Vinay Kaura

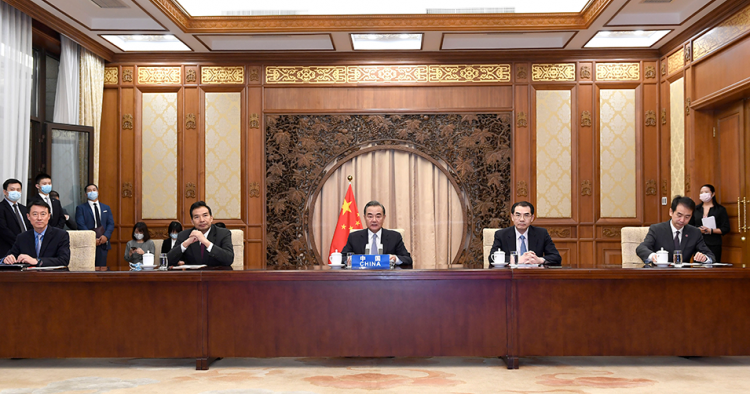

On July 27, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a video conference with his counterparts from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal to suggest expanding their pandemic cooperation. Stressing the need to set up a logistics “green corridor” to expedite customs clearance between their countries, Wang also proposed the development of a multimodal trans-Himalayan corridor by extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan, and he took the opportunity to call on Nepal and Afghanistan to follow the example of Sino-Pakistan cooperation.

On July 27, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a video conference with his counterparts from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal to suggest expanding their pandemic cooperation. Stressing the need to set up a logistics “green corridor” to expedite customs clearance between their countries, Wang also proposed the development of a multimodal trans-Himalayan corridor by extending the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) into Afghanistan, and he took the opportunity to call on Nepal and Afghanistan to follow the example of Sino-Pakistan cooperation.

This meeting should make policymakers in Washington and New Delhi sit up and take notice of potential regional realignments. Although the details about what this quadrilateral framework would entail and how it would work are unclear, any movement toward its institutionalization would be a serious challenge for the United States. In the aftermath of a U.S. departure from Afghanistan, any Chinese attempt to integrate landlocked Afghanistan and Nepal into the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s international infrastructure development program, would directly undermine both America and India’s geopolitical interests.

Analyzing recent speeches by top American officials, Anthony H. Cordesman has argued that America’s approach toward China has shifted from a mixture of competition and cooperation to direct confrontation. The bipartisan consensus that the U.S. should support China is being replaced with an equally strong distrust of China’s geo-economic and geopolitical motives. As the relationship between the two countries has assumed an increasingly antagonistic dimension, the consequences will likely be wide-ranging, including for Afghanistan.

Security and diplomatic cooperation and coordination between India and the U.S. has been on the rise in recent years, particularly since Donald Trump became president. Consistent with American activism, India has been gradually shedding its long-held hesitation about being a pro-active participant in militarizing its alliance with the U.S., Japan, and Australia against China’s increasingly aggressive expansion in the Indo-Pacific region. Both Washington and New Delhi characterize the BRI as a “debt trap,” much to China’s annoyance. Much of India’s developmental and diplomatic footprint in Afghanistan has been possible due to America’s military presence. Therefore, if Kabul agrees to Beijing’s proposal to extend the CPEC into Afghanistan, it would directly challenge New Delhi’s plans to increase its own footprint there.

Growing US-China rivalry

The dynamics of strategic rivalry between America and China are starting to play a dominant role in Beijing’s calculations. However, the U.S. is not oblivious to China’s attempt to shift the regional balance of power in its favor. Alice Wells, the recently retired acting assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asia, had criticized China’s role in Afghanistan in November 2019. Speaking at the Wilson Center, Wells said, “China has not been a real player in Afghanistan development. … I haven’t seen China take the steps that would make it a real contributor to Afghanistan’s stabilization, much less stitching it back into Central Asia and the international community.” In late June and early July, the U.S. special envoy to Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad, accompanied for the first time by Adam Boehler, CEO of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, visited Doha, Islamabad, and Tashkent to hold a series of meetings with the foreign ministers of Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the five Central Asian republics. They also met with the Afghan Taliban negotiators based in Qatar. The primary objective of their regional tour was to convey America’s determination to remain geopolitically invested in Afghanistan, even after U.S. troops are withdrawn in line with the February 2020 deal with the Taliban.

