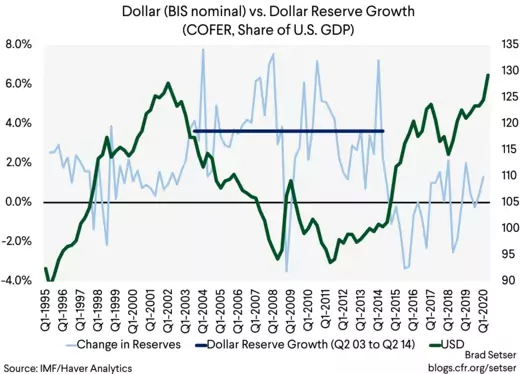

Large increases in dollar reserves tend to come during periods of dollar weakness, not periods of dollar strength. That is for a simple reason: many export-heavy countries still intervene heavily in the foreign currency market to try to keep their own currencies from appreciating against the dollar. Until Asia is as willing to float up as it is to float down, the dollar isn't going anywhere as a reserve currency.

The fall in the dollar this July (from a very high level after the dollar’s appreciation during the financial turmoil in March is no exception).

And to be honest, President Trump has done his share to raise concerns about the dollar’s position in the global financial system. Once unthinkable options sometimes apparently get considered.*

Just as the United States is thinking again about its supply chain vulnerability, China is thinking again about its financial vulnerability—as it still uses the dollar to denominate a decent amount of its trade and even the external lending of its state banks (the policy banks as well as the state commercial banks though China never has been willing to clearly specify the line dividing the two). And many Europeans—building on a long intellectual tradition in France—have been looking again to increase the euro’s global role. The long reach of U.S. sanctions on Iran no doubt has been a catalyst here too.

But there is another dynamic at play now as well—one that isn’t as well known as it should be.

A weaker dollar tends to lead to more intervention by countries looking to protect their exports in the foreign exchange market, and thus more reserve accumulation.

A weaker dollar thus typically results in higher not lower demand for dollars from the world’s reserve managers.

To be sure, the claim that the dollar is the world’s preeminent reserve currency is generally used in a broad sense of the currency used most frequently in international payments—not in the narrow sense of the currency used to denominate the world’s reserve assets. It is often used to mean that the dollar is the leading currency for invoicing global trade, and the vehicle currency needed to execute most foreign currency trades (if you have euros and want to buy Brazilian real, you—or your bank—might sell euros for dollars and then use the dollars to buy Brazilian real). Dollar assets are much more central to the retirement savings of the Asian surplus countries than say euro assets—the GPIF apparently has a ton of short-term Treasuries, Japan’s lifers have an enormous portfolio of long-term U.S. corporate bonds, and Taiwan’s life insurers have invested more funds in the U.S. dollar than in the Taiwan dollar (which is in fact a problem).

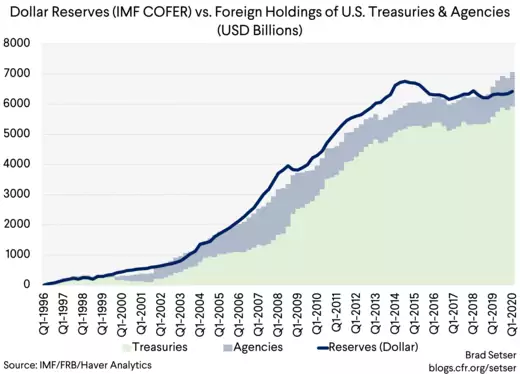

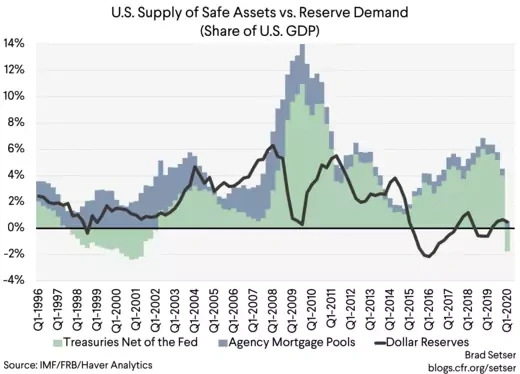

But the dollar’s role in global reserves is still important—the world’s holdings of dollar reserves are now something like 30 percent of U.S. GDP. Mechanically, those holdings—and the absence of any real holdings of foreign currency reserves by the United States—account for a large share of the United States’ net external debt position (and over time the U.S. external deficit has clearly been funded by selling debt not equity to the world, a fact that has only become more apparent over time).**

And one of the most regular patterns in the global economy is that dollar reserve holdings tend to go up when the dollar goes down.

