JAMES LAURENCESON

When Canberra called for an international, independent inquiry into Covid-19 in April, Beijing deployed trade restrictions measures against Australian beef and barley the next month.

When Canberra called for an international, independent inquiry into Covid-19 in April, Beijing deployed trade restrictions measures against Australian beef and barley the next month.

And so when the Australian government responded firmly to China imposing a sweeping national security law in Hong Kong at the end of June, the Australian Financial Review’s Andrew Tillett and Mike Smith wrote that “the government [was] privately bracing for a trade backlash as punishment”.

Sure enough, what followed was an anti-dumping investigation into Australian wine, another meat processor having its certification to supply the Chinese market suspended, and barley exports from a major Perth-based grain company barred on food safety grounds.

Trade minister Simon Birmingham says that “Australia is certainly not engaging in any type of trade war [with China]”. The Perth USAsia Centre’s Jeff Wilson concurred to the extent it was more a one-way “trade bashing”.

Yet Weihuan Zhou of the University of New South Wales also observes that “Australia itself has been one of the most frequent users of anti-dumping measures, particularly against China”.

And after watching Treasurer Josh Frydenberg block the sale of a dairy and drinks manufacturer from a Japanese owner to a Chinese one last month – despite the deal having the approval of the Foreign Investment Review Board and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission – the Australian National University’s Jane Golley assessed, “We’re on the verge of a trade and investment war – if we’re not already in one”.

While today’s situation is dire, there are still a few data points that suggest not all is lost.

The background is a deteriorating political relationship since at least 2017. Yet despite that, two-way trade has continued to grow.

In 2017, Australia’s exports to China were worth $116.0 billion, accounting for 30% of the total. By 2019, they had reached $169.1 billion, a 34.3% share.

And while the headlines this year have gravitated to instances increasingly appearing as Chinese trade punishment, in the first seven months of 2020 the total value of Australia’s goods exports to China is steady on the same period a year earlier. This is during a period in which much of the global economy has been in deep recession.

True, driving these aggregate numbers has been unexpectedly strong Chinese demand for iron ore. But this is not the only factor: wine sales to China over the past year inched upwards, too.

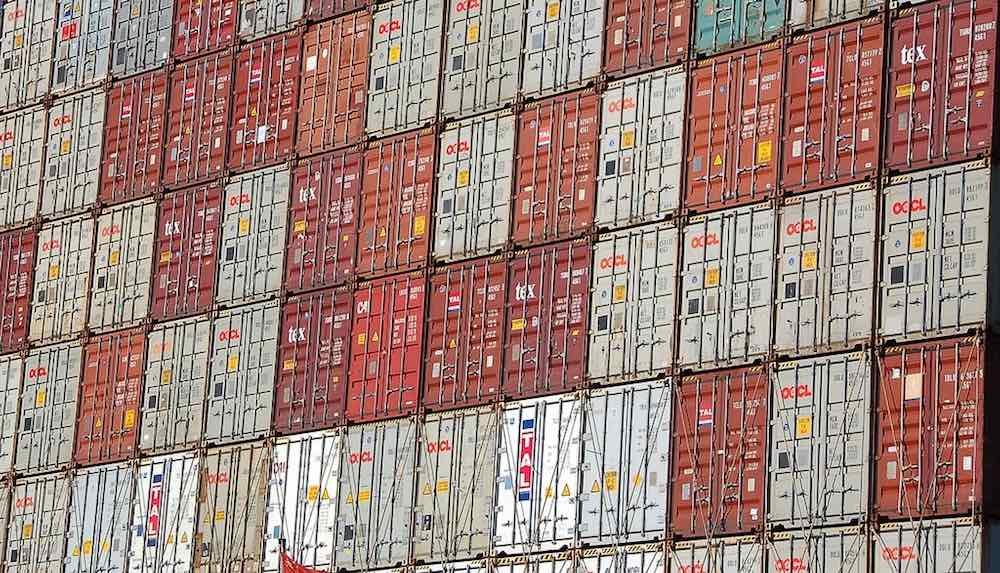

The Port of Melbourne (Chris Phutully/Flickr)

The Port of Melbourne (Chris Phutully/Flickr)

It is also within China’s capability to inflict far worse economic damage. Indeed, it appears to be choosing actions designed to limit the impact.

When four Australian meat processors had their certification suspended in May, Chinese customs still accepted shipments that were already in transit. And the measures left another seven plants continuing to sell chilled beef to China as normal. A further 20 or so are also able to sell the frozen product, which accounts for around 85% of all Australian beef exports to China by volume.

The barley story is different because prohibitive tariffs wiped out the trade. But these measures followed an 18-month Chinese anti-dumping investigation that gave Australian grain growers the opportunity to switch to other crops and seek out alternative markets. Many did precisely that.

The fact is that resisting aggressive Chinese moves is a domestic political winner for the Morrison government.

Of course, China is not exercising restraint out of benevolence. Trade is, by definition, a win-win exchange. So stopping trade means China loses too. Beijing could delist all Australian meat processors. But where would Chinese consumers get their high-quality meat protein from then?

Nor are Australian producers always without market power. In recent months, China has slipped to being Australia’s fourth-largest beef market, with the US, Japan and Korea leapfrogging it to consume the balance.

Perhaps Beijing’s calculations are even more simple: deep down it knows trade tantrums won’t work, so what’s the point in trying too hard?

The fact is that resisting aggressive Chinese moves is a domestic political winner for the Morrison government, and nowadays even the voices of groups with interests in urging moderation in Australian government policies, such as the business sector, have grown quieter.

China’s actions to date are also being beamed around the world, casting significant global doubt on its reputation as a reliable trading partner that plays by the rules. In July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo took pleasure in declaring that “the United States commends the Morrison government for standing up for democratic values and the rule of law, despite intense, continued, coercive pressure from the Chinese Communist Party to bow to Beijing’s wishes”.

None of this to suggest that Australia can afford to be complacent or arrogant. The costs of trade disruptions imposed by China are real, especially on individual Australian companies and specific regions, even if they are not as large as commonly imagined.

And “own goals” ought to be avoided.

Australia’s agricultural sector has fair reason to be disappointed by inexplicable decisions made in Canberra around foreign investment.

There is also a difference between making considered statements that defend Australian interests and megaphone diplomacy. Last week, former foreign affairs minister Julie Bishop said, “In my experience, it is possible to have robust private discussions with Chinese officials about all aspects of the relationship … They react badly when such discussions are in the public domain, particularly if such matters were not first raised in confidence.”

The ability to de-escalate remains within the capacity of both Canberra and Beijing, and once again allows Australia and Chinese companies and households get on with the engagement that both sides agree is of mutual benefit.

No comments:

Post a Comment