Since 2001, Afghanistan has dominated America’s approach toward Central Asia. In February 2020, the Trump administration unveiled a new policy document, the “United States Strategy for Central Asia 2019-2025: Advancing Sovereignty and Economic Prosperity,” which draws clear linkages between America’s Central Asia policy and the evolving situation in Afghanistan. This is reflected in the assertion that the “United States recognizes that a secure and stable Afghanistan is a top priority for the Central Asian governments, and each has an important role to play in supporting a peace process that will end the conflict. … The Central Asian states will develop closer ties with Afghanistan across energy, economic, cultural, trade, and security lines that directly contribute to regional stability.”

Since Washington views Central Asia primarily through the lens of Afghanistan, the U.S. is most likely to caution Central Asian states with regards to their relations with China. By contrast, China views Central Asia as a buffer against Uighur militancy in Xinjiang, where Beijing’s heavy-handed policies against Muslim minorities have attracted widespread global censure. Seen in these contexts, it should be no surprise if Beijing attempts to reactivate the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism (QCCM), whereby China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan seek to cooperate with Tajikistan on counterterrorism and cross-border militant infiltration. Significantly, Russia is not part of the QCCM.

Previously, China was not hostile to good ties between the U.S. and Pakistan as Beijing saw such engagement as having many economic and security advantages for Pakistan, particularly as it seeks to balance India in the region. In turn, America was neutral about China’s economic activities in Pakistan, as Beijing’s commercial investments were seen as promoting economic growth. In fact, coinciding with the Obama administration’s plan to reduce the U.S. military footprint in Afghanistan, Washington even encouraged China to expand its regional activities in the war-torn country. After winning a bitterly contested and controversial presidential election, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani chose to visit Beijing in October 2014 for his first overseas trip, rather than Washington or New Delhi. Beijing reciprocated by hosting talks in May 2015 between the Afghan government and the Afghan Taliban in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang Province. Although these talks eventually faltered, China’s initiatives led to subsequent dialogues in many different formats, one of which included the U.S. as well. All of this seems to have become history though, as the perception on both sides has changed dramatically in the years since.

Ties with the Taliban

China’s engagement with the Taliban has come a long way since Beijing first came into contact with the insurgent group in the 1990s to protect its interests. Initially, China was worried by the Taliban’s close ties with the anti-Chinese terrorist group, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which operated militant camps in Afghanistan. However, many factors paved the way for Beijing to improve its ties with the Taliban when it came to power. According to a Pakistani senator, China’s ambassador to Pakistan, Lu Shulin, held a meeting with Mullah Omar, the supreme Taliban leader, in Kandahar in December 2000.

Since 2001, China has been hedging its bets, maintaining formal ties with the Kabul regime and informal ones with the Taliban. As it is not a primary party to the Afghan conflict, China has been flexible in its policies, and Beijing has been involved in several multilateral initiatives to seek a political settlement between Kabul and the Taliban. There have also been many bilateral discussions, mostly secret, between Chinese officials and the Taliban in recent years. But in June 2019 Beijing publicly declared that it had hosted a Taliban delegation led by Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar. When President Donald Trump suddenly cancelled the talks with the Taliban in September 2019, China attempted to inject itself into the process by inviting the group to Beijing for a two-day intra-Afghan conference in October. However, the talks had to be postponed.

China’s major concern is that the continuing instability in Afghanistan could be exploited by Uighur militants and that the threat of terrorist spillover from Afghanistan could threaten massive Chinese-funded infrastructure projects in Pakistan and Central Asia. But the hypocrisy of China’s “good Muslim, bad Muslim” policy — oppressing all Muslim ethnic groups at home in the name of counterterrorism while engaging with the Taliban abroad — has never been in doubt. In fact, Beijing’s engagement with the Taliban mirrors Islamabad’s motives: appeasement to prevent attacks at home and installation of an Afghan government not friendly to either India or the U.S. China’s growing alignment with Pakistan to manage the Afghan problem can also be seen as a counterweight to Indo-U.S. coordination. Moreover, the Afghan government has also used Beijing to persuade Pakistan’s security establishment to deliver the Taliban to the negotiating table and to seek Chinese cooperation on economic development.