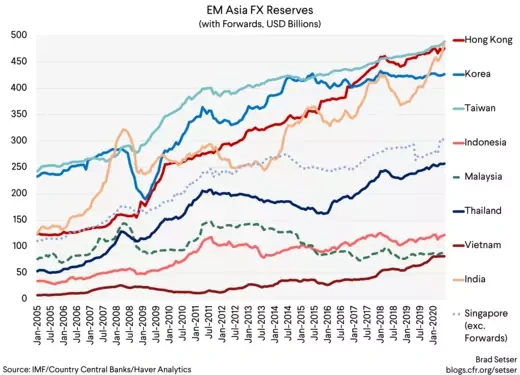

This should be obvious say from this chart.

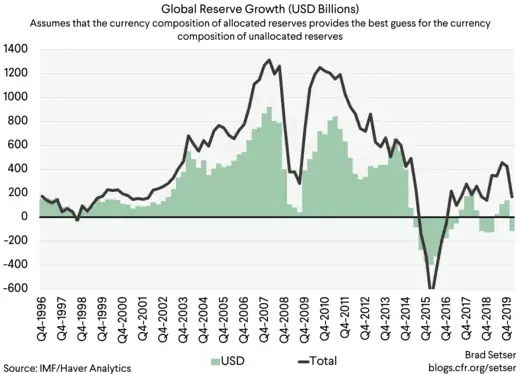

The reason for this is simple, and well known to those who follow certain parts of the foreign exchange market.

The dollar cannot depreciate unless another currency appreciates—and some export driven economies (especially export driven Asian economies) often do not want their currencies to appreciate.

To resist appreciation, they buy dollars for their reserves (or have other state directed institutions buy dollars—doing more or less the reverse of what Turkey’s state banks have been doing recently). That means that dollar weakness leads to faster global reserve growth, and higher global holdings of dollars among the world’s central banks.

So if you take the “reserve currency” meaning of the dollar literally, a weaker dollar tends to mean a rise in the world’s dollar reserve holdings.

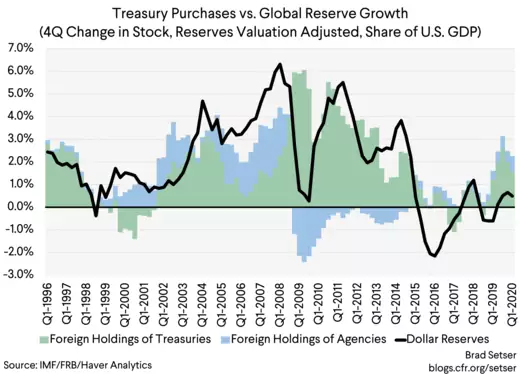

And thus more not less foreign demand for Treasuries, as most foreign demand for Treasuries still tends to come from official accounts.***

In fact, there are already signs that this is happening in the early data on foreign exchange reserve holdings for July (full data is available with a month’s lag, as many countries buy dollars in the foreign exchange market and then swap them for local currency as a sterilization tool—so intervention shows up in the forwards data at the end of the month).

Our updated tracker for currency manipulation suggests that three or four countries met the definition of manipulation through the first quarter (largely because of intervention at the turn of the year) and some of those countries have been back in the market in June and July. Thai reserves are up. Taiwan’s reserves really jumped in July, with anecdotal reports of heavy intervention. Singapore is intervening too (though that is hardly news if you know where to look). India as well, but its current account only recently moved into surplus so it isn’t at risk of being dinged for manipulation by the U.S. Treasury.

Now there are some secondary dynamics—dynamics that keep those who make their living watching foreign currency flows busy.

Asian intervention tends to be done in the spot market vis-à-vis the dollar (unlike Swiss intervention, which is done vs. the euro). So big dollar purchases in Asia tend to be followed by selling the dollar for euro to meet portfolio diversification targets (countries hold most of their reserves in dollars, but without some purchases of euros in the market, Asian countries that intervene against the dollar would hold all their reserves in dollars). That can add to the pressure pushing the euro up, fueling a cycle of intervention.****

But at the end of the day, this isn’t a complex story.

Many export-based economies with large external surpluses are willing to let their currency fall against the dollar, but they remain reluctant to let their currency appreciate against the dollar when the tide turns. And thus the bulk of the world’s accumulation of dollar reserves has tended to come when the market is pushing the dollar down not up.

* Not paying U.S. Treasury bonds to make China pay for the cost of the corona virus.

** The net equity position of the United States is now substantially negative in the net international investment position data, though this “reverse” exorbitant privilege hasn’t gotten as much academic attention as the “exorbitant” privilege exhibited when the dollar depreciated (raising the value of U.S. external assets) back in 05, 06, 07, and the first part of 08.

*** The safe asset shortage in the middle of the last decade had a simple cause in my view, one that doesn't get as much attention from academic economists as it should, namely that net issuance of Treasury bonds lagged the growth in demand for reserve assets from central banks intervening to hold their currency down (Central bank reserve accumulation doesn't tend to be central to most academic models of the global economy these days; market participants tend to pay more attention to reserve trends than economics departments).

**** For example, I now think central banks reallocating dollar purchases toward the euro was a significant factor behind the euro's strength in 07 and 08.

No comments:

Post a Comment