

Geopolitical Churn

Even more important are the growing convergence of regional geopolitical interests between China and Pakistan. As China’s conflict with the United States (US) becomes sharper, Beijing is looking for reliable friends and partners on its periphery. Pakistan, which once served as a bridge between the US and China, is now viewed with much special importance in Beijing today.

Two reasons stand out. One is the growing strategic warmth between Delhi and Washington. China is viewing India’s foreign policy with increasing suspicion and is, therefore, more motivated than before to contain India’s rise. Delhi, however, is compelled to turn to the US as Beijing turns more assertive on the border disputes and undermines India’s regional primacy in the subcontinent. Pakistan, which has enjoyed much closer relations with the US than India ever did, is also concerned about the India-US strategic bonhomie. As its relations with the US and the West enter an indifferent phase, Pakistan’s need for Chinese support has grown considerably.

Second, is Pakistan’s role as an important Islamic nation, its location close to the Persian Gulf and its capacity for shaping the internal dynamics in Afghanistan. China values all these geopolitical attributes of Pakistan as Beijing raises its profile in the Afghan peace process, seeks to influence the outcomes in the Gulf and strengthen its position in the Islamic world. The manner in which these two sets of issues play out is bound to be complex. The quadrangular dynamic between the US, China, India and Pakistan will be sensitive to political and policy changes in all four nations. Meanwhile, Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf are likely enter a period of significant turbulence midst the speculation of US retrenchment, increasing the conflictual dynamic between India and the Sino-Pak alliance.

Professor C Raja Mohan is Director at the Institute of South Asian Studies (ISAS), an autonomous research institute at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He can be contacted at isascrm@nus.edu.sg. The author bears full responsibility for the facts cited and opinions expressed in this paper.

No comments:

Post a Comment