Rising tensions, uncomfortable choices

With rising tensions between the U.S. and China, Pakistan too faces uncomfortable choices and is not willing to be seen as taking sides. Islamabad prizes its relationship with Beijing, aware that China’s vociferous and public support is crucial to protecting it from being named and shamed for sponsoring terrorism in international forums, including the UN. The day after Khalilzad was in Islamabad, Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi spoke with Wang, and shortly thereafter Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan declared that the CPEC projects would be completed “at any cost.”

The trilateral dialogue between the foreign ministries of China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan has also been revived. After the last meeting in September 2019, the latest round was held online on July 7, with Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Luo Zhaohui, Afghan Deputy Foreign Minister Mirwais Nab, and Pakistani Foreign Secretary Sohail Mahmood participating. Soon after this virtual meet, Pakistan opened five key routes with Afghanistan for bilateral and transit trade.

At Pakistan’s invitation, Abdullah Abdullah, the head of Afghanistan’s High Council for National Reconciliation, is planning to visit Islamabad soon to reduce misunderstandings and mistrust. When he was Afghanistan’s CEO, Abdullah never visited Pakistan despite numerous invitations. Given that President Ghani continues to enjoy American and Indian support, it is reasonable to argue that by engaging Abdullah through Islamabad, China might be attempting to take advantage of the power struggle between the two men.

China has recently decided to proceed with a 25-year strategic cooperation agreement with Iran, a development the U.S. views as a threat to its predominant position in the Middle East. This agreement also envisages the export of Iranian energy to Gwadar port in Pakistan, whose military use by China has always been a strong possibility. The growing strategic alignment between China and Iran could also dampen India’s attempts to shore up connectivity to Afghanistan and Central Asia though Iran’s Chabahar port, where New Delhi has invested heavily. It is because of India’s insistence that this strategically located port has been spared from American sanctions against Iran because its operations are seen as serving reconstruction and development objectives in Afghanistan. That is why despite escalating tensions between Washington and Tehran, trade, commercial, and infrastructural activities at Chabahar port, particularly involving India, Afghanistan, and Iran, continue to enjoy immunity as its “strategic location makes it a kind of political Bermuda triangle, where the normal rules of the U.S.’s hostile Iran policy do not seem to apply.”

Beijing’s bid to widen its sphere of influence

China has aggressively stepped up its efforts to widen its sphere of influence, specifically along its periphery, through a relationship of dependence and subservience. Earlier, any significant multilateral effort aimed at accelerating the Afghan peace process had representation from America; however, the recent initiatives by China clearly indicate that Beijing’s aims vis-à-vis Afghanistan are moving in a starkly different direction than the one being followed by the U.S.

Beijing is likely to continue increasing its engagement with Afghanistan. For both Washington and New Delhi, however, increased Chinese presence in Afghanistan has the potential to undermine their fundamental objectives vis-à-vis Afghanistan: to eliminate terrorist infrastructure and reduce Pakistan’s influence over terrorist outfits in Afghanistan, and to utilize Afghanistan’s location to connect South Asia with Central Asia’s vast energy resources. Against this background, how China seeks to achieve its strategic aims in the absence of American troops on the ground, and the alliances it forges in the process, are likely to significantly influence the power dynamics in Afghanistan, both internally and externally.

Vinay Kaura, PhD, is a Non-Resident Scholar with MEI's Afghanistan & Pakistan Program, an Assistant Professor in the Department of International Affairs and Security Studies at the Sardar Patel University of Police, Security, and Criminal Justice in Rajasthan, and the Coordinator at the Center for Peace and Conflict Studies in Jaipur. The views expressed in this article are his own.

No comments:

Post a Comment